Comelec vows to fight digital buying of votes

While the Commission on Elections (Comelec) admits it is difficult to prosecute those involved in vote-buying especially with the advent of digital wallets, it has vowed to go after the perpetrators even if it means circumventing obsolete election laws.

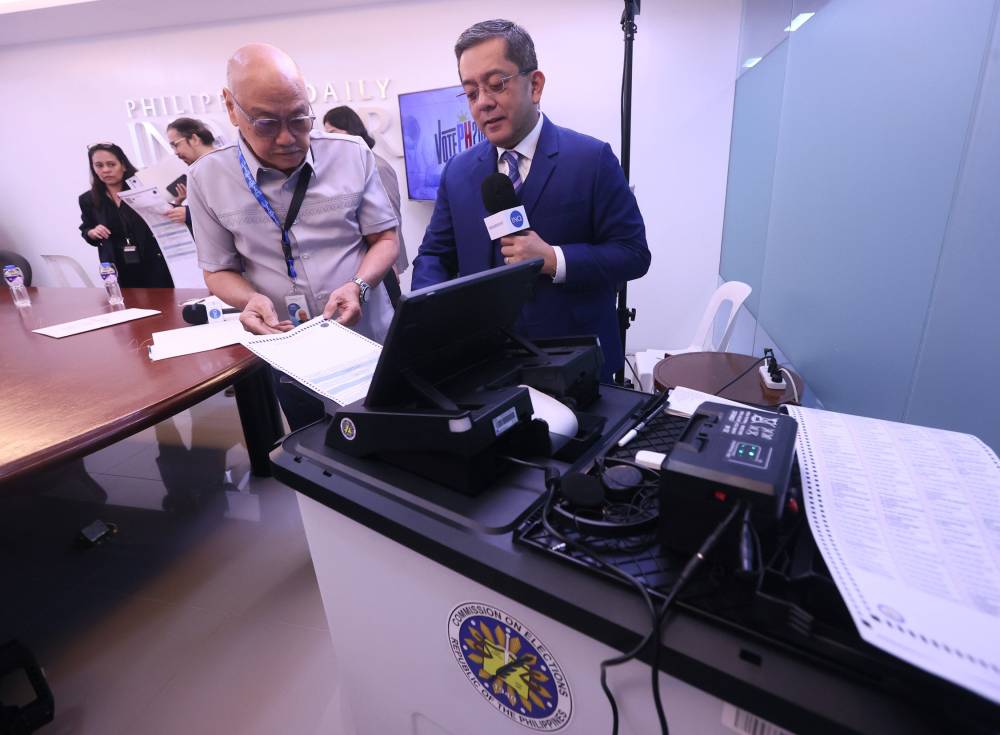

In a recent round-table discussion with journalists from the Philippine Daily Inquirer and Inquirer.net, Comelec Chair George Garcia called vote-buying “the modern cancer of our democracy.”

Vote-buying and vote-selling are prohibited under Section 261(a) of the Omnibus Election Code (OEC), a law enacted in 1985, when mobile payment platforms were not yet available.

Violators can face up to six years in prison while disqualification awaits candidates.

“Our election laws were written for traditional cash handouts, not for GCash and Maya transactions,” Garcia said, adding: “If we don’t act now, digital vote-buying will become even harder to track and punish.”

He said that fortunately, the platforms themselves have imposed restrictions on the daily transaction limit until Election Day or May 12 to help prevent election-related financial misuse.

According to Garcia, they have put in place many actions, which are presumed to be vote-buying and vote-selling.

“We have stated many presumptions which are not in the law and are not considered to be abuse of power,” he said.

“We first implemented them during the 2023 barangay and Sangguniang Kabataan elections, and nobody went to the Supreme Court to question them,” he said.

Presumptions

For instance, people forming long lines to receive goods outside the house of a candidate is presumed to be vote-buying.

Even the mere possession on Election Day of indelible ink or any chemical that can remove indelible ink such as cuticle remover can be presumed an act of vote-buying or vote- selling.

With these safeguards, Garcia said the Comelec was able to file cases against around 7,500 candidates, and prevented 253 winners from being proclaimed, with their cases still pending before courts.

“This is our only way to fight voter-buyers and voter-sellers if there’s still no law prohibiting what they are specifically doing,” he said.

The Comelec also empowered its Kontra Bigay Committee to deter and prosecute not only those who buy and sell their votes but also those who abuse state resources (ASR).

Comelec Resolution No. 11104 defined the offense of ASR as one that “pertains to the misuse of government resources, whether material, human, coercive, regulatory, budgetary, media-related or legislative, for electoral advantage.”

ASR is not explicitly stated in the prohibitions of the OEC, but Garcia said it was “one of the biggest threats in the election that we are fighting against.”

Clear guidelines

He was “personally incensed” that financial aid for the poor are being used to sway voters. He said voters should be angry at politicians who use state resources “like it’s their pocket money” to buy votes.

“We are not against the giving of ayuda (assistance) to our indigent kababayan. We do not want to block these, but we want clear guidelines on how the recipients are selected. And of course, there should be no presence of candidates when giving out these assistance,” Garcia said.

He was particularly dismayed by the failure of the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) to comply with the conditions the Comelec set for exempting its financial assistance programs from a ban on the release, disbursement or expenditure of public funds for social services and housing-related projects 45 days before Election Day—or from March 28 to May 11.

On Jan. 16, the DSWD asked the Comelec to exempt P12.663 billion worth of Ayuda Para sa Kapos ang Kita Program funds from the election spending ban. This was on top of the P882 million for 27 social programs earlier exempted “conditionally” by the poll body.

“It is almost two months and I have not yet approved their exemption request because I am still waiting for the guidelines for their first exemption. I told the DSWD, ‘Why should I grant a second exemption if you have not submitted the guidelines first?’” Garcia said.