Enrile dies at 101: From martial law to Marcos 2.0

Juan Ponce Enrile, one of the country’s most enduring political figures of the 20th and 21st centuries, has died, leaving an indelible influence on the country’s politics bookended by the rise and fall of his mentor, Ferdinand Marcos Sr., and the ascension to Malacañang of the dictator’s son and namesake. He was 101.

“It is with profound love and gratitude that my father, Juan Ponce Enrile, peacefully returned to his Creator on November 13, 2025, at 4:21 p.m., surrounded by our family in the comfort of our home,” Enrile’s daughter, Katrina, said in a statement.

“It was his heartfelt wish to take his final rest at home, with his family by his side. We were blessed to honor that wish and to be with him in those sacred final moments.”

Enrile’s family asked for privacy while they grieve and honor his memory.

Enrile is survived by his wife, Cristina Castañer, their two children Jack and Katrina, eight grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

Controversial legacy

President Marcos said Enrile, whom he fondly calls “Tito Johnny” and whom others call “Manong Johnny,” was “one of the most enduring and respected public servants our country has ever known.”

“For over 50 years, Juan Ponce Enrile dedicated his life to serving the Filipino people, helping guide the country through some of its most challenging and defining moments,” he said.

According to the President, Enrile, his presidential legal counsel, remained brilliant, sharp, and firm in the belief that law and governance must always serve the Filipino people until his final years.

Enrile left behind a controversial political legacy—one that involved scheming and shifting allegiances for survival—that historians, political scientists and the public alike will continue to dissect for years to come.

Sheer longevity gave him time to whitewash his dark side—from being the architect of the Marcosian martial law, to a leader who helped oust the dictatorship that he was partly responsible for, and to eventually the sharp-witted politician later in his career.

Having been one of the longest and oldest serving politicians in the Philippines, Enrile outlived many of his peers in politics, including ex-Presidents Marcos Sr., Diosdado Macapagal, Corazon Aquino, Fidel Ramos and Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III.

He had lived long enough to be exonerated of all the plunder and graft charges in the alleged diversion of P178 million of his Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF) in the P10-billion pork barrel scandal.

In handpicking Enrile to be among his closest aides, Mr. Marcos was seen making an extraordinary act of reconciliation with one of the central figures in the downfall of the Marcos family during the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution.

“I will devote my time and knowledge for the republic and for BBM (Bongbong Marcos) because I want him to succeed,” said Enrile, who was 98 when he was appointed to his last government post in 2022.

On Enrile’s 101st birthday on Feb. 14, the President called him a “statesman, a legal luminary and an exemplary public servant” who not only witnessed history, but also actively shaped it.

Humble roots, key roles

“In that time, he has amassed a wealth of wisdom and experience, which he generously shares. It is one that all presidents, including myself, have gladly partaken in,” Mr. Marcos said.

Born on Feb. 14, 1924, in Gonzaga, Cagayan, Enrile rose from humble beginnings to become a lawyer, government officer and key actor in pivotal moments in the nation’s history.

He graduated cum laude in 1949 with an Associate of Arts degree from the Ateneo de Manila University. He earned his law degree, cum laude, from the University of the Philippines in 1953, became a member of the Philippine Bar in 1954, ranking No. 11 in the bar exams.

He obtained his Master of Laws degree from Harvard University in 1955, taught law at the Far Eastern University and joined his father’s law firm before taking responsibility over the personal legal affairs of then Senator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. in 1964.

After Marcos Sr. was elected president in 1965, Enrile became his protégé and part of his inner circle. Enrile served as customs commissioner and interim finance secretary from 1968 to 1970.

He lost in the 1971 senatorial election and was appointed defense secretary by Marcos Sr. a year later. He took on the role of martial law administrator until he broke away from the dictator in February 1986.

Marcos Sr. imposed martial law with his Proclamation 1081, saying that he was prompted to declare it immediately after communist rebels allegedly ambushed Enrile on Sept. 22, 1972.

