Agusan’s Mt. Magdiwata: From logging hot spot to living forest

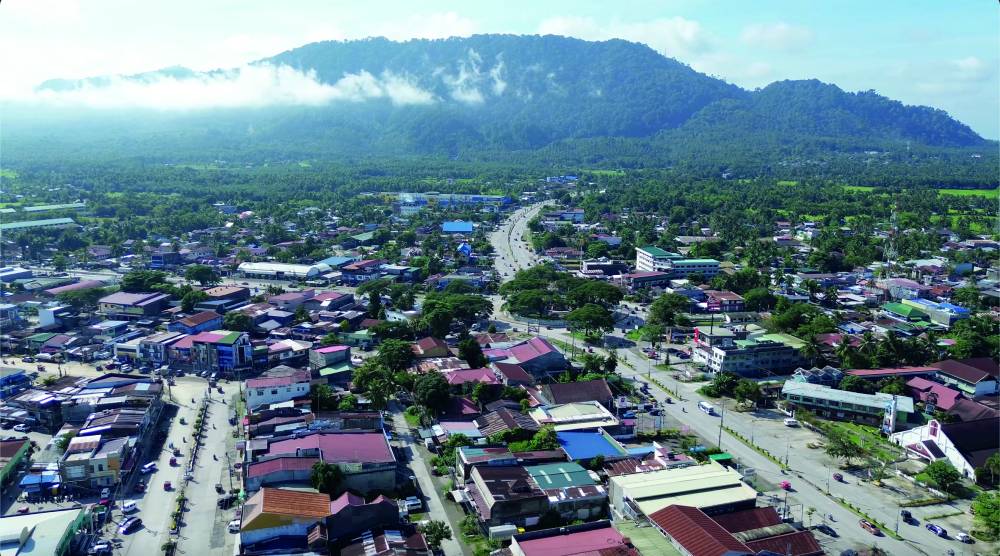

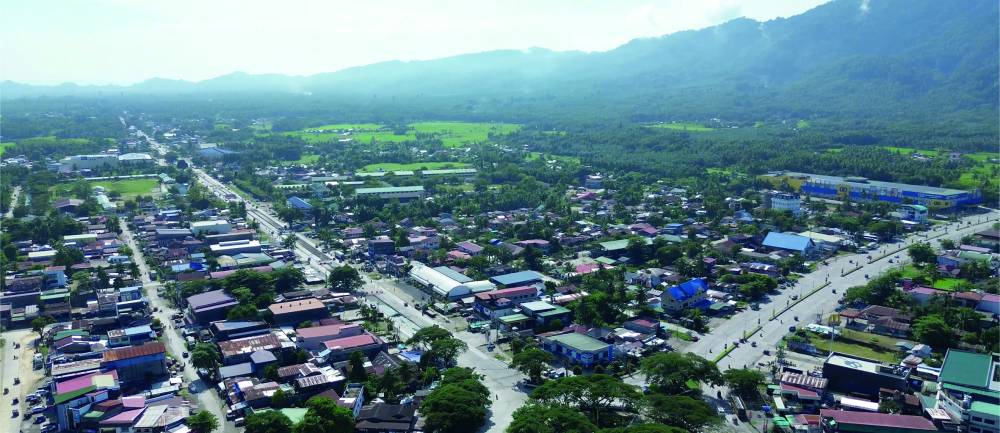

SAN FRANCISCO, AGUSAN DEL SUR—Rising 633 meters (2,077 feet), Mt. Magdiwata towers over this bustling town of about 80,000 people that serves as the center of trade and commerce of Agusan del Sur province.

San Francisco’s old-timers and those who had frequented it long enough could immediately compare the mountain’s condition through the years. Today, it is almost lush green, far from the barren landscape that it was more than 20 years ago.

Over two decades of protection and restoration work, mainly spearheaded by the San Francisco Water District (SFWD), had made the difference in Magdiwata’s ecological health.

A recent flora and fauna study done by experts from the Caraga State University (CSU) has established its rich biodiversity, raising its importance for environmental conservation and preservation.

Reforestation effort began in 1997, after then President Fidel V. Ramos issued Presidential Proclamation No. 282 in 1993 that set aside some 1,000 hectares for a community forest management project and 1,658 ha as Mt. Magdiwata watershed forest reserve, out of a vast reservation assigned to state-owned National Development Co. in 1980.

At that time, forest cover was only 695 ha, a result of decades of large-scale logging operations from the 1960s through the 1970s, and then timber poaching on the remaining trees in the 1980s to supply lumber-milling plants that proliferated around town.

The water district took up the cudgels for Magdiwata’s protection as the water distributed to households through its pipelines comes from the mountain’s springs.

SFWD general manager Elmer Luzon recalled how they convinced farmers tilling in the upland area to transfer their farms to the buffer zone, located downhill, to give way to reforestation activities.

These farmers were given technical and financial support to pursue agroforestry through organic farming methods. Their community was then organized to become the “social fence” that will prevent activities destructive to the mountain and its nascent forest cover.

More than a decade into the effort, Luzon said they discovered the doubling of water production capacity of SFWD’s major spring sources. In 2017, they calculated that four spring sources SFWD had tapped into could supply the needs of up to 12,000 households, including the growing number of commercial establishments then.

