The world runs on conflict

Human beings, being social animals, thrive on conflict. There is no perfect world of everlasting peace and harmonious co-existence in real life. If ever you find yourself in one, wake up. You’re most likely dreaming.

Conflict happens everywhere and every time two or more gather. It doesn’t have to be violent, nor profound. An “I don’t think I agree with what you said” statement already signifies conflict. Even a simple and subtle eye roll means conflict is brewing.

If even two people can already make sparks fly, imagine millions, or even billions, of people locking horns. Well, that’s the world we live in right now. Thanks to the internet, every food for thought is a feast for the massive throng. A seemingly simple, straightforward post on social media can potentially blow up and be talking points on multiple platforms.

It isn’t any different in the automotive world. The automobile is many times more complex in its global history than it is with its thousands of inner workings. A car isn’t just a car. It’s a representation of a way of life, a political belief, a religious statement, and even a declaration of superiority (Adolf Hitler’s opening of the Berlin Motor Show in 1933 comes to mind).

Think of what will happen, then, if you upend the very essence of what makes a car a car for the past 140 years or so. When you take away the very heart and soul of a car—its internal combustion engine—and replace it with a huge battery and an electric motor that doesn’t shudder and roar, you don’t just generate a conflict, you get a war. It has happened before, when electric vehicles (EVs) enjoyed some form of popularity at the turn of the 20th century, only to be edged out by ICE-powered vehicles.

To be clear, “car wars” aren’t new. It’s an essential part of the business. But since the rise of EVs, the nature of the war has shifted from corporate and marketing to technology and ideology. Before, it was all about which ICE engine performed better over the other. Today, it’s a fight for the existence of one over the other. People aren’t just asking which ICE is better. More and more people are asking if they should get an ICE-powered car or an EV.

Meanwhile, the Israel-Iran conflict may not have disrupted oil supplies as was feared, with Iran declining to block the Strait of Hormuz (which handles about 20 percent of shipments of the world’s oil and liquefied natural gas), but the volatility of oil prices and supplies remain a reality whenever large-scale conflicts like this arise, and when they do, the EV as a more stable alternative always gets into the conversation.

The Times of Israel wrote on June 27 that the Israel-Iran war was a wake-up call for Asia’s reliance on Middle East oil and gas. Asia’s dependence on Middle East oil and gas — and its relatively slow shift to clean energy — make it vulnerable to disruptions in shipments through the Strait of Hormuz, a strategic weakness highlighted by the war between Israel and Iran, wrote journalist Aniruddha Ghosal.

In another continent, Swinburne University urban mobility expert Hussein Dia was quoted by Australia news site news.com.au journalist Blair Jackson on June 26 as saying that a strangled oil supply would leave Australia “in the lurch.” He said, “If the flow of oil stopped, we would have about 50 days’ worth in storage before we ran out. The best available option to reduce dependence on oil imports is to electrify transport.”

Dia adds, “Cutting oil dependency through electrification isn’t just good for the climate. It’s also a hedge against future price shocks and supply disruptions.”

That is a point often raised by EV advocates. Still, the vast majority of the cars on the road today are powered by ICEs, as what one might expect since the technology has been in mainstream use for over a century, despite electric propulsion being invented as early as 1830s.