In several interviews leading to the 1986 uprising, Enrile admitted that the attack never took place. But in his 2012 memoir, he flip-flopped and accused his political opponents of spreading rumors that the ambush was staged.

The martial law period was among the darkest in the country’s history, marked by brutality and human rights violations and the deaths of more than 3,000 people. Congress was padlocked, media was muffled and the political rivals and opponents of Marcos Sr. were jailed while 34,000 were tortured by the military and police.

By the end of the Marcos regime in 1986, an estimated $5 billion to $10 billion of ill-gotten wealth were believed plundered by the Marcoses during their two decades in Malacañang.

While in the Marcos Cabinet from 1978 to 1984, Enrile also served as assemblyman in the Interim Batasang Pambansa.

Breakaway

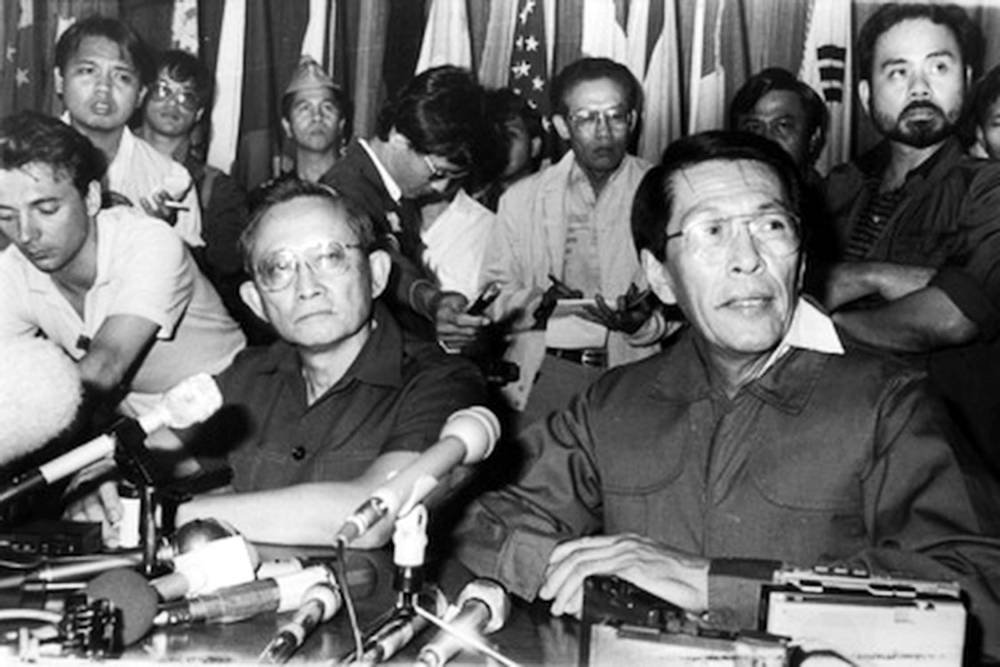

Along with then Philippine Constabulary chief Fidel Ramos, Enrile broke with Marcos, turning against the dictatorship, playing a pivotal role in the Edsa Revolution that installed Corazon Aquino as president.

But tensions between Enrile, who continued on as defense secretary, and Aquino surfaced early in her term, leading to his dismissal from the Cabinet in late 1986 after he was linked to a coup plot.

After leaving the Aquino Cabinet, Enrile was elected as a lawmaker. He served four terms in the Senate for a total of 23 years, one of the longest senatorial tenures in the Philippines.

During his first term in the Senate in 1987-1992, Enrile served as the lone minority.

He then served for one term as Cagayan 1st District representative from 1992 to 1995, before running again for the Senate where he served more than two decades.

Among the laws that he authored were Republic Act No. 8424, or the Comprehensive Tax Reform Act, which exempted overseas Filipino workers from paying income taxes in the Philippines on their income earned abroad.

