Women in love aren’t crazy in Joi Barrios’ romances

Back in the 1980s, Filipino teenagers read American “Sweet Dreams” romance novels, reeled in by the boy-meets-girl tropes and Cinderella endings. In Suzanne Rand’s “Green Eyes,” for example, square peg Julie Eaton and popular athlete Dan Buckley are a couple, but their relationship is threatened when Dan’s ex-girlfriend Pam Kershaw returns. Julie works herself into a frenzy of jealousy and self-doubt because she’s nondescript next to tall, slim and pretty Pam. But in the end, Julie and Dan reconcile.

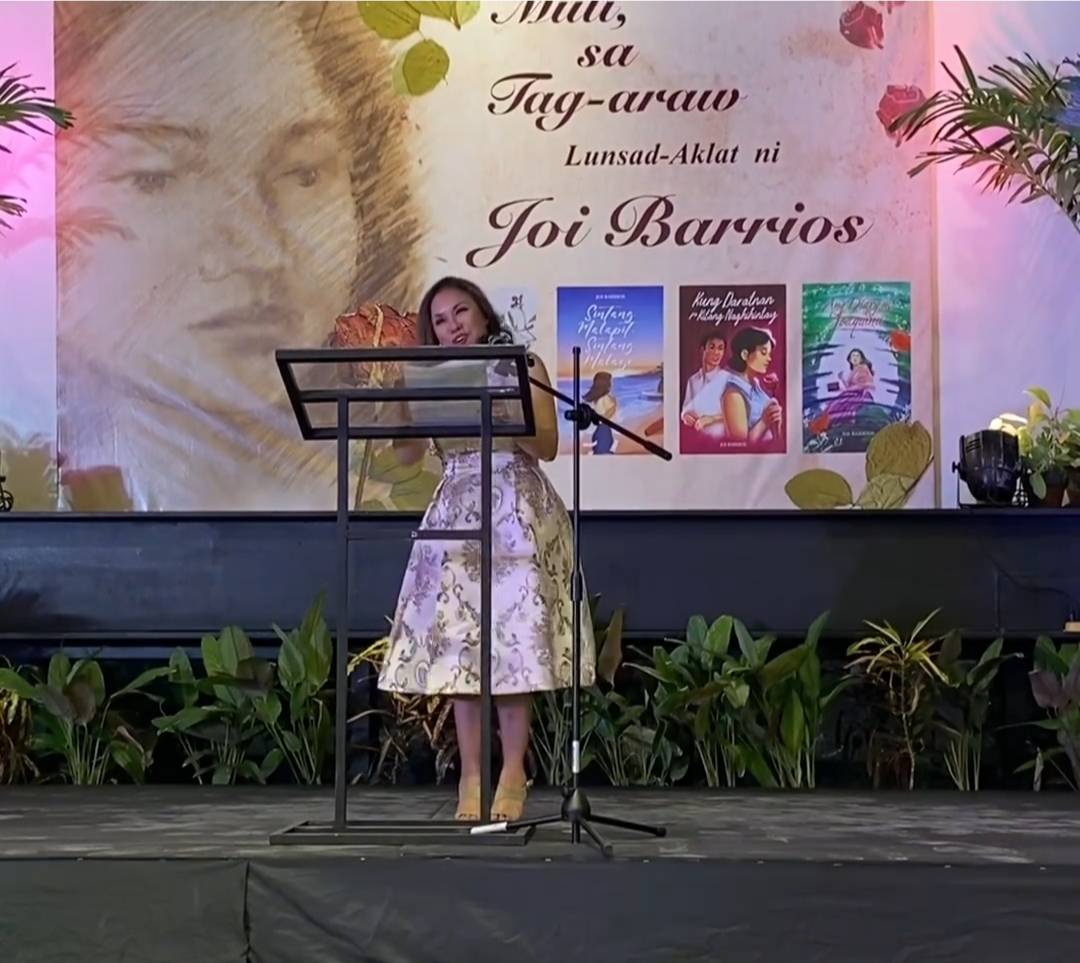

Fast-forward to June 2024, Philippine publisher Gantala Press has revived Filipino romance novels with “Librong Laso,” a series of feminist romances written in the national language. The collection features the academic Joi Barrios’ early works—“Ang Diary ni Joaquina,” “Kung Daratnan pa Kitang Naghihintay” and “Sintang Malapit, Sintang Malayo.”

