As communists streamed into Saigon, a few reporters kept photos, stories flowing

BANGKOK—They’d watched overnight as the bombardments grew closer, and observed through binoculars as the last US Marines piled into a helicopter on the roof of the embassy to be whisked away from Saigon.

So when the reporters who had stayed behind heard the telltale squeak of the rubber sandals worn by North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops in the stairs outside The Associated Press office, they weren’t surprised, and braced themselves for possible detention or arrest.

But when the two young soldiers who entered showed no signs of malice, the journalists just kept reporting.

Offering the men a Coke and day-old cake, Peter Arnett, George Esper and Matt Franjola started asking about their march into Saigon. As the men pointed out their route on a bureau map, photographer Sarah Errington emerged from the darkroom and snapped what would become an iconic picture, published around the world.

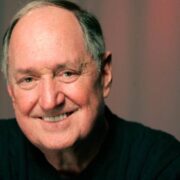

Fifty years later, Arnett recalled the message he fed into the teletype transmitter to AP headquarters in New York after the improbable scene had played out.

“In my 13 years of covering the Vietnam War, I never dreamed it would end as it did today,” he remembers writing.

The message never made it: after a day of carrying alerts and stories on the fall of Saigon and the end of a 20-year war that saw more than 58,000 Americans killed and many times that number of Vietnamese, the wire had been cut.

End of an era

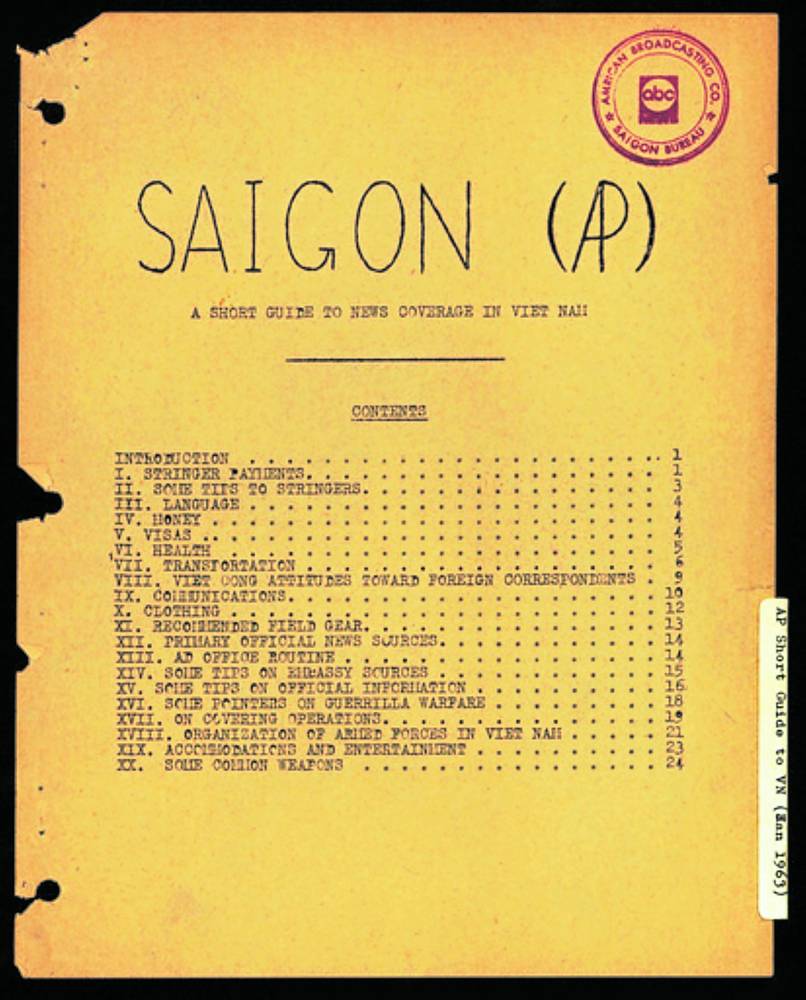

The fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975 was the end of an era for the AP in Vietnam that began when it opened its first office there in 1950. Arnett left in May, and then Franjola was expelled, followed by Esper and a bureau wouldn’t be reestablished until 1993.

The AP received five Pulitzer Prizes for its reporting of the war, including back-to-back-to-back wins by bureau chief Malcolm Browne in 1964, photo chief Horst Faas in 1965 and Arnett in 1966.

Four AP photographers were killed covering the war, and at least 16 other AP journalists were injured, some multiple times.

