Covering FVR: Grueling, surprising, fun

If I were to describe how it was covering Malacañang during the presidency of Fidel V. Ramos, I would say it was grueling but still fun.

At an average of once a week, Ramos would visit a province to make a speech and hold meetings with local officials. Our day as members of the Malacañang Press Corps (MPC) started at 4 a.m. at Villamor Air Base, to get on board an Air Force Fokker plane that would fly us to a province, then travel by land or Huey helicopter to the remote area Ramos was visiting.

We would listen to his speech and try to interview either him or his officials after, then file a story using a slow dial-up connection or by fax, then fly back to Manila in the afternoon.

On other days, our coverage involved listening to Ramos give a speech in Malacañang or some venue in Metro Manila, or spending hours waiting for a chance interview with officials going into or coming out of meetings with the Chief Executive.

Dressing-down

There were times we would be in Malacañang at 6 a.m. on a weekend because Ramos was going to play golf at Malacañang Park, and we hoped we could catch him before he teed off. It always paid off for us: He would oblige us bleary-eyed reporters and answer one or two questions, probably feeling sorry that we had to be up so early just to get a story.

Ramos had a great relationship with the MPC. When his presidential term was about to end, I interviewed his close-in aides and learned that he always checked whether the journalists covering him in his out-of-town events had had their lunch. (It was usually a packed lunch of rice and adobo or fried chicken in a styrofoam container.)

On one occasion, I witnessed the President dressing down a press undersecretary. Years later, I learned that it was because Ramos found out that the reporters covering him in that trip to Baguio had not had their lunch yet, and it was almost 2 p.m.

But he could strike terror, too, in the hearts of journalists who, like me, were scared of asking questions during his weekly televised press conference. Ramos would sometimes show annoyance at questions from journalists, but I was fortunate that this never happened to me.

After Ramos’ term, I asked one of his aides whether there was a particular reporter the President did not like. The aide’s answer surprised me: It was a male reporter from a major TV network.