Barrios’ characters Joaquina, Lisa and Fely challenge the stereotypical plots of catty rivalry among women, marriage as end goal and being Prince Charming’s choice.

Subordinate women

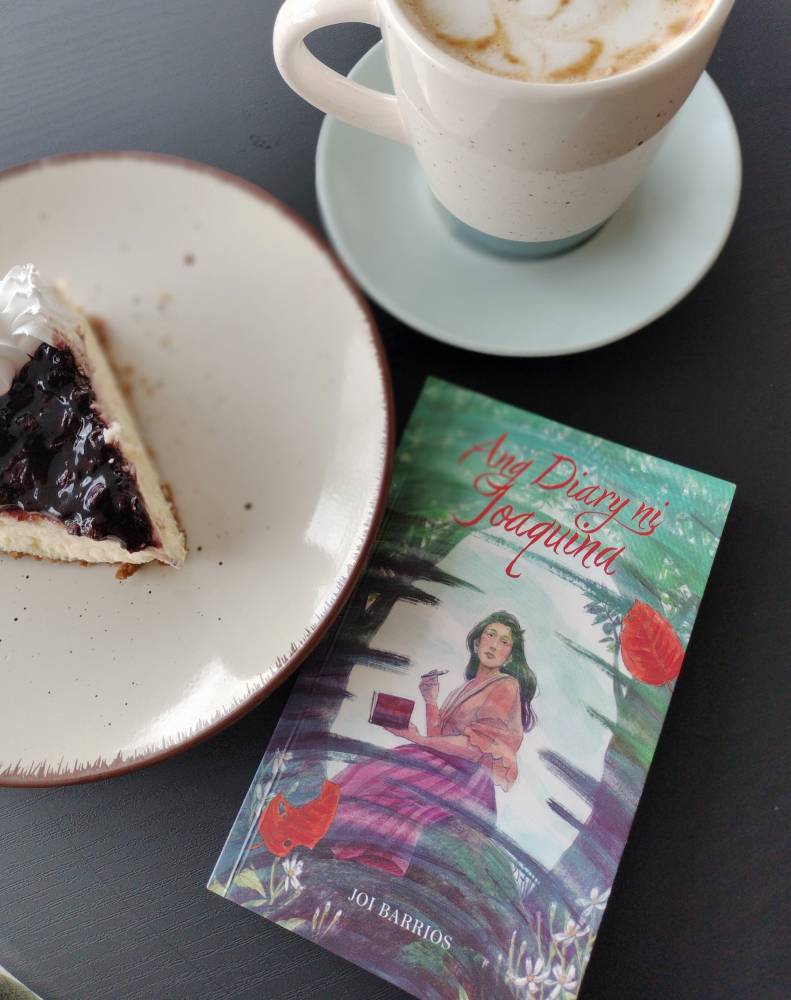

“Ang Diary ni Joaquina” revolves around Joaquina San Pedro and her diary found by her granddaughter and namesake. It’s the most engaging of the three novels because of, one, the mystery surrounding grandma Joaquina’s “craziness,” and two, the allusions to historical events.

Joaquina was locked up in the house and her writings burned by her husband Pedrito, but she was not a mental case, according to Dolores, her best friend. The two friends were polar opposites. Joaquina was submissive while Dolores was defiant, debating with the nuns in school, dressing in shorter skirts, sporting shorter hair and advocating women’s rights. Joaquina’s father Don Manuel saw Dolores as a bad influence on his daughter.

Barrios spotlights patriarchy’s chokehold on women, with Joaquina’s forced marriage to and imprisonment by Pedrito. In stream of consciousness monologues, Joaquina lamented how her wedding became her funeral and the priest’s blessing her last sacrament. Her imprisonment epitomizes what feminists Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar describe as women’s vulnerability in a patriarchal society.

