Front-of-pack food labels pushed amid rise in chronic kidney disease

(Last of two parts)

Reynaldo Abacan of Meycauayan, Bulacan province, was only 20 years old when he was diagnosed with stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD5).

At 36, he has been undergoing four-hour dialysis sessions thrice a week for the past 15 years.

Aside from his damaged kidneys, he also developed a wide variety of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), including those affecting his heart, liver, and parathyroid.

His doctors told him that his kidneys were already weak when he was born, but his lifestyle growing up worsened his condition.

“When I was a busy college student, I loved instant foods. My go-to meals were junk food, and soft drinks were my water. I did not know that was bad, because my friends were eating and drinking the same,” he told the Inquirer after getting his government-provided maintenance medicines at the Philippine Heart Center in Quezon City.

In 2016, he founded Dialysis PH, an online-based patient support group to help fellow patients get more information about their kidney disease and know where they could seek government-provided benefits.

From mere hundreds, the group’s membership has grown to 83,000 in 2025. But Abacan was shocked and heartbroken to learn that many of their members were young Filipinos.

“When I was starting my dialysis sessions, I shared the beds with elderly patients. They were asleep most of the time. But recently, my dialysis-mates were all younger than me,” he shared.

Among the group members, he found children as young as 12 who had developed CKD due to poor eating habits.

“Their parents did not know the harm that processed food could do to their children,” Abacan said. “It would have helped not only us CKD patients, but also still healthy Filipinos, to warn us of foods that we should avoid because they are unhealthy.”

President’s order

President Marcos expressed concern upon learning of the large number of young patients getting hemodialysis sessions, including those diagnosed with CKD, when he visited the National Kidney and Transplant Institute (NKTI) in Quezon City last June.

Mr. Marcos ordered the Department of Health (DOH) to develop a CKD prevention program that will address the root cause of the disease.

“Most of our CKD cases today are due to diabetes and hypertension. That is why the President instructed me to strengthen our primary care prevention,” Health Secretary Teodoro Herbosa said.

He also stressed the importance of introducing Filipinos to healthy eating habits at an early age, as a long-term solution to lowering the incidence of NCDs such as heart diseases, cancers, diabetes, and CKD.

Higher prevalence

While CKD is a global public health concern, it should be a more urgent issue in the Philippines, since Filipinos are three times more likely to develop CKD throughout their lifetimes compared with other nationalities.

According to the NKTI, the prevalence of CKD in the Philippines is at 35.94 percent, much higher than the global estimates pegged between 9.1 percent and 13.4 percent.

According to a report from the World Health Organization (WHO), kidney diseases are the fourth leading cause of death in the Philippines, following ischemic heart disease, stroke, and lower respiratory infections.

The Philippines also has the most number of deaths due to renal failure in Southeast Asia.

For every 100,000 Filipinos who died in 2021, 35 were due to kidney diseases—sharing the spot with COVID-19 at the height of the pandemic.

The WHO considers NCDs as “silent killers,” causing 75 percent of all global deaths per year and often affecting individuals before they realize they are at risk.

People who have unhealthy diets are physically inactive, and those who smoke and consume alcohol are more at risk of developing NCDs.

Nutrition labeling

To address this problem, global organizations such as the WHO, Food and Agriculture Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, and the Pan American Health Organization have been urging governments since 2019 to implement nutrition labeling, specifically “front-of-pack labeling” (FOPL), as one of the interventions to reduce unhealthy diets and lower the intake of sugar, sodium, and fats.

FOPL is simplified nutrition information on the front of food packaging in addition to the mandatory nutrition labeling usually put at the back of food products.

The WHO noted that food labeling policies alone “have the potential to reduce the prevalence and incidence of a range of NCDs by as much as 5 percent.”

