Budget process observers from civil society ‘very worried’

There was a sense of guarded optimism among them, the designated “nonvoting observers,” when the 2026 national budget process began in August. For the first time, the House of Representatives invited civil society organizations (CSOs) to formally take part in the review of the government’s P6.7-trillion spending plan—a reform that lawmakers touted as heralding a “new era of transparency.”

But months later, that optimism gave way to disappointment even as the chamber passed House Bill No. 4058—its version of the budget bill vis-à-vis the Senate’s—on second reading on Friday.

The bill now contains the amendments made by the House budget amendments review subcommittee (BARSc) in relation to the P255-billion cut from the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH).

It also carries an amendment introduced by Mamamayang Liberal Rep. Leila de Lima to slash Vice President Sara Duterte’s proposed funding down to P733 million in an effort to “discipline a brat” who repeatedly refused to answer for the Office of the Vice President’s budget.

But for reform advocates like Kenneth Isaiah Abante, the promise of a more participatory and transparent budget has fallen short. Many of the red flags they raised early on—including P230 billion for “pork and patronage programs”—were left largely unaddressed in the House-approved budget.

Pork allocations

“The disillusionment now of civil society in the budget process is, while there was an attempt to bring us in a more formal process, it seems like many of the recommendations still fell on deaf ears,” said Abante, co-convenor of the People’s Budget Coalition (PBC) of church, business, and civic groups monitoring public spending.

“So we’re very concerned, we’re very worried. And people are indeed losing trust in the integrity of the budget process … [all] of this points to the fact that the system really hasn’t changed,” he told the Inquirer.

Based on their analysis, the House-approved version still contains at least P230 billion worth of pork and patronage allocations, despite repeated warnings from watchdogs and reform advocates.

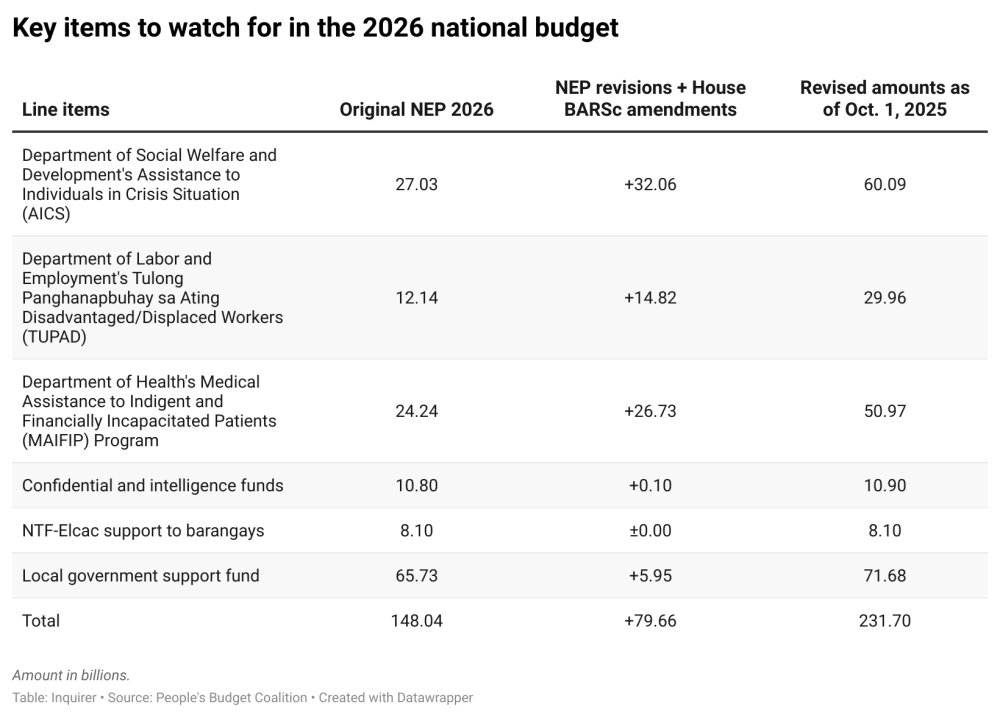

They specifically flagged the additional P32.06 billion for the Department of Social Welfare and Development’s Assistance to Individuals in Crisis Situation (AICS); additional P14.82 billion for the Department of Labor and Employment’s Tulong Panghanapbuhay sa Ating Disadvantaged/Displaced Workers (Tupad); and additional P26.73 billion for the Department of Health’s Medical Assistance to Indigent and Financially Incapacitated Patients (Maifip) programs.