Joaquina is the Asian Bertha Rochester, Edward Rochester’s first wife in Charlotte Brontë’s classic “Jane Eyre,” and the embodiment of subordinate women. In “Jane Eyre,” Rochester locks up Bertha for becoming a “surplus” to his needs, and her “hysterias” are his justification for her detention. In the same vein, Joaquina’s alleged infidelity with Vicente is Pedrito’s reason for abusing her.

Luisa, Joaquina’s teenage maid, is another subordinate woman. She was taken from her family by Joaquina’s father-in-law as payment for the debt owed to him. While she is in service, Pedrito’s older brother takes advantage of her.

The granddaughter Joaquina is also a casualty of patriarchy. Pregnant and unmarried, she is charged with immoral conduct and dismissed from the girls’ high school where she taught English.

Social unrest

In “Ang Diary…,” Barrios raises points on class, including the notion that love relationships should only occur within similar social classes. The grandmother Joaquina belonged to the landed class, while her alleged young lover Vicente sprang from farmers and servants (his mother was Joaquina’s nanny).

Significantly, ideologies clash between the social classes. Vicente’s uncle joins the peasant organization Kalipunang Pambansa ng Mga Magbubukid sa Pilipinas (KPMP), which Don Manuel loathes and fears would kill him. He pins the caretaker Kardo’s death on the KPMP and Vicente’s father, pushing Vicente and his family to leave the hacienda—and ultimately separating Vicente and Joaquina. Vicente becomes involved in the peasant movement and is tortured and shot in the head by Pedrito’s secret police.

Historically, in the 1930s, KPMP was one of the leading farmer groups in the country. Another group was Aguman ding Maldang Talapagobra, a Pampanga mass-based group of the Socialist Party of the Philippines established by Pedro Abad Santos, an older sibling of the former chief justice Jose Abad Santos.

Per Desiree Ann Cua Benipayo, author of “Honor: The Legacy of Jose Abad Santos,” agrarian unrest gained ground in Pampanga and Central Luzon in the 1930s because of the abject poverty that gripped those who tilled the land. The unrest led to protests and strikes that immobilized the haciendas. The conflict started earlier, in the late 1800s, when the Philippines became the lead supplier of cash crops to the world market. The Luzon landowners and farmers came to an agreement that the latter would clear tracts of acacia and molave trees in exchange for tenancy at a fixed rental amount. But the farmers eventually became heavily indebted to the landowners, who were said to employ usurious lending practices.