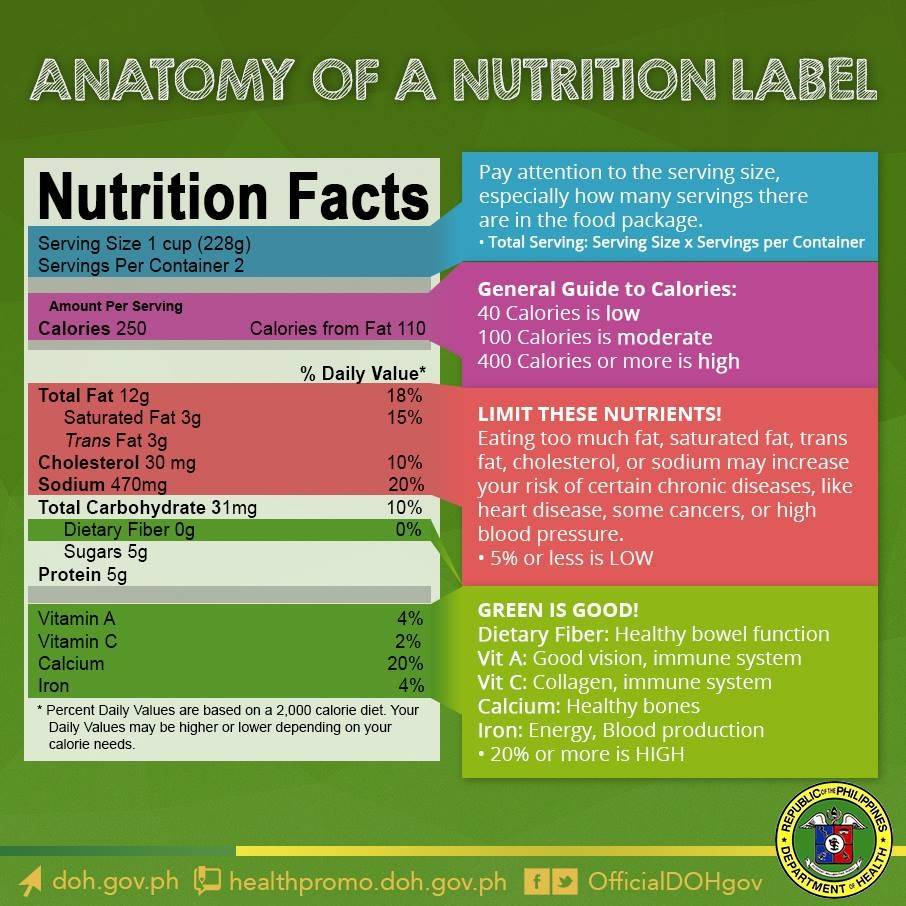

The Philippines currently implements a mandatory back-of-pack label on prepackaged food products, including a complete list of ingredients, allergen information, and a nutrition facts table in compliance with DOH Administrative Order No. 2014-030.

Endorsement logos, particularly the “Sangkap Pinoy Seal,” are also implemented to identify food products that have been fortified with iodine, iron, and Vitamin A.

Through Food and Drug Administration Circular No. 2012-015, food manufacturers are also directed to “voluntarily declare” the calorie content of their products through fopl or signs “to heighten awareness of consumers on [the] energy content of the products.”

Inadequate policies

But government agencies, lawmakers, and health advocates say these measures are not enough. They are pushing for mandatory front-of-pack labeling in foods, to make such information easier seen and understood by Filipino consumers.

Carl Vincent Abanilla, senior science research specialist of the Department of Science and Technology-Food and Nutrition Research Institute, said their studies found that “only 14 percent of Filipino consumers are looking at nutrition facts. What they are looking for on their food packages are the date of expiration, followed by the brand, and then the price.”

“Nutrition facts, which should have helped consumers make informed food choices by looking at the key nutrient values, come only at fourth,” Abanilla told the Inquirer, adding that consumers ignore nutrition facts because they find the information too technical, too small to be read, or placed at a less readily accessible spot in the food packaging.

The country also has yet to adopt an appropriate Nutrient Profile Model (NPM), which determines and sets nutrient thresholds—particularly the amount of sugars, fats and salt—across different product categories.

The NPM can become a tool to guide policymakers in implementing regulatory measures on processed foods, including in terms of taxation, FOPL, marketing restrictions, school food regulation, and public procurement.

