A love affair with Cory, a covenant with democracy

“Tomorrow, tomorrow, we will run stories about the murder of Ninoy.”

That was Eugenia Duran-Apostol, the publisher and editor in chief of the colorful, weekly family magazine Mr. & Ms., talking at the top of her voice the moment she arrived at the office at CityTrust Building on Edsa one morning in August 1983.

She came the night before from the house of former Sen. Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. on Times Street, Quezon City, where she felt the weight of the murder: “They killed Ninoy, they killed Ninoy.”

Ninoy was assassinated upon his return to the Philippines at the Manila airport on Aug. 21, 1983, a Sunday.

With mixed feelings, the Mr. & Ms. staff gathered around EDA, as she was fondly called, at her small round table, waiting for her full report.

‘Special Edition’ is born

Apostol had brought along an album of pictures of the slain senator covering the many facets of his life—from boyhood to schooling, marriage, and political life—as well as photos of his wife, Corazon “Cory” Aquino.

EDA sequestered the pictures from Ninoy’s grieving sisters—among them Mila Aquino-Albert—all of whom were her schoolmates at the Holy Ghost College in Mendiola. It was her scoop, and the magazine went to town with those rare pictures.

About two million people showed up for Aquino’s funeral 10 days later, the longest ever seen in Philippine history. But the major dailies ignored it. The headline of the biggest paper the following day read: “Two killed by lightning.”

Apostol was fuming: “Tomorrow, tomorrow we will run stories about the murder of Ninoy.”

In the next few days, she was printing another weekly, the black-and-white version of Mr. & Ms., and it was called Mr. & Ms. Special Edition for Justice and National Reconciliation.

It had 16 pages of photographs showing Aquino’s body, the millions of people who came to view the wake, and the massive funeral parade that wound through the streets of Manila for almost 12 hours. The tabloid sold some half a million copies. “Thanks to Ninoy,” a staff member said in jest, commenting on the sale.

Madam who?

Week after week, the special edition would use the Aquino photos.

One late afternoon weeks later, Apostol announced to the staff that “Madam” would visit the Mr. & Ms. offices.

Until then, Philippine society knew only one Madam—first lady Imelda Marcos. So the staff received it with mixed feelings, anxious that Imelda would come to give them a dressing-down for all the anti-Marcos stories. Anything was possible under the Marcos administration.

Surprise! It was Cory Aquino in person, indeed looking like a plain housewife, unlike the Imeldific, bringing along more Aquino family photos, including the young Kris Aquino campaigning for her dad in the 1978 elections.

Madam Cory easily blended in with the starstruck staff. And before anybody knew it, it marked the beginning of a love affair with Cory, though no one had any idea that the widow would one day become president of the republic.

Cory found solace that here was a magazine generously accommodating and highly appreciative of the many stories about Ninoy, unlike the establishment press which even demonized him, probably on orders of the Marcos administration. And she never imposed on the staff what to do.

After 100 issues, the special edition was turned into a book.

‘Inquiry of the Century’