Modern slave

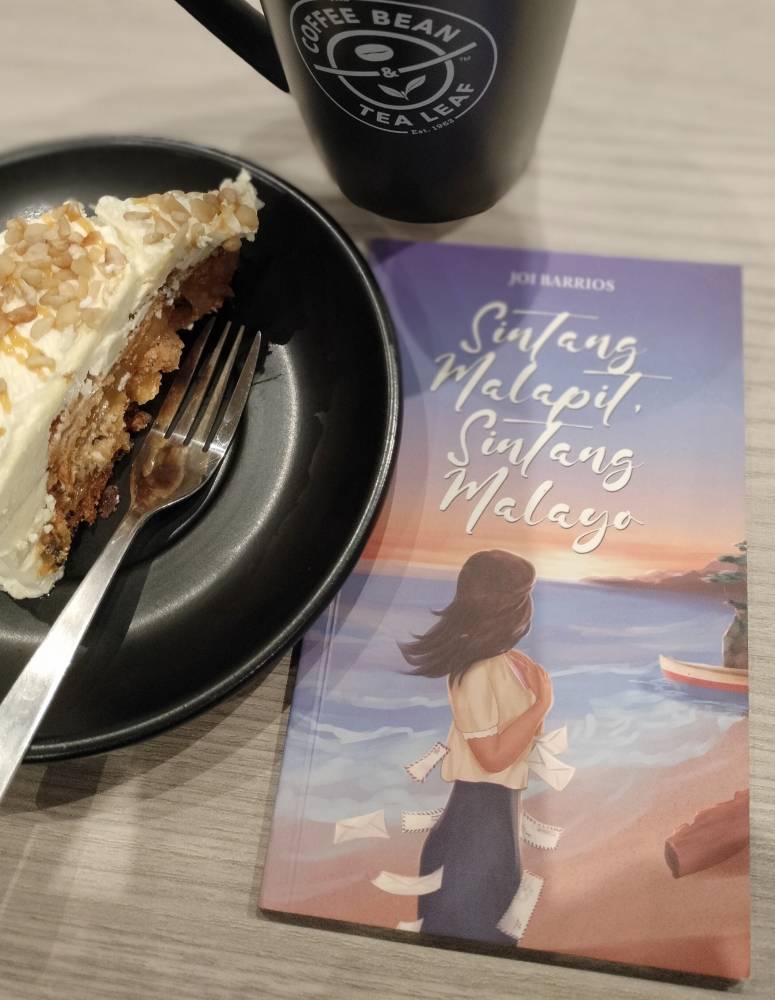

In “Sintang Malapit, Sintang Malayo,” Fely and Aaron’s romance is set against the mail-order bride scheme. The women in the town are excited for Fely and her pen pal Rainier Schmidt because she will finally get married, and to a German engineer-entrepreneur to boot! Only Aaron, Fely’s childhood friend and longtime secret love, is enraged at Fely becoming a mail-order bride.

The townsfolk find the scheme a pragmatic arrangement for Fely. She is herself thrilled at having a man pursuing her, and thinks that marrying Rainier would finally stop the townsfolk from labeling her a matandang dalaga (spinster). She hates the label, stigmatizing as it does women still unmarried at a certain age (the term “bachelor” is used to refer to aging single men).

But Rainier is a red flag. He discusses marriage as if it were a business transaction and, with a tone of finality, insinuates that Fely would have to give up teaching to be his wife and “cut the grass, make babies, and clean the house.”

Being a mail-order bride is still an attractive proposition in the Philippines, luring women with the dreamy promise of escaping from grinding poverty. They do not see beyond that promised escape, and often end up working as domestics with little or no pay in a foreign land. (Last March, it was reported that the Philippine Bureau of Immigration intercepted four bride-victims in their 20s “married” to Chinese citizens who had paid agents between P40,000 and P45,000 to expedite their documents.)

Breaking through

In Barrios’ novels, the young Joaquina and Fely break the proverbial glass ceiling restraining women. Joaquina jumpstarts her stalled writing career with a poem for her grandmother and ends her five-year estrangement from her mother. (The grandma Joaquina ended her life after learning of Vicente’s death.)

Fely turns down Rainier’s proposal, and she and Aaron become upfront with their feelings for each other.

