Disputed Boracay Ati land barricaded amid legal battle

ILOILO CITY — Members of the Ati community in Boracay Island, Malay, Aklan, were stunned to find a portion of the land they have been cultivating barricaded by private developers, despite ongoing legal battles to protect land awarded to them years ago.

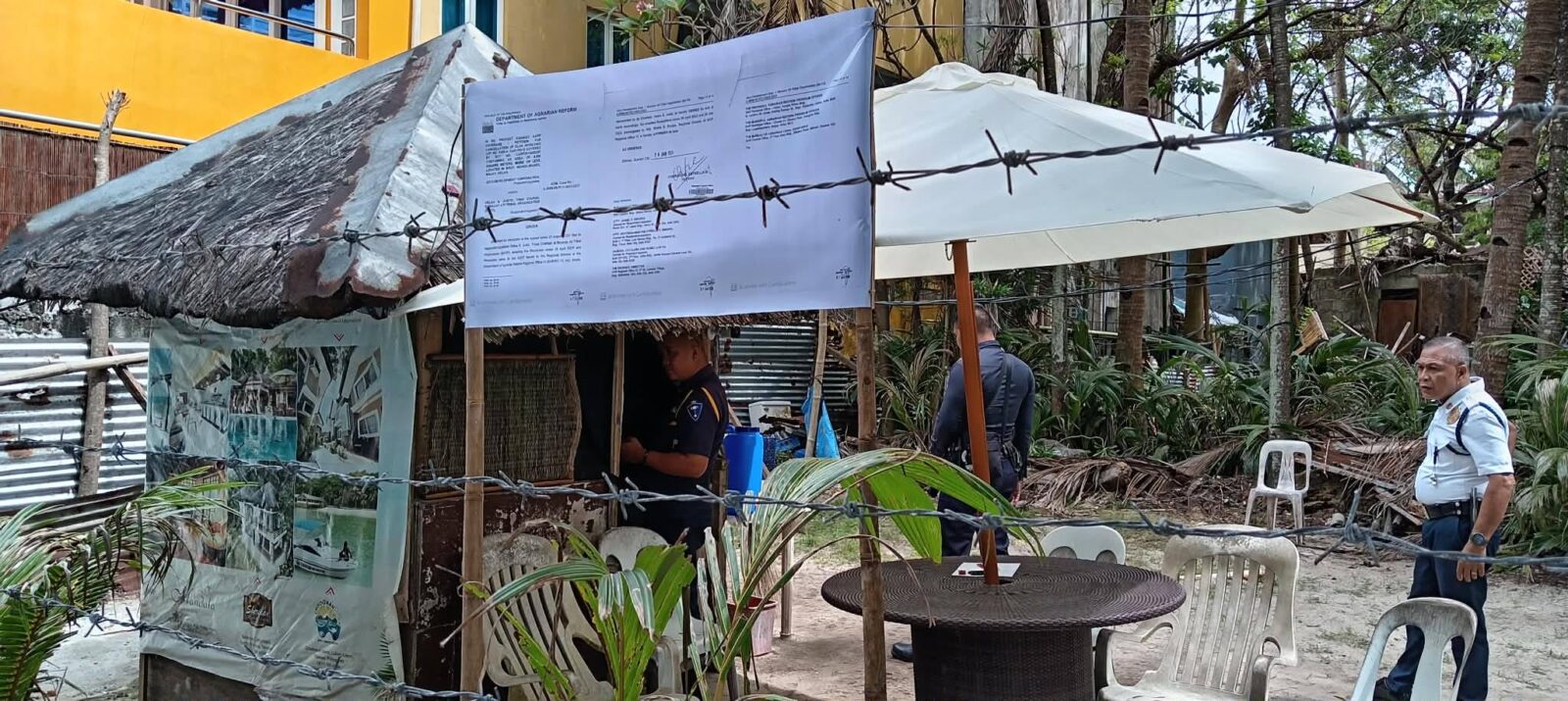

The Asosasyon Boracay Ati Tribal Organization (ABATO) said they discovered the area cordoned off with wire and wood early Monday morning at Station 3, with a locked gate preventing entry.

“Earlier at 8:30 a.m., we were shocked to find a sturdy barricade blocking our land. Boracay Atis could not enter,” ABATO said in a statement.

The disputed site is part of five parcels granted by the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) in 2018 under the Duterte administration through Certificates of Land Ownership Award (CLOAs).

The barricade included a large tarpaulin displaying a copy of a Notice of Order from the DAR dated Jan. 29, 2024, which was certified as a true copy only on Jan. 7 this year.

Signed by DAR Secretary Conrado Estrella III, the order affirmed a regional resolution canceling one of the granted CLOAs, with Jeco Development Corporation listed as protestant.

Rejected proposal

In 2024, Estrella assured ABATO that alternative government land would be provided, but the group rejected the proposal, saying the suggested parcels were in Antique province, far from Boracay.

The barricade was put up despite no Notice to Vacate or Writ of Execution having been issued — documents normally required to enforce such orders.

“This incident is a continued violation of our rights, and we believe that the ‘rule of law’ is not being followed,” ABATO said in its Facebook post.

Maria Tamboon, one of ABATO’s leaders, told the Inquirer that they only received a copy of the Notice of Order on Jan. 23. Alongside nuns assisting the community, they visited the site to clarify the status.

“We explained that it was only a Notice [of Order] and not final. Nothing should have happened yet. But our gardener informed us that the land was inaccessible, so we went there with two sisters to clarify, because we had not received finality from DAR,” Tamboon said.

She added that the developers’ security personnel should have waited for the DAR to serve the final documents before blocking access.

“Who enforces the order should be the DAR, not security guards. Why are they leading and acting as law? They should just wait for the courts,” she said, adding that they warned of legal action against the guards, who had concealed their identities.

Following legal advice, ABATO members took photos and filed a police blotter.

Tamboon noted that CLOA 5, the affected area, contains gardens where Ati families grow bananas, cassava, tubers, papaya, and coconuts. Earnings from these crops, ranging from P 500 to P 1,000 per harvest, support their daily sustenance.

Workers passing through the disputed land are reportedly allowed access, though Tamboon said, “There’s some discrimination against us there.”

Lawyer Daniel Dinopol, who represents ABATO alongside his daughter Kchyrziahshayne Dyñelle, said the case is the subject of a motion for reconsideration filed via courier on Feb. 4, within the 15-day period allowed by DAR. Tracking confirms it was received on Feb. 9 by an employee named Russel Rosvelio.

Dinopol reiterated that ABATO intends to contest the CLOA cancellations through all available legal channels, including the Supreme Court if necessary.

A similar 2023 case, in which the DAR regional office granted cancellation in favor of Anchor Land president Digna Ventura, was affirmed by the Office of the President — prompting ABATO to file a motion for reconsideration.