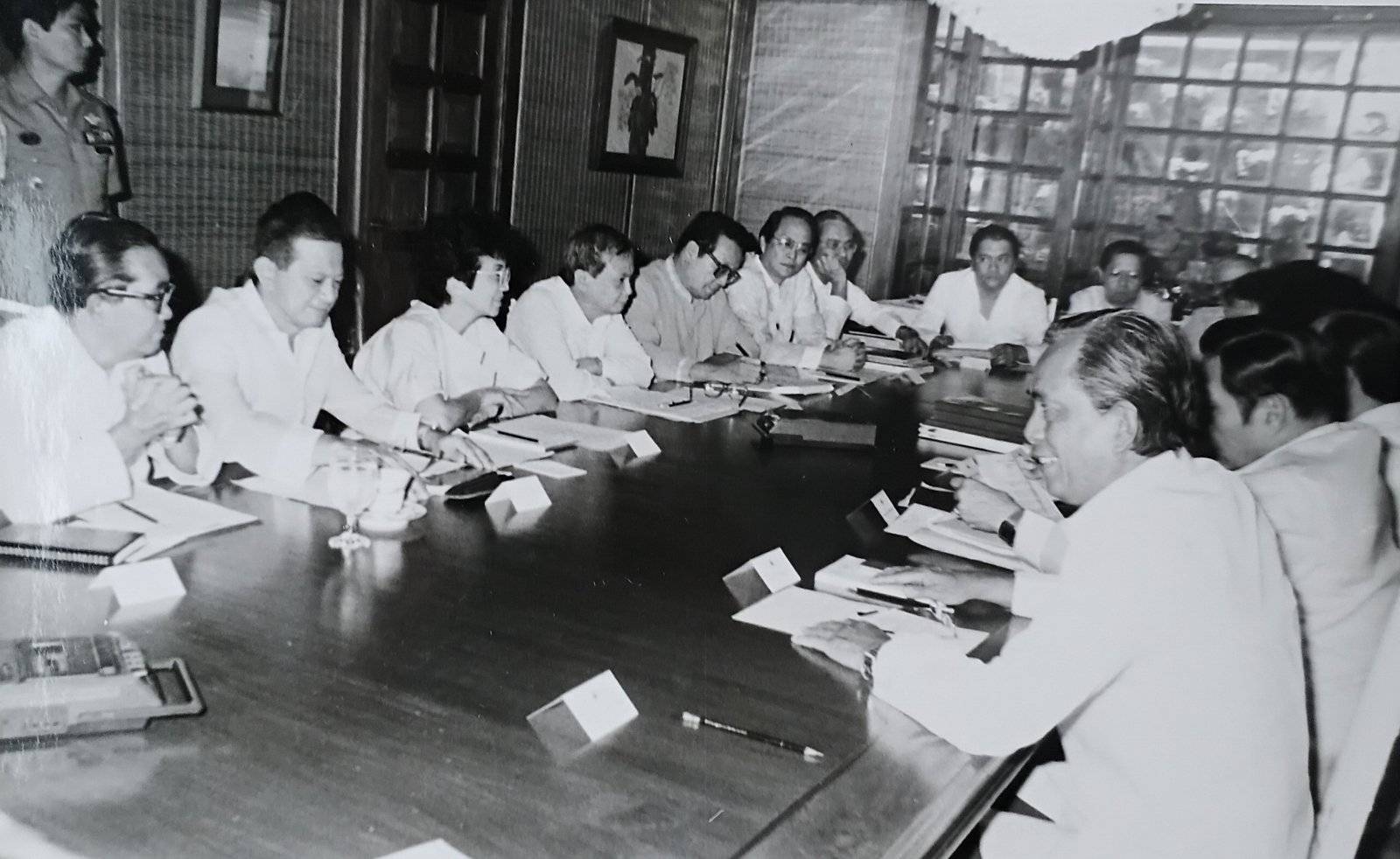

In October 1983, President Marcos Sr. created the five-person Agrava commission to look into the military’s involvement in the Aquino assassination.

Three days before the start of the investigation, Apostol launched the “Weekly Inquirer” to chronicle the “Inquiry of the Century.”

In November 1985, because of rising public and US pressure, Marcos announced he would hold a snap presidential election in February the following year to seek a fresh mandate from the Filipino people.

Cory Aquino took the dare and ran for president. Marcos ran with his former Foreign Secretary Arturo Tolentino, while Cory’s running mate was former Sen. Doy Laurel.

In response, Apostol led a team of journalists, young and old, in launching the Philippine Daily Inquirer (PDI), its maiden issue hitting the streets on Dec. 9, 1985. Most of us at Mr. & Ms. moved to the daily.

PDI provided the Cory-Doy tandem the platform it needed. It sent some of its best reporters to cover their campaign, beginning with Belinda Olivares-Cunanan and JP Fenix.