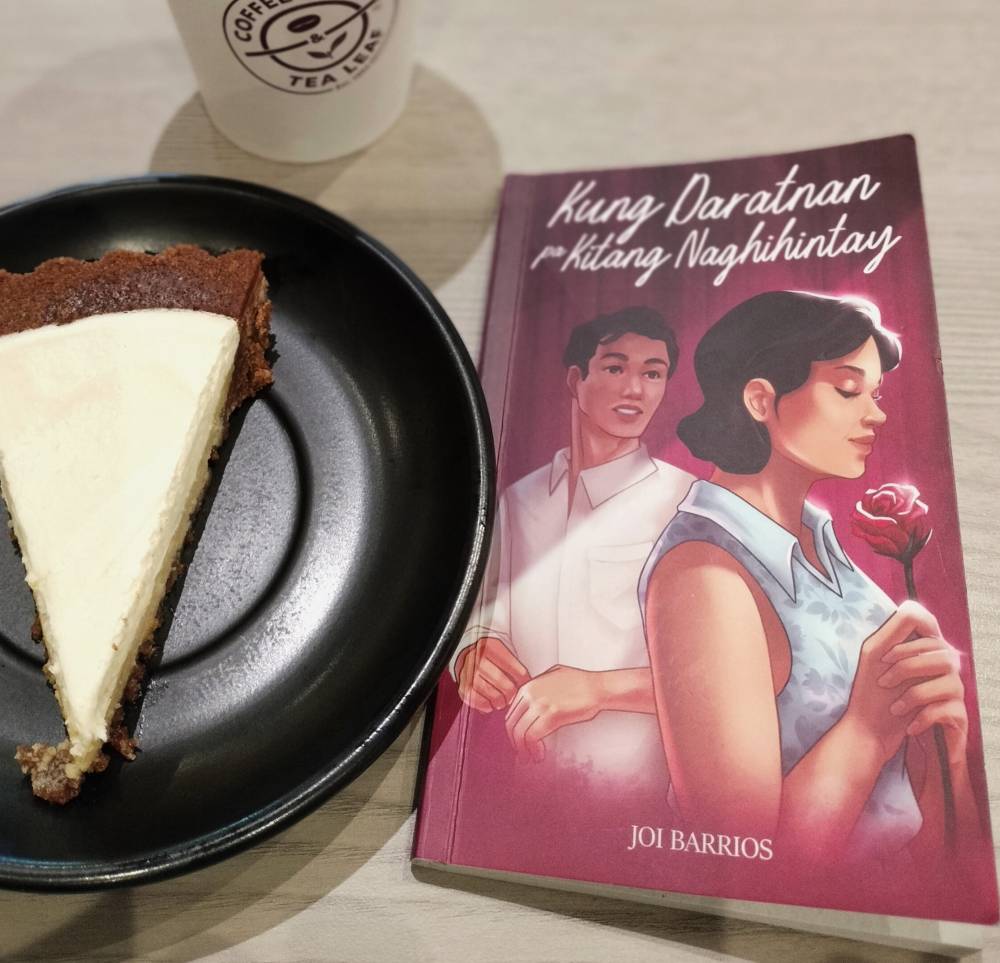

In “Kung Daratnan pa Kitang Naghihintay,” the theater actress Lisa goes on to become a playwright-scriptwriter. For her alma mater’s production, she writes about the displacement of the indigenous Aeta in favor of multinational companies. But the university president wants her work, including scenes of violence against women, revised and toned down, and the scene of the Aetas’ war dance omitted. Lisa refuses, arguing she was given carte blanche for the production.

Lisa is assertive at work, but muddled in thinking when it comes to Tony, her first love. She reconciles with him, but ghosts him when he proposes.

Her hilarious side peps up the novel. She is engaging in her soliloquies, as when she expects a crush to confess love to her, except that he tells her that he likes John. Or when her crush consoles her after she pretended onstage to be part of the bulol—carved human figurines—props when she missed her exit cue. Or when she begs a stylist to perm her hair after having it straightened earlier because her crush likes curly-haired women.

Love and sisterhood

Women in love have often been depicted as irrational, and the expectations of them are baffling. They are supposed to love sincerely and mustn’t lose their head, yet in the same breath they are to give their heart and soul. They are to anticipate their lovers’ needs, but are reproached for saying or going after what they want in a relationship. They are censured if they confess their feelings first. They are called an old maid when they choose to remain unmarried.

In her novels, Barrios redefines women in love as able to say whatever they feel without eliciting condemnation. The grandmother Joaquina didn’t have that chance, unlike her granddaughter, who found another chance at love with Roland. Lisa rejects Tony’s proposal, not because she has fallen out of love, but, as Barrios puts across, because a reconciliation is not a de facto marriage.

Significantly, love means women helping other women. Joaquina’s misery was eased by Dolores. Dina stays by Joaquina through her miscarriage and suicide attempt. Fely and Clarisse, the woman she was jealous of, become friends, and Clarisse encourages Fely to open up to Aaron about her feelings. Lisa consoles her heartbroken stage manager.

Love is beautiful, but it can get ugly when women make other women suffer because of it. In Barrios’ novels, there’s no reason women in love should be vicious.