He was Senate President during the 14th and 15th Congress, from November 2008 until he stepped down from the post in June 2013. He remained a senator and the minority leader until 2016.

Legislation

It was under Enrile’s leadership that the Senate passed vital pieces of legislation such as the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program Extension with Reforms (Carper Act), Anti Torture Act, Expanded Senior Citizens Act, Anti-Child Pornography Act, National Heritage Conservation Act and Real Estate Investment Act.

As Senate President, Enrile presided over the impeachment court that tried and convicted then Chief Justice Renato Corona for failing to fully disclose his statement of assets, liabilities and net worth, becoming the first high official to be convicted and removed from office through impeachment.

Enrile had his own political and legal problems after being linked to mutinous soldiers, particularly members of the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM), which were led by one of his top aides, Gregorio Honasan II, who later became a senator himself.

In February 1990, Enrile was charged with “rebellion complexed with murder” for his alleged participation in the deadliest coup against Aquino in December 1989.

Another rebellion charge

He was allowed to post bail by the Supreme Court a week later. The court invalidated the rebellion charges against him in June the same year.

In May 2001, Enrile was again charged with rebellion, in connection with an alleged coup plot against then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. He was arrested for allegedly masterminding the violent siege of Malacañang on May 1 by demonstrators loyal to deposed President Joseph Estrada.

But only a few days after the arrest, the high tribunal ordered the police to release Enrile on a P100,000 bail. Government prosecutors opposed his bail on grounds that rebellion was a capital offense, but the court ruled that the evidence against Enrile was hearsay.

Pork barrel scam

More than a decade later, in 2013, following the Inquirer’s exposure of the P10-billion pork barrel scam, investigations led to indictments of some lawmakers, including Enrile.

In June 2014, the Office of the Ombudsman filed separate criminal charges against Enrile and his fellow Senators Ramon “Bong” Revilla Jr. and Jinggoy Estrada for plunder and multiple counts of graft in connection with the pork barrel scam. Weeks later, the Sandiganbayan ordered their arrest.

Enrile, along with his former chief of staff Gigi Reyes and alleged pork barrel scam mastermind, Janet Lim Napoles, allegedly pocketed more than P172 million in kickbacks from his PDAF from 2004 to 2010.

He was detained at the Philippine National Police General Hospital while Estrada and Revilla were held at the PNP Custodial Center in Camp Crame.

Citing his advanced age and poor health, the Supreme Court granted bail to Enrile in August 2015.

He was acquitted of plunder but remained charged with 15 counts of graft. Enrile was last seen by the public on Oct. 24, 2025, when he briefly appeared via Zoom looking frail on a hospital bed with a tube inserted in his nose as the Sandiganbayan ruling absolving him of the graft charge was read.

Social media presence

In recent months, Enrile was busy on social media, sending birthday greetings, sharing his favorite poems and making political commentaries.

His posts gained traction when he defended the Marcos administration’s decision to surrender former President Rodrigo Duterte to the International Criminal Court through the International Criminal Police Organization (Interpol) and criticized the bloody war on drugs.

The last time Enrile posted on his Facebook page, he was musing on the Sept. 21 anticorruption protests, comparing it to the French Revolution and executions by the guillotine.

Enrile had not only managed to physically survive, but also resurrect his political career several times, enduring losses in the 1998 presidential election and the 2001 and 2019 senatorial races, only to return to the national stage as the legal adviser to the son of his mentor.

Stem cell—and ‘saluyot’

Over the years, he would tell journalists the “secret” to his long life—eating “saluyot,” exercising regularly and undergoing stem cell therapy.

Medical anthropologist and former Inquirer columnist Gideon Lasco encapsulated Enrile’s over a century on earth: “The very fact that he is far more known for immortality than for impunity speaks of the redemptive value of longevity itself. In Philippine politics, to add to a much-used line from Harvey Dent: Either you die a hero, live long enough to see yourself become the villain—or live even longer and become a Juan Ponce Enrile.”