A DENR challenge: When politics creeps into protected areas

When the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) investigated the controversial Captain’s Peak Garden & Resort built on one of the famed Chocolate Hills of Bohol province, the agency discovered that about 14,000 hectares out of the 19,000-ha protected area were classified as alienable and disposable land (ADL).

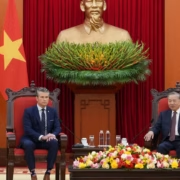

“You can actually own a hill,” Environment Secretary Ma. Antonia Yulo-Loyzaga said during a roundtable discussion at the Inquirer office last week.

The resort owner “actually had a title,” Yulo-Loyzaga recalled. “What he did wrong was that he started his project without going through the ECC (environmental compliance certificate) process ordered by the Protected Area Management Board (PAMB).”

ADLs refer to “lands of the public domain which have been the subject of the present system of classification and declared as not needed for forest, mineral purposes or national parks,” according to the Revised Public Land Act of the Philippines.

But while landowners may have titles over such lands, what they can construct in those areas still depends on the PAMB’s approval.

Calls to amend law

And here lies the challenge: because most PAMB members are locally elected officials, such as barangay chairpersons, most of them would prefer to prioritize land development to appeal to constituents.

Simply put, political considerations tend to trump environmental concerns.

There are two main area classifications in a protected area, Yulo-Loyzaga explained: The strict protection zone, where nothing can be built or altered; and the multiple-use zone, where certain developments can be allowed, like a small resort or a renewable energy project.

“If the PAMB decides to go one way—if they want to say, ‘Oh, the multiple-use zone is now here’—so the strict protection zone can be shrunken,” she added. “So that’s the challenge. You have people, because of need or motivation, who would want certain developments to happen.”

In the Chocolate Hills case, the issue got more complicated when certain areas were enrolled in the Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System (E-Nipas) without being checked if they were ADLs. “They did not check whether there were any politically made settlements or if it was already in use, or if it was being claimed, if prior rights were there,” she said.

These examples are the reason why the DENR chief has made a proposal to amend the 2018 E-Nipas law, one of her major thrusts since being appointed by President Marcos in July 2022.

For starters, the composition of the PAMB should be reviewed.

“If all the barangay captains are there, typically the political influence will also be there. What happens now is you can have a PAMB of 50 to 100 people, most of whom are barangay captains, all of whom will be wanting some sort of development because of their political needs, not necessarily conforming with the protected area’s needs.”

The DENR legal department has proposed several amendments to the law in a memorandum dated Sept. 11 and submitted to the House committee on appropriations.

Memo to House

One of them seeks to include police power and eminent domain in the powers of the DENR secretary when it comes to the management of Nipas lands, and another wants the law to “expressly recognize the secretary’s power to cancel or modify PAMB resolutions.”

Another sought to “limit the membership of the barangays” in the PAMB composition and adopt an “appropriate method of clustering the barangays to determine their representation in the PAMB.”

This clustering should be “determined by the BMB (Biodiversity Management Bureau) with due regard to the existing ecosystem of the protected area concerned,” the memo added.

The E-Nipas Act is “a great law,” Yulo-Loyzaga said. “But when [it] bumps into reality, you have to really think of how you can amend this law.” INQ