As Cory’s presidential campaign gained momentum, the Inquirer reached the provinces, its circulation ballooning so rapidly that it had to seek printing in other companies, some owned by Marcos cronies.

Marcos and Tolentino won according to the Commission on Elections, but the military-backed People Power Revolt in February 1986, the first of its kind in the world, honored Cory as the new president and Doy the new vice president.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

Cory in Malacañang

Covering Saint Cory wasn’t that easy.

The world loved her so much that it wasn’t easy to get close to her. In 1986, Time Magazine named her Person of The Year. One needed to fight for space with journalists from around the world.

We would see Time Magazine’s Sandra Burton, who traveled with Ninoy Aquino to the Philippines on the same flight and day he was murdered, come in and out of the Palace with ease. Some foreigners would show up in summer clothes while local newsmen were required to wear formal suits. No jeans, no rubber shoes.

In the face of such discrimination and the difficulty of covering the president, among other issues, the young Palace reporters (well, 40 years ago we were young), tried to boycott the Palace, only to be given a dressing-down by then Inquirer columnists Letty Jimenez-Magsanoc and Ninez Cacho-Olivarez, among others.

“This administration is not run by newspapers,” Cory’s first executive secretary Joker Arroyo lectured the reporters one morning. His point being: The government would do what it had to do. The media did not dictate the administration’s agenda.

The Inquirer gave President Aquino the respect she deserved. Senior editors were sent to cover her during her foreign travels.

When she first flew to the United States to speak at the joint session of the US Congress, no less than then editor in chief Louie Beltran was deployed to cover it. “I will go to the States now, hangga’t mabango pa ako,” Cory told reporters.

Overall, the coverage was fine, glowing. Saint Cory could still walk on water, so to speak.

Looking back, under the despotic Marcos regime, Mr. & Ms. and its baby the Inquirer were the Opposition’s papers, providing them a platform.

In one interview, Apostol declared that the Inquirer “had unqualifiedly supported Cory throughout her campaign, her call for civil disobedience, and her assumption to the presidency.” We were a young witness to that unqualified support.

But when Aquino became president, judging from the editors’ policy pronouncements during staff meetings, the Inquirer pivoted and adopted the universal code for journalists—a “policy of objectivity and editorial independence vis-à-vis her government.” There were no sacred cows, we were told. That was a tectonic shift.

The paper began running stories and opinion pieces critical of the Aquino administration. And these stories displeased Cory and some of her Cabinet members, with presidential spokesperson Rene Saguisag calling us the “Philippine Daily Error.”

We were all admittedly young, most of the reportorial staff anyway, and far from perfect. Every story was done in a hurry. We were all journalists in a hurry. And until Magsanoc took over as editor in chief, the paper looked like what she described as an “unmade” bed.

Months into the Aquino administration, blackouts hit the entire country, with up to 12-hour supply interruptions.

By late 1986, cracks in the Cory administration were showing, her officials split between two factions—Joker and his Apostles and the Council of Trent led by Jose Concepcion—and fighting over turf. Complaints about government projects and services began leaking left and right, including about Cory’s relatives, with tips coming from Marcos loyalists and the “Sorristas,” or disillusioned Cory followers.