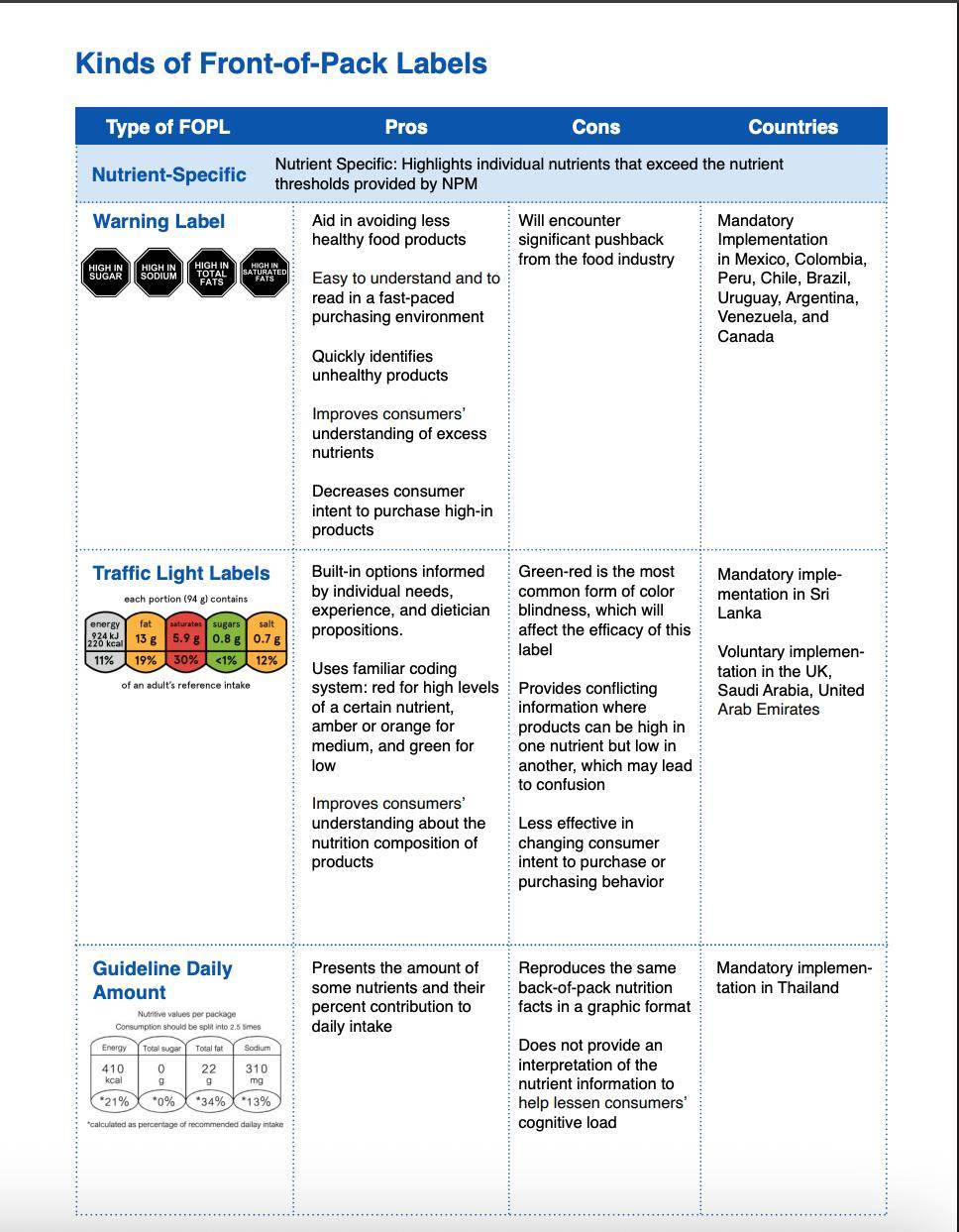

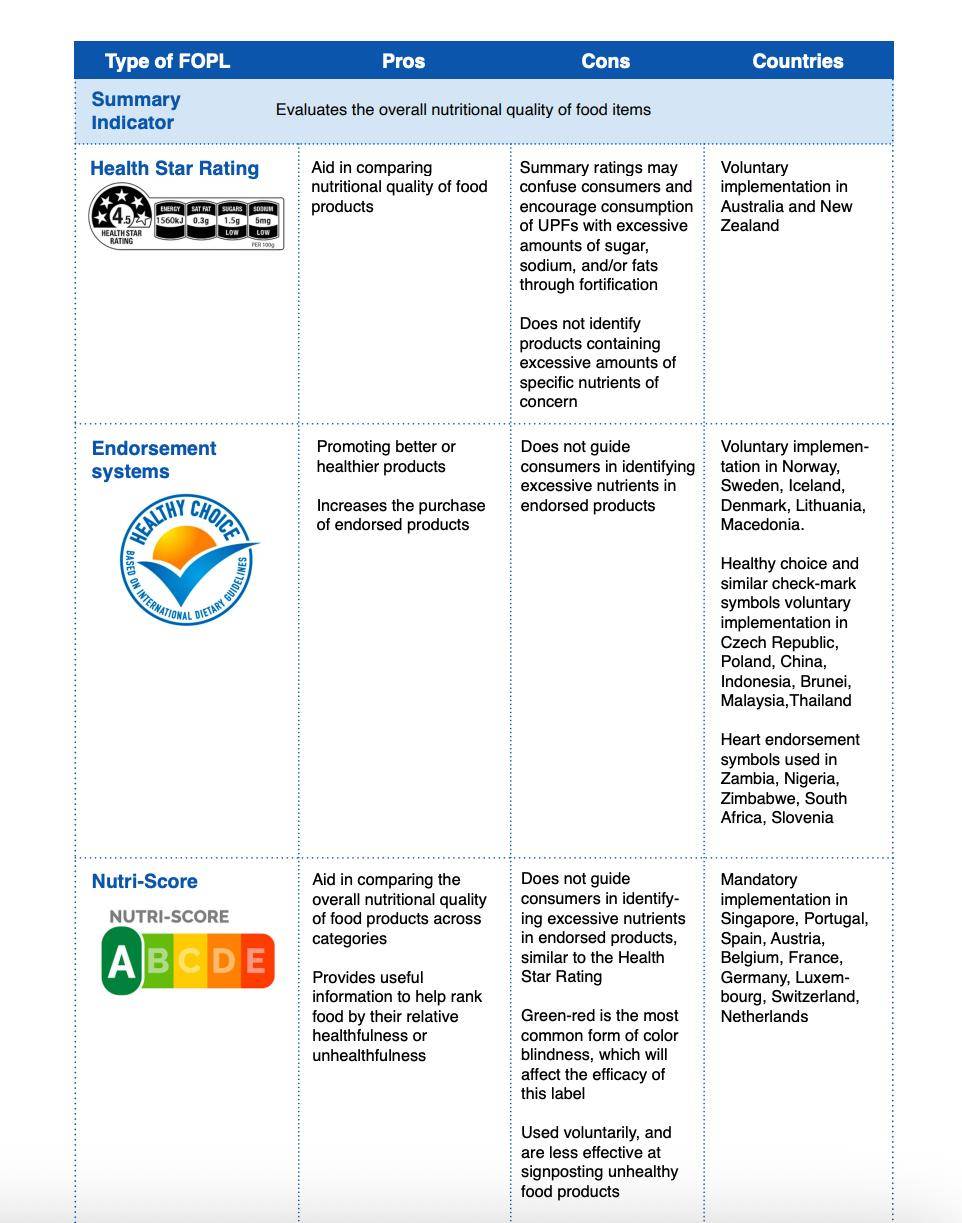

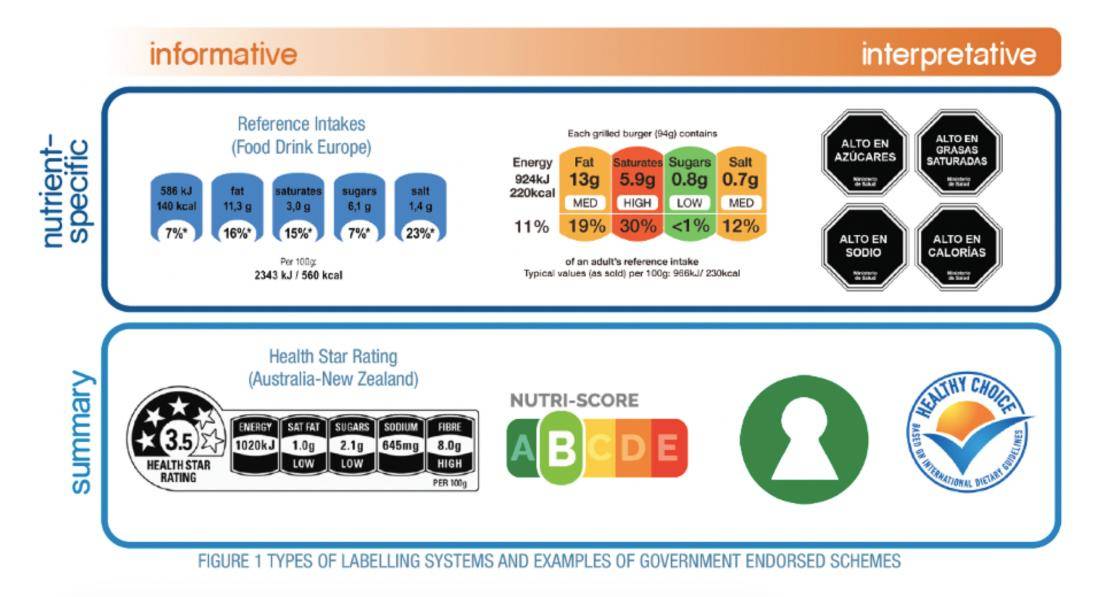

FOPL systems are broadly categorized as either informative or interpretative, depending on the level of interpretation the label provides. (See the table of front-of-pack labels on this page.)

“We first have to determine the characteristics of our population who will be affected by the FOPL. Only then can we find the best possible communication channel to be used in implementing an FOPL policy in the Philippines,” Abanilla said.

