40 years of ‘steady but shallow growth’

When Economic Planning Secretary Arsenio Balisacan and economist Hal Hill published their book “The Philippine Economy: Development, Policies, and Challenges” in 2003, they put into words what many had long observed: the Philippines’ growth story was “one of the world’s major development puzzles.”

After World War II, the Philippines boasted one of the highest per capita incomes in East Asia. Even as late as 1980, most analysts still considered it part of the second generation of Asian “tiger” economies.

Yet, as Balisacan and Hill observed, the nation’s development outcomes “have been disappointing by any yardstick.” They said the Philippines missed nearly the entire Asian boom that surged from the late 1970s through the mid-1990s.

A key turning point came in the mid-1980s, when labor-intensive industries began migrating to China and lower-wage economies in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean). The Philippines, dogged by political uncertainty and structural problems, struggled to compete.

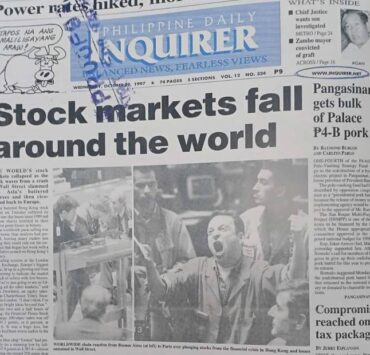

It was in this moment of economic distress, in 1985, that the Philippine Daily Inquirer was born, telling the story of a nation searching for its place in a rapidly transforming region. Across four decades, the Inquirer’s archives chronicled the Philippines’ attempts at restructuring, the political upheavals, and the major steps toward development.

“Over the last 40 years, the Philippine economy has experienced steady but shallow growth, characterized more by consumption-driven expansion than by sustained productivity gains,” Leonardo Lanzona, an economist at the Ateneo de Manila University, said in an interview. “The country avoided periods of collapse seen elsewhere in the region, but it also did not undergo the deep structural transformation that propelled its neighbors into higher-income status.”

Crises of the 1980s

The Inquirer began telling such stories at a moment Balisacan and Hill would later describe as “stagnation, then deep crisis.” Between 1984 and 1986, a dangerous combination of political turmoil and economic mismanagement triggered one of the steepest contractions in the country’s post-independence history, a meltdown unmatched until the Covid-19 pandemic sent the local economy plunging 9.4 percent in 2020.

This reason is that the Philippines entered the 1980s burdened by a mountain of foreign debt. In the preceding decade, the government loosened its purse strings and went on a borrowing binge to cushion the impact of the global oil shocks of 1974 and 1979. When interest rates spiked, the cost of paying those external loans became expensive, pushing the government to default.

The ensuing debt moratorium and the country’s reliance on an International Monetary Fund loan ushered in years of belt-tightening, marked by strict fiscal and monetary controls that set off one of the worst recessions in the nation’s history. The economy contracted by 7 percent in 1984 and by another 6.9 percent the following year. That unraveling was intensified by the 1983 assassination of opposition leader Benigno Aquino Jr., which rattled investors and deepened public mistrust in the Marcos dictatorship.

Erratic recovery

Following the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution and the restoration of democracy, the economy began to recover as political stability returned. Foreign capital flowed back, which helped strengthen the peso, while regional trade winds again turned favorable. Growth between 1987 and 1991 averaged 4 percent.

But as Balisacan and Hill pointed out, the rebound was “erratic.” A “mild crisis” struck between 1992 and 1993 despite major reforms during the later part of the Aquino administration and under the Ramos presidency, with annual growth settling at measly 0.4 percent and 2.2 percent during those two years.

A series of coup attempts in the early 1990s, severe power shortages, natural disasters—including the 1991 eruption of Mt. Pinatubo—and the closure of US military bases that once contributed as much as 5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) all weighed heavily on the recovery.

Yet from 1994 to 1997, the country experienced what Balisacan and Hill described as an “important period in Philippine economic history” characterized by a wave of reforms, from opening the economy to foreign investors to revamping the tax system and strengthening the central bank.

But that momentum was interrupted by the Asian Financial Crisis from 1998 to 2001, though the Philippines escaped with far less damage than its neighbors.

Structural problems persist

After two decades of stagnation, the World Bank said the Philippine economy began to stir again in the mid-2000s, with the Philippines avoiding a recession when the global financial crisis hit in 2008.

“We moved from the debt crisis and instability of the 1980s to a more stable, service-led economy with lower inflation, stronger external buffers, and a vibrant OFW-IT-BPM-remittance engine,” John Paolo Rivera, a senior research fellow at the state-run Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), said in an interview.

But even before the Wall Street-centered financial meltdown unfolded, doubts lingered about whether the Philippines could sustain its newfound momentum. The World Bank had warned that growth was riding on an exceptionally favorable global environment—one that could quickly turn. Economists also highlighted a familiar list of structural constraints: chronic underinvestment in infrastructure, low overall investment, stubbornly high unemployment, and the continuing exodus of highly skilled workers.

As the Philippines clawed its way out of the deep recession caused by the pandemic, the economy ran headlong into a new set of headwinds, ones now casting a long shadow over the Marcos administration’s growth ambitions.

Uncertain outlook

Abroad, escalating trade tensions have introduced a fresh kind of uncertainty. Geopolitical flash points, from US-China rivalry to regional security risks, have further clouded the outlook. At home, a widening corruption scandal has dealt a sharp blow to business and consumer confidence.

The consequences are already showing. Major multilateral institutions expect the country to miss its growth target again in 2025, the third straight year it will fall short, after underperforming in both 2023 and 2024. For Ateneo’s Lanzona, “any disruption in global trade, technology, or geopolitics can weaken exports, while the domestic sector lacks the capacities needed to absorb displaced workers or expand into higher-value markets.”

PIDS’s Rivera sees a different but overlapping hazard. He warned that climate risks and governance weaknesses, compounded by global financial volatility, could form a disruptive combination.

“More frequent and stronger typhoons, floods, and droughts can repeatedly hit agriculture, infrastructure, and vulnerable communities, while any loss of confidence in institutions due to corruption or policy slippage can magnify the economic damage through slower investment, higher risk premium and currency pressure,” he said.