All the Presidents’ mien

BAGUIO CITY—Everyone can now have a glimpse of the stories about the country’s 17 presidents, who have shaped Philippine society since 1899, at the century-old Mansion House, one of the top attractions in Baguio City.

First lady Liza Araneta-Marcos has repurposed the 14.7-hectare presidential summer residence as a museum. She formally opened the Mansion’s massive American colonial era iron gates to the public on Sept. 8 and launched free five-day tours of rooms that showcase the achievements of all presidents, no matter what challenges and controversies occurred during their administrations.

The ceremonial opening took place three days before the birthday of her late father-in-law, Ferdinand Marcos Sr., and 13 days from the date when an older generation of Filipinos witnessed him declare martial law on Sept. 21, 1972.

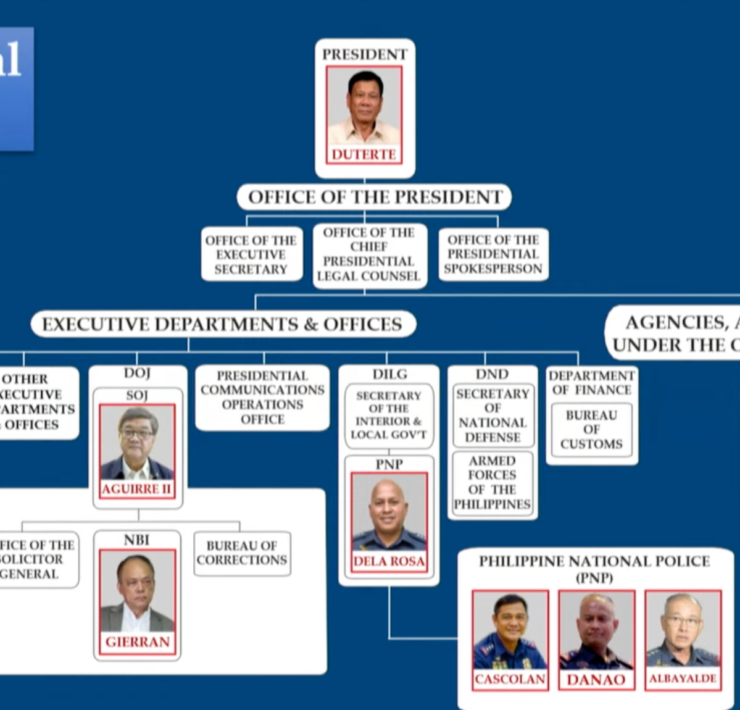

Marcos Sr.’s booth offers a very detailed account of his career as a lawyer, as a soldier fighting during World War II and as a political giant when his presidency began on Dec. 30, 1966, and his administration’s last years in the 1980s. It also features world events to establish Marcos’ impact on the global stage.

His nemesis, the late President Corazon Aquino (who served from Feb. 25, 1986 to June 30, 1992), was described as the political opposition’s rallying point following the Aug. 21, 1983, assassination of her husband, former Sen. Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr.

Mrs. Aquino led a “mass demonstration against Marcos, which is commonly referred to as the Edsa 1 People Power Revolution,” according to her Mansion profile.

Her presidency is credited with pushing for a new Constitution that “delimited presidential authority” in 1987. Mrs. Aquino’s entry says she also pursued peace talks that resulted in the formation in 1989 of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (now known as the Bangasamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao).

All in the family

The Mansion exhibits called attention to the country’s legacy presidencies from Marcos Sr. and his son, incumbent President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. (elected June 30, 2022), to Mrs. Aquino and her son, the late President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III (June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016).

There are also rooms dedicated to the late President Diosdado Macapagal (Dec. 30, 1961-Dec. 30, 1965), and daughter, President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, who used to frequent Baguio during her nine-year tenure (Jan. 20, 2001 to June 30, 2010). Baguio residents had the most interaction with Arroyo, whose childhood was spent at the Mansion.

The Mansion honored Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo, the first president to lead a newly formed Philippine Republic following the 1896 uprising against Spanish colonial rule, and who fought the Americans before it set up its colonial government at the start of the 20th century.

It has not been clear whether Aguinaldo ever set foot inside the Mansion, which was home to American governors general, said the hero’s great grandson Emilio Aguinaldo Suntay.

The Palace had wanted to borrow some of Aguinaldo’s keepsakes for his Mansion booth, Suntay said.

Suntay and his sister, Nenita Tanedo, are the grandchildren of the hero’s youngest daughter, Cristina, and they have been storing Aguinaldo’s memoirs, his wheelchair, huge wooden desk and other belongings, including the fraying relic of what is arguably the first Philippine flag, at a family museum on Happy Glen Loop in Baguio City.

Treat

Some of Baguio’s older residents, who suffered through martial law, have maintained their distance from the Mansion project.

“We hope this is not another form of historical revisionism. Art and culture, when misused, can gaslight the victims of despotism and plunderous rule,” said 66-year-old author, poet and activist Luchie Maranan.

But for other residents, it was a treat to finally enter the Mansion, one of many historic buildings in the city they could only watch through the palatial iron gates.

The first time it opened to the public was shortly after the Edsa Revolution, although guests at the time were only allowed access to the lush gardens beyond its massive gate.

Few have been allowed to walk through its distinctive sloping road while no one has been allowed to wander through the 11-ha compound’s forests.

The Mansion was put up in 1908 as the summer home of American colonial leaders, starting with William Cameron Forbes, who was appointed governor general in 1909—the same year Baguio was opened as a chartered city.

It has yet to undergo Baguio’s cultural mapping process.

Portions of the area are believed to overlap with Ibaloy ancestral land claims. In 2010, the pumping station serving the Mansion was included in Certificates of Ancestral Land Title covering Baguio’s Wright Park, which the Supreme Court nullified in 2019.

Forbes had difficulty securing colonial government investments for building up Baguio, which was designed and built by colonial authorities as America’s only hill station where officials can hold office to escape Manila’s summer heat, according to Robert Reed, author of “The City of Pines: The Origins of Baguio as a Colonial Hill Station and Regional Capital.”

But the success of townsite land sales—when rich Americans and Filipinos purchased Baguio property as early as 1906 to finance road constructions—eventually convinced the colonial government to pour money into the construction of public buildings, “and had authorized the construction of the Mansion House, the official highland residence of the governor general,” Reed says in the book.

Forbes hired Japanese gardeners to manicure the Mansion’s lawns and maintain its flower beds.

Century-old

The Mansion officially became the president’s summer home at the start of the commonwealth when wartime President Manuel Quezon governed in 1935. It was badly damaged at the end of the war by American bombers during the country’s liberation from Japanese occupying forces in 1945, but was immediately restored and improved.

In 2008, the Mansion turned a century-old, and its heritage marker was installed by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, after it was declared a national historical landmark in 2009.

During Christmas and Holy Week, people have been allowed to enter and take pictures and “selfies” in front of the huge lawn where garden blooms spell out “The Mansion.”

Malacañang social secretary Bianca Zobel said close to 500 people stop at the Mansion gates each day, and up to 2,000 tourists come during weekends. The Mansion, she said, is now open to them so they can learn about the country’s history and its presidents.

“The Mansion House is a tourist attraction—it always was, but it was behind closed gates,” she said. Zobel said the government would undertake more renovations and “fix the gardens so we can offer walking tours.”

Most importantly, she said, the Mansion House museum may facilitate understanding and unity.