Languishing bills

Several lawmakers pushed for FOPL in the 19th Congress, with many seeking mandatory warning labels for food products high in fat, sodium, and sugar, and stricter measures for marketing these food products to children.

However, these bills languished at the committee level, without even being introduced to the floor on second reading.

In the current 20th Congress, FOPL policy is not among the priority bills of the Marcos administration. Still, at least 15 bills have been filed, all except one by House lawmakers, rehashing provisions from their previously filed legislation.

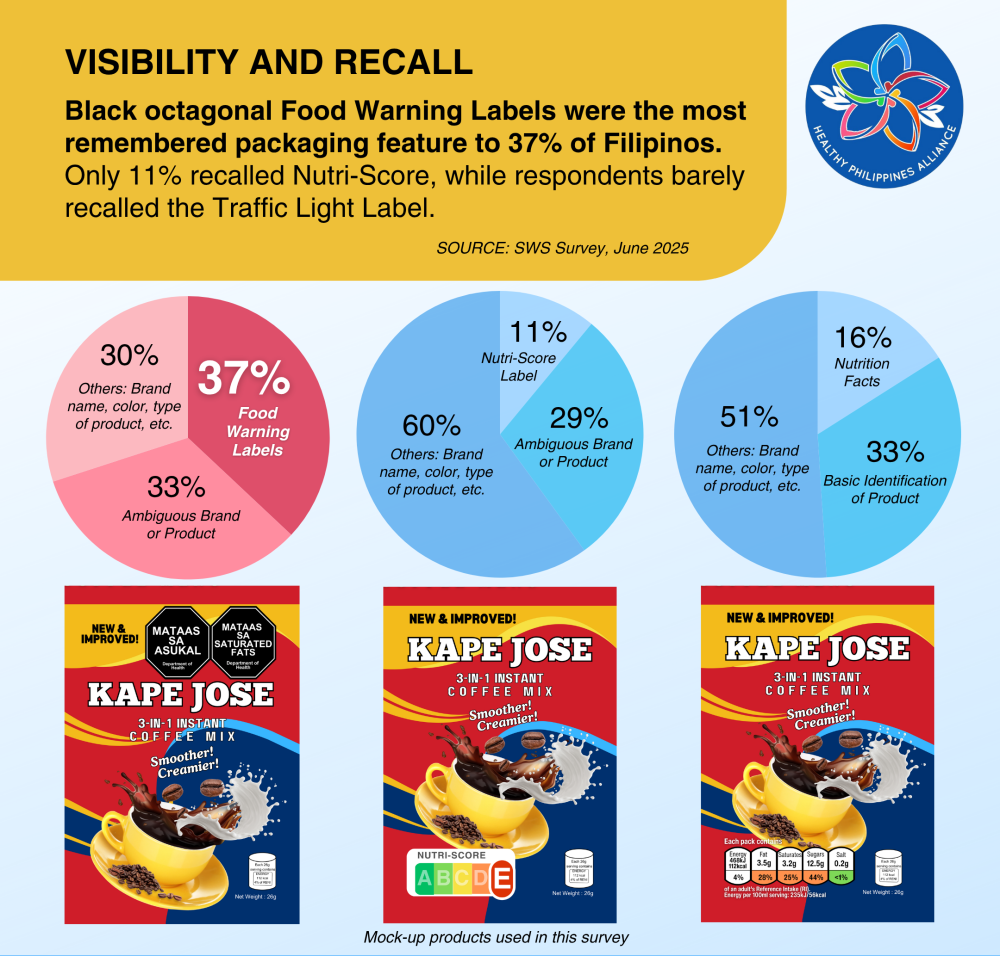

While the government has yet to decide on which type of FOPL is best suited for the country, the Healthy Philippines Alliance (HPA), a network of public health advocates committed to prevent NCDs, is pushing for black octagonal food warning labels in products.