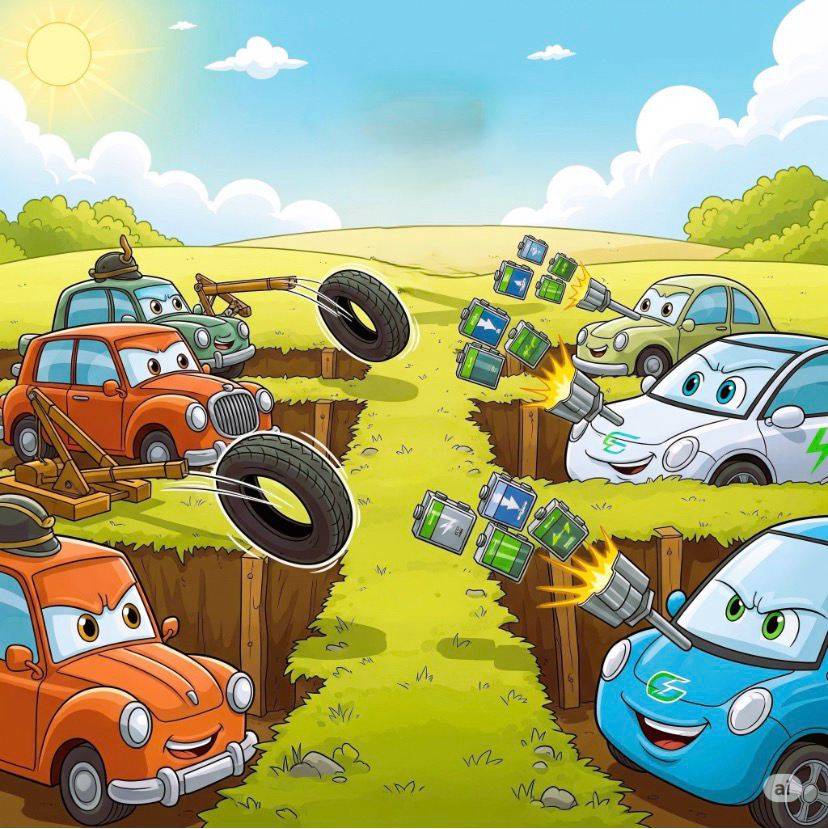

Autodrive described the ICE vs EV conflict as “the automotive version of trench warfare—entrenched, messy, and unlikely to end any time soon.”

And if I may add, this conflict is not static. The battle lines are constantly being redrawn by technological innovation, changing market sentiment, and the parallel evolution of power sources.

Booming shots were fired when the chairman of the world’s ICE superpower Toyota Motor Corp (TMC) Akio Toyoda said that 9 million battery electric cars have the same pollution impact as 27 million hybrids in an April interview with Automotive News. In the interview, he also added that an EV pollutes as much as three hybrids. These statements promptly went viral.

Toyoda said: “We have sold some 27 million hybrids. Those hybrids had the same impact as 9 million BEVs (battery EVs) on the road. But if we were to have made 9 million BEVs in Japan, it would have actually increased the carbon emissions, not reduced them. That is because Japan relies on the thermal power plants for electricity.”

TMC’s “weapon of choice” has always been its multipathway approach, rarely resorting to BEVs when dabbling in new-energy vehicles (NEVs).

TMC’s chief scientist Gil Pratt, in my interview with him in Paris in July 2024, cited a resource limitation for manufacturing BEVs. He summarized it as “1:6:90”: “If we take a certain amount of lithium to make one long-range BEV, we can use that same amount of lithium to make 6 plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs). And because we have 6 of them, even though each one doesn’t save as much carbon dioxide as the one BEV, it turns out that we can save five times as much CO2 as the one BEV. And if we’re going to look further, we can make 90 hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) because the batteries in those are much, much smaller for the same total amount of lithium, and there, again, they don’t save as much carbon dioxide as the PHEVs or the BEVs do but we can save up to 45 times as much with the same amount of lithium versus that one BEV,” he said.

Pratt added that if lithium is in short supply, then instead of only making BEVs, it makes sense to make a mixture of all three different types, with BEVs used in parts of the world where there are a lot of renewable power, and in the other parts where the renewable power is not so good, the other types of vehicles could be used.

Pratt also said that with lithium being the main mineral component of EV batteries, its global price as a commodity will still be dictated upon by the law of supply and demand. And just like any commodity, its prices are constantly fluctuating. He added that, looking at the long-term, there will be an incredible discrepancy between the need and the supply that’s expected even in the most optimistic case for new mines being set up.

That sounds logical, doesn’t it? But then again, conflict. Not all scientists subscribe to Pratt’s thinking.

“Although electric cars’ batteries make them more carbon-intensive to manufacture than gas cars, they more than make up for it by driving much cleaner under nearly any conditions,” wrote Andrew Moseman of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Climate Portal Writing Team on Oct. 13, 2022 at the climate portal of MIT.

Moseman cautioned, though, that although many full electric vehicles carry “zero emissions” badges, this claim is not quite true.

“Battery-electric cars may not emit greenhouse gases from their tailpipes, but some emissions are created in the process of building and charging the vehicles,” he said.

Sergey Paltsev, Deputy Director of the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, said that EVs are clearly lower-emissions options than ICE-powered cars. Over the course of their running lifetimes, EVs will create fewer carbon emissions than gasoline-burning cars under nearly any conditions.

InsideEVs cited a research paper published in the scientific journal IOP Science that says gas and hybrid vehicles create 6 to 9 metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions in their manufacturing, depending on the vehicle segment. EVs, on the other hand, generate 11 to 14 metric tons of CO2 emissions before going into the hands of customers.

InsideEVs’ Suvrat Kothari added: “But that’s only part of the story. Once EVs hit the road, they begin paying off that carbon debt and their overall ‘emissions’ start decreasing. Hybrids and gas vehicles, on the other hand, head in the opposite direction, growing their carbon emissions over time. After a certain number of miles, an EV can potentially clear that debt entirely.”

Experts and some European data point out that an EV pays off its ‘carbon debt’ of manufacturing emissions after about 18,000 km of travel or within two years. And as electricity grids transition to more renewable sources, EVs by then will also become greener with their source of power. Thus, the most environmentally friendly and cost-effective way to power an EV is to use solar panels, according to the Energy and Climate online site of the Queensland Government.

But then again, conflict. How is your solar panel produced, where does it come from and how will it be disposed at the end of its useful life? The eye-roll moments never end.