They also took note of the additional budget for the Department of Agriculture’s farm-to-market roads even though they have repeatedly been suspected to be overpriced, and the retention of “still-flaggable” projects under DPWH, such as questionable multipurpose buildings.

“If you see the magnitude of what is inside the budget, all of this worsens the culture of patronage and pork, and it’s orders of magnitude bigger than the proposals of civil society,” Abante said.

‘Slush fund for corruption’

Abante’s sentiments were shared by minority lawmakers who have been lobbying for the complete removal or at least reform of the P250-billion unprogrammed appropriations (UA) in the budget but whose amendments were thumbed down by House appropriations chair, Nueva Ecija Rep. Mikaela Suansing.

“The majority’s rejection of these basic accountability measures is a clear signal that they want to keep the UA as a slush fund for corruption,” said ACT Teachers Rep. Antonio Tinio, who wanted to restore an original provision that required presidential approval for the release of UA.

“By removing presidential approval, they’re creating plausible deniability for corruption.”

At least, Abante said, budget advocates scored some small victories, such as the allocation of P1 billion for the University of the Philippines’ Project Noah on disaster risk reduction and management, and P56 billion in additional education funding, all sourced from the DPWH cuts.

But beyond the specific provisions of HB 4058, the advocates were also not satisfied with the actual budget process, as civil society representatives were often not given enough notice or time to review key amendments.

No transparency

In a joint statement, CODE NGO, GoodGovPH, Sigaw ng Kabataan, FOI Youth Initiative, and Ibon Foundation criticized the House BARSc for suddenly convening on Sept. 22 to tackle the realignment of the DPWH budget cuts without prior notice to CSOs and even minority lawmakers.

The Suansing-led BARSc livestreamed the deliberations, but the groups argued that “livestreams and token observers do not equal transparency.”

If at all, these are “a smokescreen used to claim public participation while denying citizens genuine access to documents, deliberations, and decision-makers,” they added.

For many CSOs, Abante said, the turning point came when Congress failed to act on the creation of an open budget transparency server.

Such a mechanism would have allowed citizens and analysts to track every peso from agency proposals to bicameral conference adjustments, similar to how election transparency servers now allow independent monitoring of vote tallies.

This “was one of my tests for sincerity in the process. But it did not materialize,” Abante said.

And so the advocates ended up doing a grueling review of heavyset PDF files—the National Expenditure Program, HB 4058, against the BARSc amendment report—every time they wanted to participate in the deliberations.

Suansing earlier said they would have to study such a server.

But “technically, it’s feasible,’’ Abante said. “The House already reports on these data tables. It just takes the leadership to say yes. So many are game to build this server: journalists, civic tech volunteers, civil society.”

Promise to open the bicam

As Congress prepares for the bicameral conference committee that will finalize the 2026 budget, CSOs are again demanding that the talks be opened to the public—something both chambers promised but have yet to institutionalize.

In July, then Speaker Martin Romualdez filed House Resolution No. 94 intending to open the traditionally closed-door bicameral conference to third-party observers. The resolution, however, has yet to be adopted following his resignation on Sept. 17 amid allegations linking him and other lawmakers to questionable public works projects.

These allegations were precisely what triggered the reforms in the first place.

“What I find new this year [is that] there are so many people whose eyes are on the budget,” Abante said. “And if they don’t deliver on their promises, we will protest. And remember, the people are angry. We’ve seen that in the [marches] across the country.”

“If our government leaders don’t listen, that’s even more cause for protest and the people’s anger. We just have to keep up the pressure, but also commend them when they do the right things,” he added.

Ultimately, Abante said, the responsibility for a transparent, reform-oriented budget lies with the country’s top officials.

“The President is accountable to the budget,” he added. “The best way to counteract from our institutional level is the threat of the veto. So we call on him to veto things that are porky, that worsen patronage, infrastructure projects that don’t conform with nature-based solutions in flood control.”