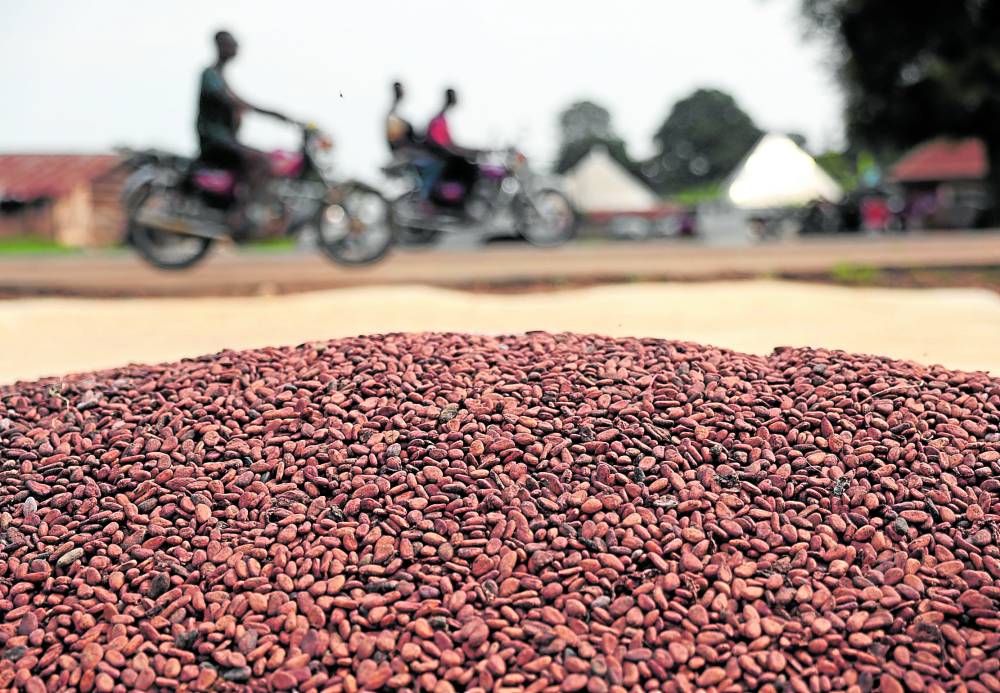

‘Cocoa boys’ flock to Nigerian farmlands, drawn by high prices

IKOM, NIGERIA—Growing up in Nigeria’s cocoa farming area of Ikom in the southeast, Anyoghe Akwa did not see much of a future, so instead he decided to move away, study civil engineering and carve out a career in the construction industry.

That was until 2023, when he heard that cocoa prices were surging and farmers back home in Ikom were making a fortune.

“We saw 20-year-olds who never attended university generating a lot of money from cocoa farming, while those of us who were aspiring for a PhD were struggling,” said Akwa, 47, who had enrolled in a doctorate program.

“So we started to come back and opened our own farms.”

Akwa is one of a cohort of new entrants to the sector, mostly men and nicknamed “cocoa boys,” who have switched to farming or other jobs to cash in on the cocoa price surge.

The Cocoa Farmers Association of Nigeria, which represents smallholder farmers, saw its membership increase by more than 10,000 in 2023-2024.

In Ikom, located in Cross River State on the border with Cameroon, most farmlands are owned by the community. Under an ancestral custom, a person with family roots in the community can present a bottle of wine, an offering of food and a modest sum of around 5,000 naira ($3) to receive a plot of land.

A year’s salary

Akwa had inherited some farmland from his father and added some more through community allocation so he could plant more cacao trees, whose seeds are processed into cocoa and chocolate.

“Last year, I harvested four bags. I sold the first bag for 800,000 naira ($500), and the others between 1 million ($624) and 1.2 million naira ($749) per bag. It was a lot of money,” he said, noting that sale of just one bag matched his annual salary as a civil engineer.

At the top price, Akwa was selling cocoa for 20 times its value in 2022, when the price of one 64-kg bag of beans was 60,000 naira ($37), according to local growers.

Cost of living crisis

A drop in output from Ivory Coast and Ghana, the world’s top two cocoa exporters which together account for 50 percent of global production, drove prices up from $2,200-$2,500 per metric ton in 2022 to nearly $11,000 in December 2024, according to the International Cocoa Organization (Icco), an intergovernmental body.

The price surge coincided with Nigeria’s worst economic crisis in over three decades, with record numbers of people being plunged into poverty.

Those producing cocoa were largely protected, and even helped by a devaluation of the naira that made exports more competitive.

Growers are not the only beneficiaries. The cocoa business also involves factors, or middlemen between farmers and licensed buying agents, who warehouse the beans and sell on to exporters.

Ndubuisi Nwachukwu, 48, made the leap from banker to LBA in 2022, inspired by a business mentor. His timing turned out to be ideal.

Shaking up economy

“The income I’ve made these few years as an LBA, if you add up all the salary I earned as a banker, it is not up to it,” he said.

In Ikom and other cocoa-producing areas, the newly-affluent “cocoa boys” are shaking up local economies and driving up housing costs.

“You can consider me to be a cocoa boy, because when you (talk about) cocoa now, people see you to be a ‘big boy,'” said Mark Bassey, 41, who left a low-paying job as a medical laboratory scientist to become a grower in his ancestral home.

As a boy, Bassey followed his mother to the cocoa plantation, so the skills were familiar to him. Like Akwa, he had wanted something different and had studied science at university, but he found it impossible to make a good wage.

“I know that I will still go back into my profession because of my love for it, but for now I want to focus on farming,” said Bassey, who says he has quadrupled his income.

Smuggling, hedging

Nigeria is the world’s fourth-largest cocoa producer, according to the Icco, but its output of 315,000 metric tons was far behind its West African rivals Ivory Coast and Ghana, at 2,241,000 and 654,000 respectively.

The influx of new farmers, coupled with new cocoa strains that bear fruit within 18 months and government efforts to boost the sector by handing out free seedlings, should be driving up output, but this is not reflected in official statistics.

“Putting all these things together, by now we believe that Nigeria’s cocoa production level would have doubled,” said Rasheed Adedeji, director of research and strategy at the Cocoa Research Institute of Nigeria.

One reason is that a significant proportion of Nigerian cocoa beans, around 200,000 tons a year, are smuggled out of the country, he said.

The CRIN says it has received over half a million requests for new cocoa seedlings so far this year, enough to cover 400,000 hectares of farmland, triple the demand seen in the same period last year.

Still, some of the new growers are hedging their bets. Akwa shuttles between his farm and various construction sites where he still directs teams of workers and foremen.

“I don’t sleep because I have to keep calling them to see if they have done this or that,” he said. But if prices hold, he sees a long-term future in cocoa. “With what I’m seeing, it’s possible that I would switch to cocoa farming full-time.”

Reuters, the news and media division of Thomson Reuters, is the world’s largest multimedia news provider, reaching billions of people worldwide every day. Reuters provides business, financial, national and international news to professionals via desktop terminals, the world's media organizations, industry events and directly to consumers.