AI chatbot helps Malawi farmers survive storms

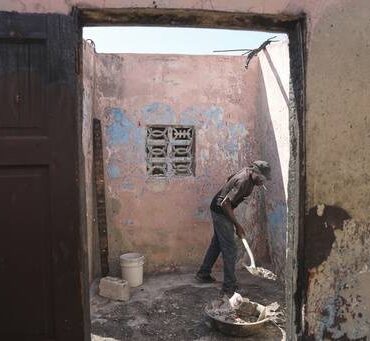

MULANJE, MALAWI—Alex Maere survived the destruction of Cyclone Freddy when it tore through southern Malawi in 2023. His farm didn’t.

The 59-year-old saw decades of work disappear with the precious soil that the floods stripped from his small-scale farm in the foothills of Mt. Mulanje.

He was used to producing a healthy 850 kilograms of corn each season to support his three daughters and two sons. Maere salvaged just 8 kg from the wreckage of Freddy.

“This is not a joke,” he said, remembering how his farm in the village of Sazola became a wasteland of sand and rocks.

Freddy jolted Maere into action. He decided he needed to change his age-old tactics if he was to survive.

Maere is now one of thousands of small-scale farmers in the southern African country using a generative artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot designed by the nonprofit Opportunity International for farming advice.

The Malawi government is backing the project, having seen the agriculture-dependent nation hit recently by a series of cyclones and an El Niño-induced drought. Malawi’s food crisis, which is largely down to the struggles of small-scale farmers, is a central issue for its national elections next week.

More than 80 percent of Malawi’s population of 21 million rely on agriculture for their livelihoods and the country has one of the highest poverty rates in the world, according to the World Bank.

The AI chatbot suggested Maere grow potatoes last year alongside his staple corn and cassava to adjust to his changed soil. He followed the instructions to the letter, he said, and cultivated half a soccer field’s worth of potatoes and made more than $800 in sales, turning around his and his children’s fortunes.

‘Without worries’

“I managed to pay for their school fees without worries,” Maere beamed.

AI has the potential to uplift agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa, where an estimated 33 million to 50 million smallholder farms like Maere’s produce up to 70 percent to 80 percent of the food supply, according to the UN International Fund for Agricultural Development.

Yet productivity in Africa—with the world’s fast-growing population to feed—is lagging behind despite vast tracts of arable land.

As AI use surges across the globe, it is helping African farmers access new information to identify crop diseases, forecast drought, design fertilizers to boost yields, and even locate an affordable tractor. Private investment in agriculture-related tech in sub-Saharan Africa went from $10 million in 2014 to $600 million in 2022, according to the World Bank.

But not without challenges.

Africa has hundreds of languages for AI tools to learn. Even then, few farmers have smartphones and many can’t read. Electricity and internet service are patchy at best in rural areas, and often nonexistent.

“One of the biggest challenges to sustainable AI use in African agriculture is accessibility,” said Daniel Mvalo, a Malawian technology specialist. “Many tools fail to account for language diversity, low literacy and poor digital infrastructure.”

‘Advisor’

The AI tool in Malawi tries to do that. The app is called Ulangizi, which means advisor in the country’s Chichewa language. It is WhatsApp-based and works in Chichewa and English. You can type or speak your question, and it replies with an audio or text response, said Richard Chongo, Opportunity International’s country director for Malawi.

“If you can’t read or write, you can take a picture of your crop disease and ask, ‘What is this?’ And the app will respond,” he said.

But to work in Malawi, AI still needs a human touch. For Maere’s area, that is the job of 33-year-old Patrick Napanja, a farmer support agent who brings a smartphone with the app for those who have no devices. Chongo calls him the “human in the loop.”

“I used to struggle to provide answers to some farming challenges, now I use the app,” Napanja said.

Farmer support agents like Napanja generally have around 150 to 200 farmers to help and try to visit them in village groups once a week. But sometimes, most of an hourlong meeting is taken up waiting for responses to load because of the area’s poor connectivity, he said. Other times, they have to trudge up nearby hills to get a signal.