Based on its commissioned surveys and focus group discussions with parents, the HPA said food warning labels explicitly saying a product is high in sugar, unhealthy fats, and salt are the most effective front-of-pack labeling scheme to address Filipinos’ unhealthy consumption of ultra-processed food.

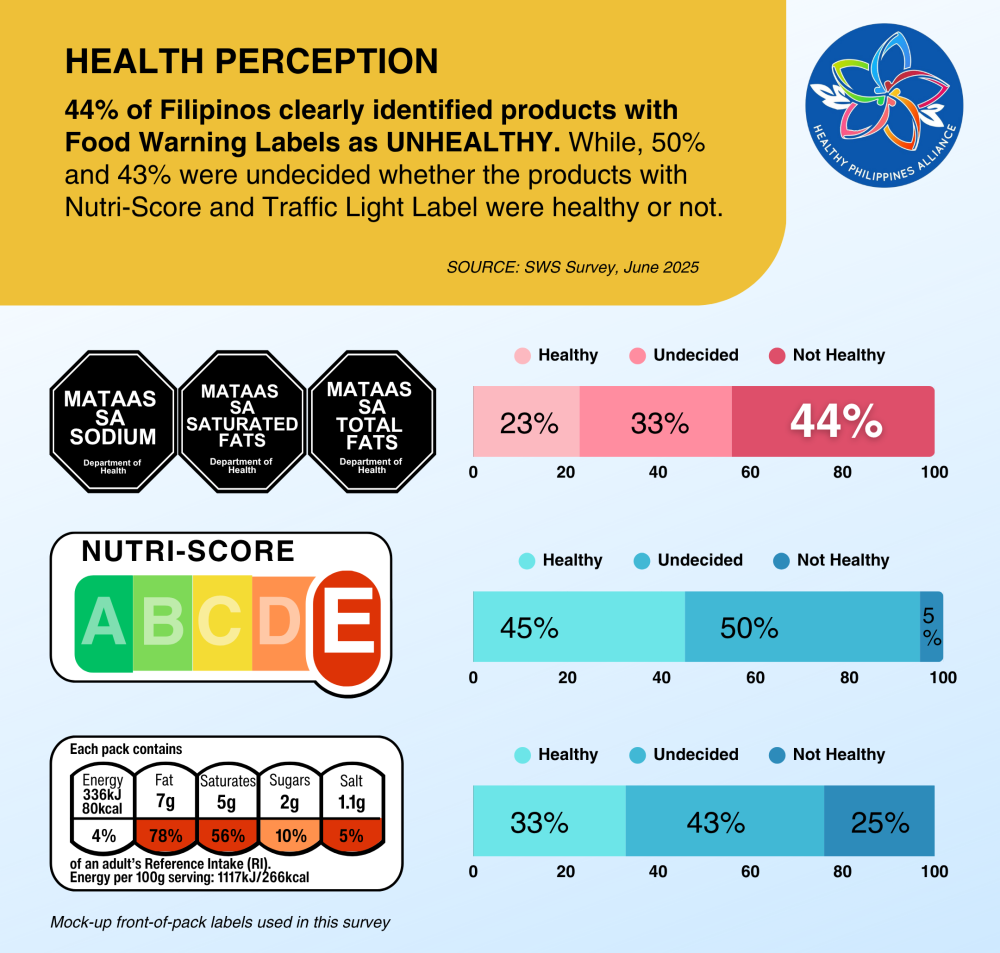

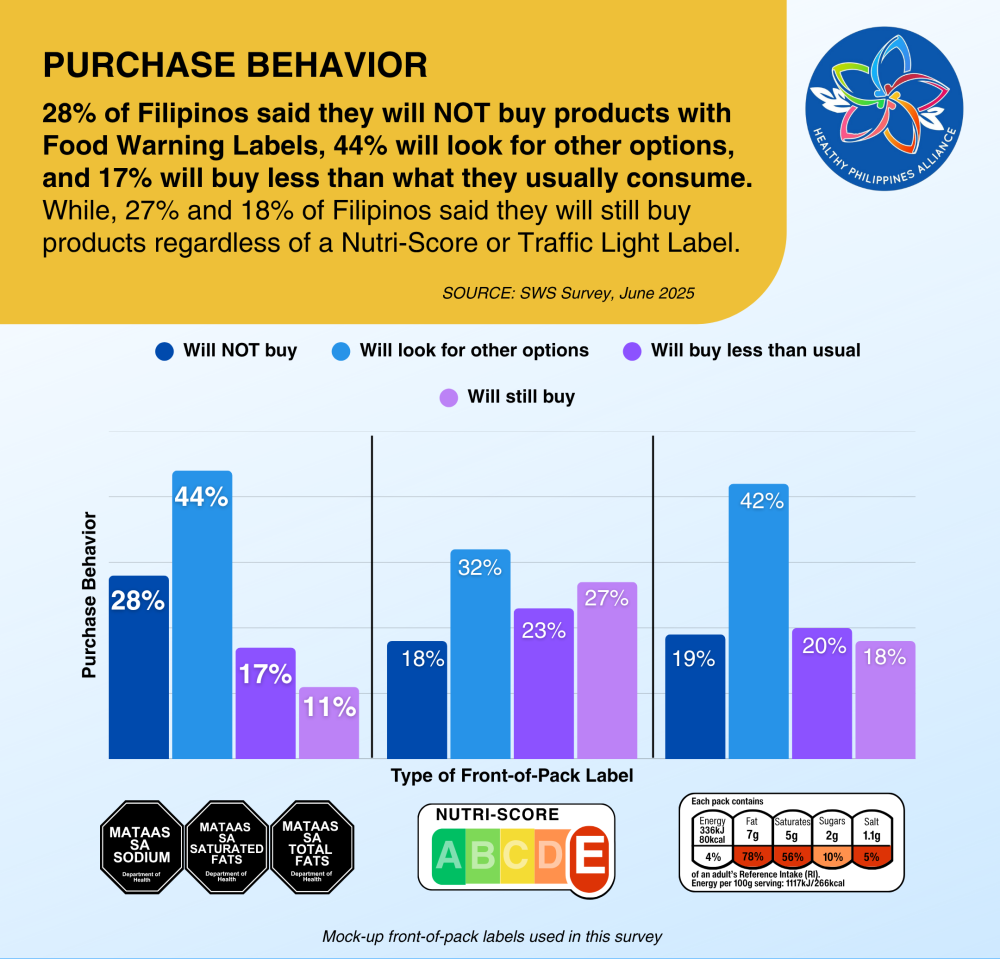

The black octagonal food warning labels delivered better results compared to the Nutri-Score and Traffic Light Label in terms of consumer recall, health perception, and purchase behavior, especially among the 18 to 34 age group. (See infographics on this page.)

According to another survey, conducted by the Social Weather Stations in June, black octagonal food warning labels were also the most striking, with 37 percent of the respondents who examined mock-up food products with FOPL remembering them the most.

Meanwhile, only 16 percent of respondents remembered the Traffic Light Label, while 11 percent recalled seeing the Nutri-Score Label.

“The message is clear: Warning labels on food products are effective,” said Alyannah Lagasca, lead convener of the HPA Youth Network.

“Simple, visible labels guide consumers—including children and youth—toward healthier choices without confusion,” she added.

Industry interference

Health advocates and other nonprofits, including the HPA, warned that the development of an effective and stringent FOPL policy should be protected from interference by food industry representatives.

Rhia Muhi, senior advocacy adviser of Global Health Advocacy Incubator, said food industry representatives may delay the implementation of FOPL systems by pushing for more evidence or research, or by funding studies that present skewed results in favor of their industry.

“The industry has influenced legal and political requirements globally to weaken or impede policies for healthy nutrition development. They delay, distract, and deny,” she said.

“The industry also influences science and academia to shape public opinion in its favor, as well as to undermine state responsibilities favoring private interests,” she added.

Absent an FOPL policy in place, Abanilla warned that the Philippines has an environment that continues to promote unhealthy food products.

“FOPL is truly a preventive tool. It helps consumers make informed choices so they can know which products are healthy and which are not. It will be especially helpful for low-income and low-literacy populations. Without it, we will have greater disparity in our health situation,” he said.

“Non-enforcement of FOPL can contribute to a further increase in the prevalence of noncommunicable diseases, especially in young Filipinos,” he added.