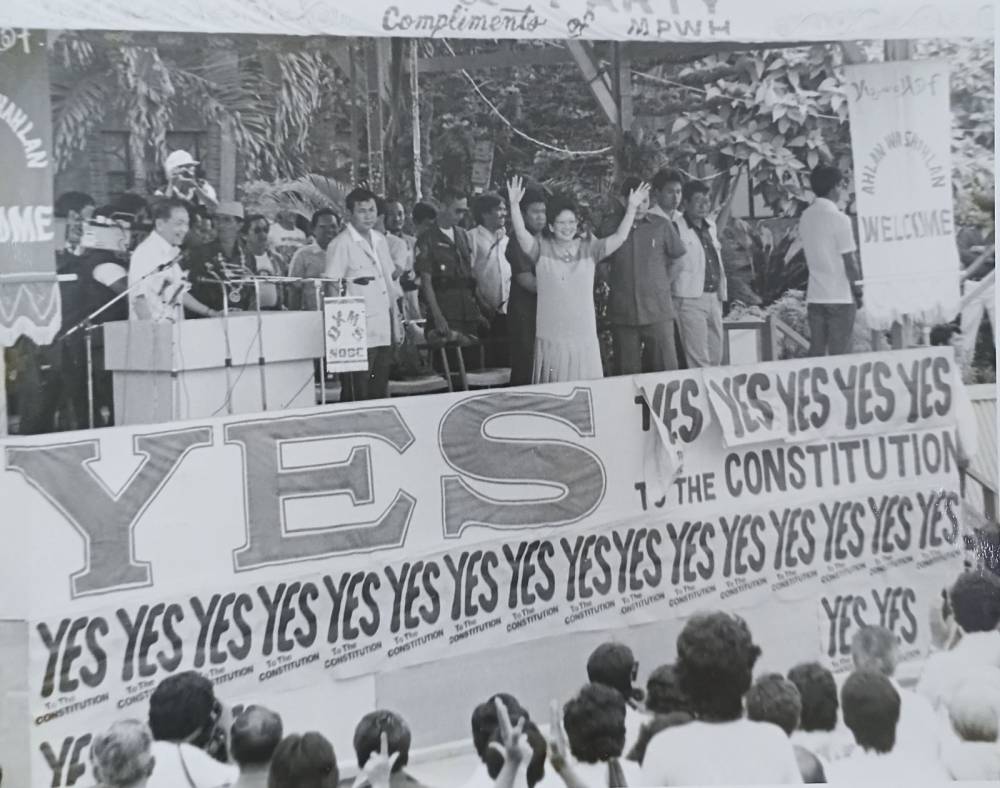

The Cory Constitution was resoundingly ratified nationwide through a plebiscite in February 1987, several months after Marcos loyalists took over the Manila Hotel. The siege failed to gain popular support.

But critics raised points against the 1987 Constitution, which some people found valid much later. It failed, for instance, to define a dynasty, or put a limit to the number of politicians’ relatives entering the government. The 1987 elections also saw the rise and revival of the political careers of so many Aquinos and Cojuangcos.

The Aquino government fell short of clearly planning its land reform program, supposedly the centerpiece of Cory’s administration. Her own family’s Hacienda Luisita fought the program beyond her term.

Cory and the Palace probably expected too much from the Inquirer, with some citing the paper’s rise to prominence that began in that small Mr. & Ms. office after the Aquino assassination, unmindful that the men and women behind the paper were all journalists fighting the Marcos dictatorship long before the tarmac tragedy.

Covering the Aquino presidency soon became a I-love-you-I-hate-you affair.

In its news reportage and opinion pieces, the Inquirer stood by Cory Aquino and the preservation of democracy, and was firmly against the coup d’etats staged several times by soldiers loyal either to Marcos or then Defense Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile, who tried to unseat her.

The Inquirer had its own battle with Enrile as it held him accountable for his Marcos past. We reported that Enrile admitted he faked his premartial law ambush and cheated Cory of some 300,000 votes in the 1986 snap elections. Enrile denied all this in his memoir published in September 2012, 40 years after the declaration of martial law. Early on, we resisted his historical revisionism.

Still, we were not Cory’s favorite paper, we were told. (Though she was not hostile to us or to me particularly.)

Through all this, Cory Aquino was a simple president. We were all witness to this fact while covering her at the Palace. By 8 o’clock every morning, she would walk from her Arlegui house to the Palace compound in simple clothes, hardly wearing jewelry. Sometimes she would wear the same dress some other days.

“I am a simple and conservative woman,” she said in an interview. “I repeated my clothes even in public functions. When I went on a state visit to the US, I wore simple suits because I was representing a third world country. Maybe I like a good pair of shoes, but I will survive without them.”

