Charter framer pushes dynasty ban up to ‘4th degree’

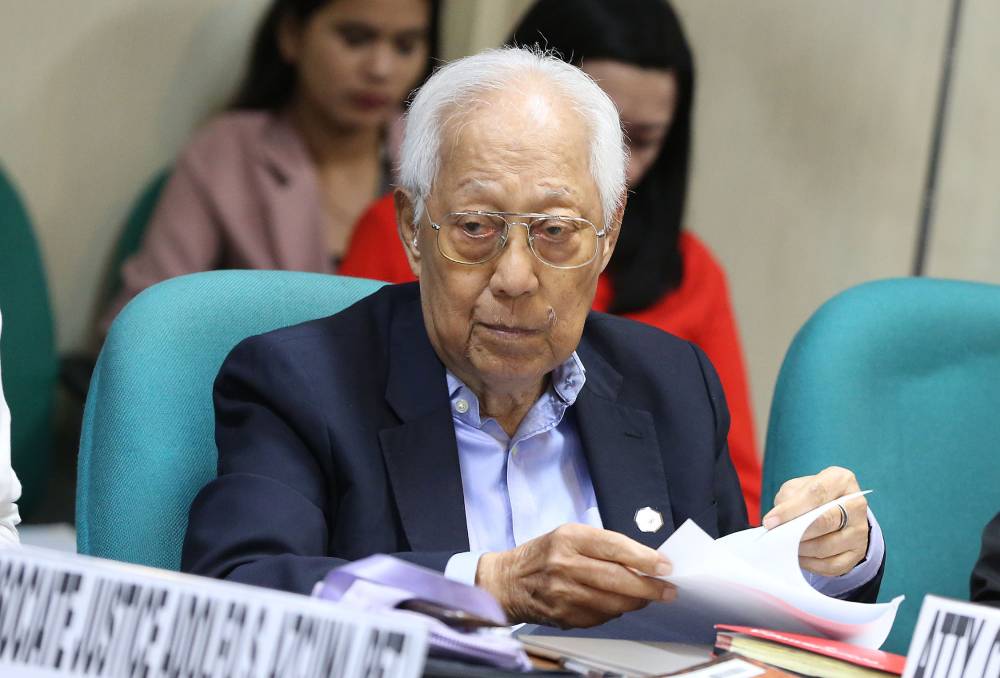

Constitutional expert Christian Monsod on Wednesday called on Congress to pass a law prohibiting a person related to an elected official within the fourth degree of consanguinity or affinity from running for public office—whether in local, national or party list elections.

“I believe that if you look at the intent [of the Constitution] and if also you take what has happened in the past up to now, the political dynasties are so deeply entrenched in our country that we should go for four degrees,” Monsod said at the resumption of the Senate hearing on antidynasty bills.

“From my point of view, every time that’s put to me, my answer is we have already suffered enough from the dynastic tranche so if we’re going to pass a bill, let us pass a bill that totally dismantles this feudalistic system,” he added.

Monsod, one of the framers of the 1987 Constitution, was responding to a question by Sen. Risa Hontiveros about which formulation among the pending bills best reflects the intent of the Charter. Hontiveros chairs the committee on electoral reforms and people’s participation,

Senate Bill Nos. 18 and 1548 filed by Sen. Robin Padilla and Hontiveros, respectively, seek the prohibition of political dynasties with coverage of up to the fourth degree of consanguinity or affinity.

Priority legislation

The fourth degree includes great great grandparents, great aunts and uncles, first cousins, grand nephews and nieces. Based on his 2024 statements of assets, liabilities and net worth, President Marcos has 10 relatives within the fourth degree of consanguinity or affinity who are also elected government officials.

The other bills filed by Senate President Pro Tempore Panfilo Lacson, Sen. Erwin Tulfo, and Sen. Francis Pangilinan seek an electoral ban up to second degree, while the measure filed by Sen. Benigno Paolo Aquino IV explicitly proposes a ban up to third degree.

Political dynasties are banned under Section 26, Article II of the Constitution. Congress has yet to pass an enabling law to enforce it. Antidynasty measures have been filed in nearly every Congress but have never advanced. Both chambers are largely composed of dynasts.

Restrictions, however, exist under Republic Act No. 10742, or the Sangguniang Kabataan Reform Act of 2015. The law prohibits from running for office SK candidates related to officials at all levels of government within the second degree of consanguinity.

In early December, the President directed Senate President Vicente Sotto III and Speaker Faustino Dy III to prioritize bills seeking to end dynasties that have held sway in politics for decades and been blamed for the country’s socio-political and economic ills.

The President specifically identified the Party list System Reform Act; the Independent People’s Commission Act; and the Citizens Access and Disclosure of Expenditures for National Accountability for inclusion in Congress’ list of priority bills.

2nd degree ‘more doable’

The directive came as Mr. Marcos faced the most serious crisis yet stemming from the flood control scandal that saw the ouster of then Senate President Francis Escudero, the resignations of Speaker Martin Romualdez and some Cabinet officials, the creation of a fact-finding body to probe anomalous infrastructure projects, and waves of massive street protests.

The scandal arose from the alleged collusion of lawmakers, public works engineers and private contractors to siphon off billions of pesos in infrastructure projects that turned out to be either substandard or nonexistent.

“If you look at those involved in the corruption scandals, either they are part of a political dynasty or they are related to a political dynasty,” said Akbayan Rep. Percival Cendaña, principal author of House Bill No. 5905 seeking to ban dynasties, along with Akbayan party list colleagues Chel Diokno and Dadah Kiram Ismula, and Dinagat Rep. Arlene “Kaka” Bag-ao.

At the same Senate hearing on Wednesday, retired Supreme Court Associate Justice Adolfo Azcuna said a prohibition up to second degree of consanguinity is more doable.

“The other thing is the [Commission on Elections], we should keep in mind the enforceability of what is approved. As I have said, beyond two degrees, it may be difficult for Comelec to enforce it,” he said, referring to the process of verifying the candidates’ degrees of consanguinity or affinity.

Monsod acknowledged that the prohibition would be better for positions below the national level.

No violation of rights

Addressing concerns that a ban on dynasties would infringe on Filipinos’ fundamental rights, Monsod said: “I don’t think it would go against the fundamental rights of Filipinos. This is just an exception because there is also the need to equalize the opportunity for public service… As I have said, in case of doubt, we have to sustain the choice of the people.”

Hontiveros agreed, saying “It is an attempt to strengthen democracy by making it more open, more competitive, and more fair. Because democracy is not just about being able to vote. It is also about having real choices. We should stop seeing the same family names, families in the ballot.”

In the current 20th Congress, there are at least 21 antipolitical dynasty bills filed in the House of Representatives and six in the Senate. All are pending at the committee level.

In December, following the President’s pronouncement, Dy and Marcos’ son, Majority Leader Ferdinand Alexander Marcos, filed House Bill (HB) No. 6771 which sought to prohibit the establishment and perpetuation of political dynasties.