This bolstered SFWD’s resolve to protect Magdiwata.

Last year, SFWD commissioned the flora and fauna study to support the formulation of its watershed management plan.

“The plan aims to strike a balance between addressing socioeconomic concerns and protecting the environment, while respecting the diverse social and cultural beliefs of San Francisco, Agusan del Sur,” Luzon said.

The 220-page report, “Biodiversity Update on Flora and Fauna and the Socioeconomic Study of the Mt. Magdiwata Watershed and Forest Reserve (MMWFR) and Indicative Watershed Management Plan,” came out in December last year, after nearly five months of fieldwork and analysis.

Home to ‘Ibong Adarna’

The ecological richness of Magdiwata, which has now 97 percent forest cover, came to light in the study done by biodiversity expert Romell A. Seronay, director of CSU’s Center for Research in Environmental Management and Eco-Governance, and Nilo Calomot, an environmental science expert at CSU.

The vibrant Philippine trogon (Harpactes ardens), one of the most colorful endemic birds in the country, which is associated with the mythical “Ibong Adarna,” is among the many captivating discoveries of Seronay and Calomot in Magdiwata.

The bird appeared on July 7 last year, when the research team was deep in their fieldwork.

Calomot, who also serves as a consultant for SFWD, described the presence of the Ibong Adarna species as a symbol of Magdiwata’s rich biodiversity. He cited the watershed’s ecological role not just as a crucial water source for local communities but more importantly as a biodiversity haven.

The study described the watershed as a tropical lowland evergreen forest teeming with life, providing shelter to towering trees, rare plant species and diverse wildlife.

The study found that the forest supports 167 plant species, including rare varieties like Ficus fiskei and Artocarpus blancoi, plants that play vital roles in soil stabilization and maintaining water quality.

The lush forest floor teems with species such as the poison dart plant (Aglaonema commutatum) and zebra plant (Alocasia zebrina), which thrive in the moisture-rich environment, supporting a range of amphibians and reptiles. Among them are the rare Nyctixalus spinosus, a tree frog, and the venomous North Philippine temple pit viper (Tropidolaemus subannulatus).

Vital stopover

The report also noted an abundance of birdlife on Mt. Magdiwata, identifying 47 bird species within the watershed, of which 29 were endemic to the Philippines.

Among the most abundant are the Philippine bulbul (Hypsipetes philippinus), whose calls echo through the forest. The diversity of avian life reflects the health of the ecosystem, which also serves as a vital stopover for migrating birds, according to the report.

Aside from birds, the watershed is also home to 132 species of volant mammals, including fruit bats like Cynopterus brachyotis, which play key roles in pollination and seed dispersal, further supporting the forest’s biodiversity.

The report also documented a diverse array of plant life, totaling 167 species across 61 families and 112 genera in its initial survey.

The survey highlights the predominant presence of towering tree species, particularly from the Dipterocarpaceae family, including notable species such as bagtikan (Parashorea malaanonan), red lauan (Shorea negrosensis), white lauan (Shorea contorta), almon (Shorea almon), mayapis (Shorea palosapis) and tanguile (Shorea polysperma).

In addition, researchers also found trees from the Burseraceae family, like Canarium species, that also play a prominent role in shaping the landscape.

They noted that the dominance of these tall, canopy-forming trees significantly influences the forest structure, limiting the growth of understory species. The understory is primarily made up of plants from the Araceae family, such as the poison dart plant, snakeplant (Dracaena trifasciata), badjang or swamp taro (Crytospermum merkusii), Schismatoglottis calyptrata and uway or rattan (Calamus spp.).

Ongoing threats

Most of the plant species identified, so far, are trees that contribute to the high canopy cover throughout the watershed. These are followed by a variety of shrubs, which tend to grow as wildlings around the mother trees of species like tanguile, mayapis, and pili-pili.

The survey also noted the presence of herbs and ferns, adding further layers of complexity to the watershed’s flora that help sustain its ecosystem that, in turn, help regulate water supply for agricultural and domestic use.

The watershed is home to 15 species listed as conservation priorities by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, including the critically endangered Amboyna wood or Pterocarpus indicus and the vulnerable Aquilaria cumingiana. These species are at significant risk due to habitat loss and illegal exploitation, underscoring the need for ongoing conservation efforts.

The Mt. Magdiwata Watershed is deeply integrated into the lives of local residents. Barangays such as Alegria, Karaus and Bayugan 2 rely on its resources for agricultural activities, particularly palm oil cultivation.

As the population grows and the demand for land increases, tensions between conservation and development have emerged, especially that the town has seen rapid growth since 2016 that it now hosts three big shopping malls.

The recent socioeconomic study revealed that while many residents are adapting to the watershed’s protected status, balancing economic needs with environmental preservation remains a challenge.

More than three years ago, there were attempts to develop a 4-ha sloping land inside the watershed’s 1-kilometer buffer zone into a housing project. This was met by protests from residents and SFWD officials.

The SFWD also vehemently opposed the inclusion of the watershed in the ancestral domain area to be granted the Manobo tribe, fearing its protection measures will falter.

What they are after, Luzon said, is for locals to not go thirsty.