But Cory was far from perfect, either. She had feet made of clay. She got happy, mad, or unforgiving, depending on the situation.

When Enrile, the man allegedly behind the many attempts to destabilize her administration, was brought up in a discussion, Cory was always straightforward: “I will pray for him.” She said so sometimes with sarcasm.

Sometimes she was aloof, sometimes she was sweet to those covering her in the Palace. She would occasionally invite Malacañang reporters and serve them merienda with food she herself had prepared.

When she was not in the mood to talk to us, no issue could force her to do so. No ambush interviews. That gave birth to the weekly “Magtanong sa Pangulo” radio program.

Or if you wanted an answer, be in Malacañang before 8 a.m. and catch her before she reported for work. We would give her some written questions and wait for her answers in the afternoon. She never failed to provide answers even if it was too close to deadline time.

Against the wishes of some friends, Cory sued Beltran, who was by then a columnist for the Philippine Star, for libel. Beltran had written that the President hid under her bed at the height of the bloody August 1987 putsch.

She made a spectacle of herself because of that case, saying “Your Honor” in addressing Ramon Makasiar, the Manila judge hearing her case. Almost simultaneously, Makasiar would sue his clerk of court, this reporter, and the Inquirer for another case, this time involving a family member.

Makasiar eventually dropped his case against us. Cory didn’t drop hers. Makasiar found Beltran guilty, but the Court of Appeals overturned Makasiar’s decision in November 1995.

Still, Cory was an Inquirer favorite. Under Magsanoc’s watch, Cory was named Inquirer’s Filipino of the Year, first in 1997, with Jaime Cardinal Sin; and again in 1999, both for restoring and preserving Philippine democracy.

In 2006, Cory, Apostol, and Magsanoc were named among Time Magazine’s Asian Heroes, for their role in helping restore Philippine democracy in the wake of the Marcos dictatorship. The tribute began with an article calling Aquino a “saint of democracy.”

Indeed, Cory’s campaign and Palace media bureau chief, now People Asia editor Joanne Ramirez, asked some Palace reporters the question in January 2024: How well do we remember Cory?

We wrote: “We should remember Cory Aquino for leading the restoration of democracy, for living a very simple life; for not wanting to extend her term and for the peaceful transition of power; and for instilling decency in government.”

At her wake at the Manila Cathedral in August 2009, the Aquino family invited Inquirer columnist Conrado de Quiroz, who had been critical of the Cory administration in his columns, to deliver a eulogy.

De Quiros was the most surprised.

In his piece titled “One Good Person,” de Quiroz wrote: “I wasn’t an ardent fan of Cory at the beginning. I was an ardent critic. I came from the ranks of the red rather than the yellow, and looked at the world from the prism of that color. It got so that in one program Kris Aquino invited me to (I don’t know if she remembers this), she took me to task for it. It was an Independence Day show, and during one break, Kris turned to me and said: “Why are you so mean to my mom?”

“It’s not easy finding a clever answer to an accusation like that with breathtaking candor.

“Maybe it’s not so strange that people who start out being enemies on grounds of principle end up being friends on those same grounds.

“But bad people are there; we know that only too well. Just as well, good people are there too; we know that even more so.

We know the latter because we had someone walk with us who was so. Someone who was so disinterested in power she accepted it gravely as a matter of duty and gave it up gracefully as a matter of trust, for which she remains an awesome force even in death. Someone who, while she lived, showered not very small kindnesses on others in their hour of need or bereavement, having known bereavement herself and the comfort of empathy as much as the empathy of comfort, for which she continues to live with us even in death. Someone who proved once before as Joan of Arc and who will prove once again like El Cid the terrifying and wondrously prophetic vision of her faith: The exalted shall be humbled and the humble exalted.”

Cory did what she had to do. And the Inquirer did what it had to do. What transpired between the leader and the journalists was nothing personal.

In the words of the great Letty Jimenez-Magsanoc: It was purely journalism.