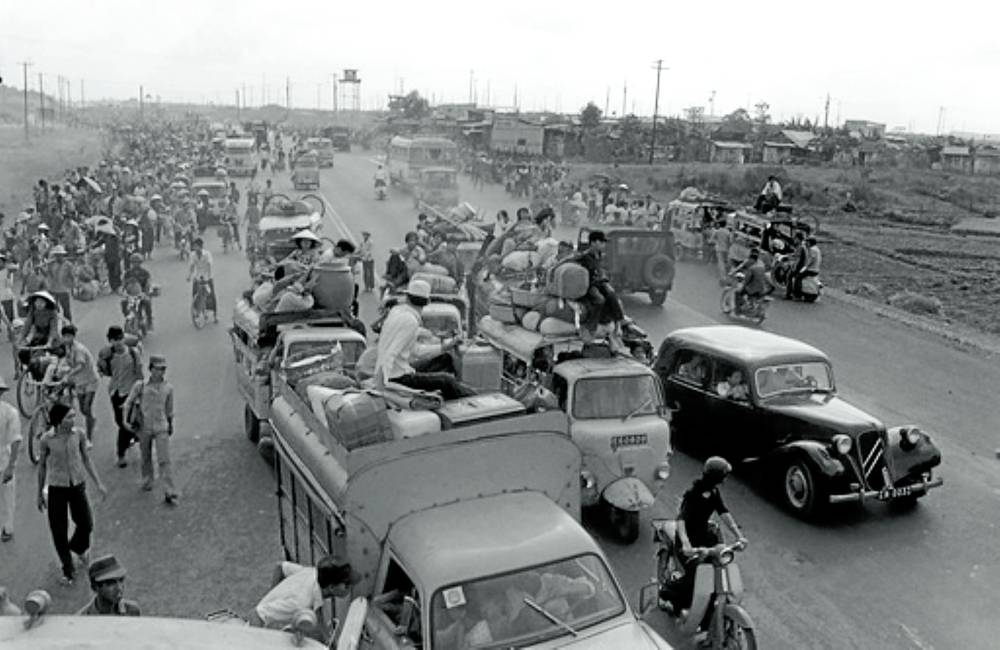

By 1975, the number of American forces in Vietnam had been drawn down to a handful, following the 1973 Paris Peace Accords in which US President Richard Nixon agreed to a withdrawal, leaving the South Vietnamese to fend for themselves.

The AP’s bureau had shrunk as well, and as the North Vietnamese Army and its allied Viet Cong guerrilla force in the south pushed toward Saigon, most staff members were evacuated.

Arnett, Esper and Franjola volunteered to stay behind, anxious to see through to the end what they had committed so many years of their lives to covering.

“I saw it from the beginning, I wanted to see the end,” Esper said.

On April 30, 1975, Arnett watched through binoculars as a small group of US Marines that had accidentally been left behind clambered aboard a Sea Knight helicopter from the roof of the embassy — the last American evacuees.

He called it in to Esper in the office, and the story was in newsrooms around the world before the helicopter had cleared the coast.

Out on the streets

At 10:24 a.m., Arnett was writing a story about the looting of the US Embassy looting when Esper heard on Saigon Radio that South Vietnam had surrendered and immediately filed an alert.

Out on the streets, Franjola, who died in 2015, was nearly sideswiped by a Jeep packed with men brandishing Russian rifles and wearing the black Viet Cong garb. Arnett then saw a convoy of Russian trucks loaded with North Vietnamese soldiers driving down the main street and scrambled back into the office.

“‘George,’ I shout, ‘Saigon has fallen. Call New York,’” Arnett said. “I check my watch. It’s 11:43 a.m.”

It was about 2:30 p.m. when the two NVA soldiers burst in, accompanied by Ky Nhan, a freelance photographer who worked for the AP, who announced himself as a longtime member of the Viet Cong.

“I have guaranteed the safety of the AP office,” Arnett recalled the photographer saying. “You have no reason to be concerned.”

As Arnett, Esper and Franjola pored over the map with the two NVA soldiers, they chatted through an interpreter about the attack on Saigon, which had been renamed Ho Chi Minh City as soon as it fell.

The young men showed the reporters photos of their families and girlfriends, telling them how much they missed them and wanted to get home.

“I was thinking in my own mind these are North Vietnamese, there are South Vietnamese, Americans — we’re all the same,” Esper said.

“People have girlfriends, they miss them, they have the same fears, the same loneliness, and in my head I’m tallying up the casualties, you know nearly 60,000 Americans dead, a million North Vietnamese fighters dead, 224,000 South Vietnamese military killed, and 2 million civilians killed. And that’s the way the war ended for me.”