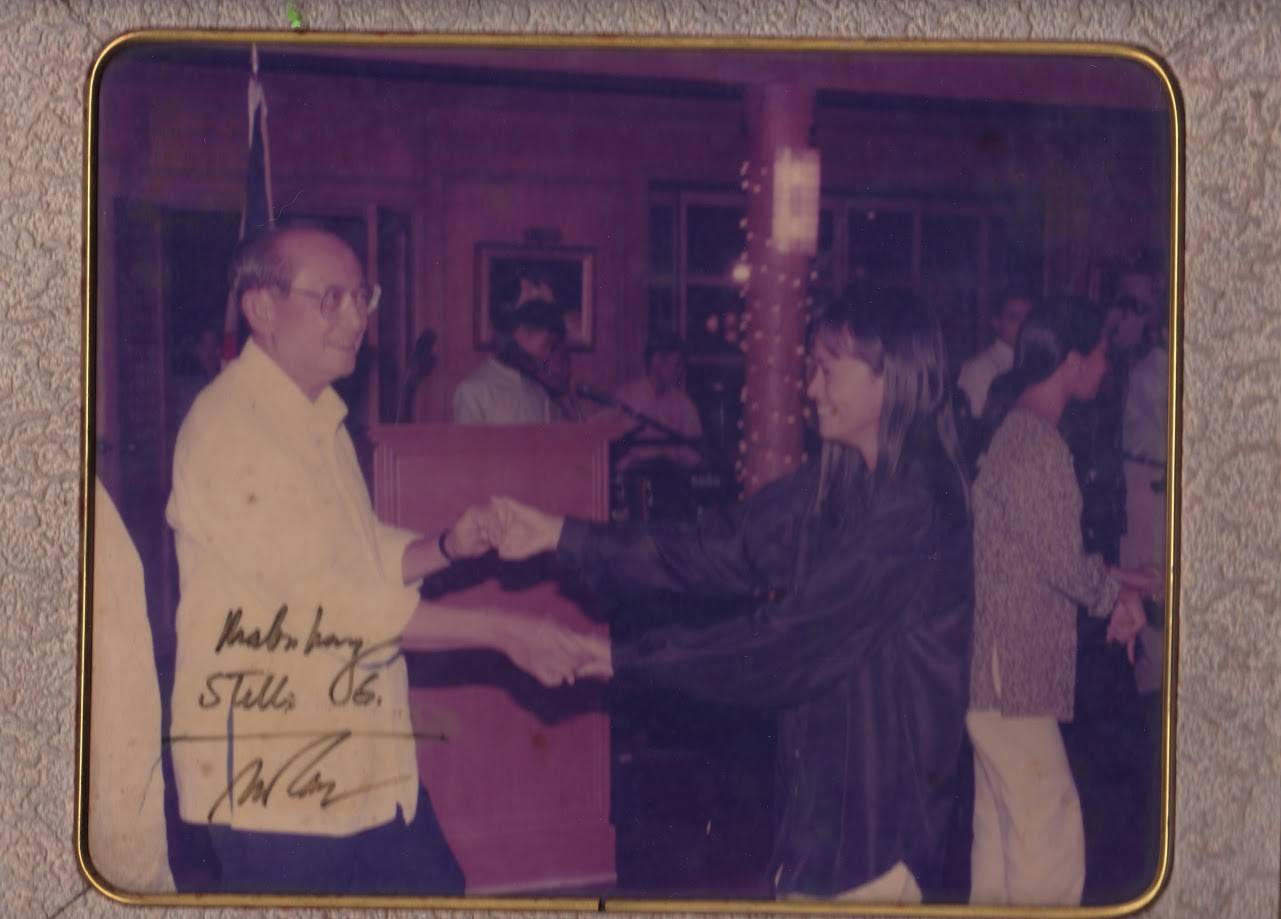

“Ambush” interviews were indispensable to our work. We could ask any question we wanted, and it was up to Ramos if he wanted to answer directly or in a roundabout way. One trick was to ask the question in a nice, nonconfrontational, way; you were likely to get an answer that would be good enough for a story. Another was not to catch him unprepared; it was not unusual for reporters to send a note to his aides asking if we could interview the President after an event. Once cleared with Ramos, we would then get a slight nod from the aide, meaning yes, he was willing to be interviewed. But at times, it would be a shake of the head.

It was a cordial relationship between the President and the journalists covering him, honed over the years when he was still defense secretary.

Meeting protesters

One unforgettable coverage for me was when Ramos met a small group of farmers holding a rally outside the then Philippine Plaza hotel. He had just finished his keynote speech at a gathering inside the hotel, had boarded his car, and was on his way back to Malacañang.

We followed the presidential convoy in Palace press vehicles. But upon reaching the end of the driveway, his car stopped and Ramos got off and walked toward the group of angry, shouting farmers. Stunned, we managed to rush out of our vehicles to cover what was happening. Members of the Presidential Security Group (PSG) were alarmed, but what could they do if their boss wanted to speak to the protesters?

Even the protesters were surprised. Ramos spoke to them and asked about a well-known farmer-leader. Their angry reply to him was: “Wala na siya sa amin” (He’s not with our group anymore). The exchange lasted a few minutes, then Ramos went back to his car.

The protesters later released a statement contradicting accounts of what had happened. I wrote a story that included the farmers’ version of the encounter, but I made sure to add what we journalists had witnessed. The following day, someone from the President’s staff showed me a clipping of my story with a marginal note written by Ramos: The president said it was an accurate account of what had taken place.

Hands-on president

There was also the time when Inquirer reporter Martin Marfil, who was assigned with me at Malacañang, covered an event in Tondo. In the middle of Ramos’ speech, members of the audience started throwing chairs at each other. The PSG were visibly worried, but Ramos was unfazed by the melee.

Covering a hands-on president was not easy. When Supertyphoon “Rosing” hit the Philippines in 1995, Ramos went to Camp Aguinaldo to personally monitor reports and disaster response operations. He was annoyed when he learned that some government officials were not in their offices. He stayed there for hours; clearly, it was not just for show, unlike other leaders who only made sure the cameras captured their presence before leaving.

After Camp Aguinaldo, we followed Ramos’ convoy back to Malacañang, thinking we already had our story for the day. But then the president decided to head off to Smokey Mountain, the landfill in Tondo, to personally check the situation there.

We tailed his car to Tondo as strong winds howled outside our press vehicles. The reporters were all hoping that the road to Smokey Mountain was closed, or we would have to risk safety and cover the president once he got off his vehicle and inspected the area. Our prayers were answered: By the time we reached the North Harbor area, the presidential car and the PSG escorts had to turn right on Moriones street instead of proceeding further north on R10, since the road to Smokey Mountain was now impassable.

Keep digging

We would have missed out on these and other stories if we did not follow Ramos everywhere he went and just relied on press releases. Journalists are not supposed to be just receptacles of information (or disinformation) dished out by government officials; we owe it to our readers, listeners, or viewers to keep digging, even if that meant waking up in the middle of the night for coverage early the next morning, or working very late in case something unexpected happened.

We were fortunate that Ramos appreciated the role of a free press in a democratic society. This military man was one who respected the Fourth Estate. INQ

The writer is an editor at the Financial Times in London.