Himself an artist: Pablo Tariman and his life’s work

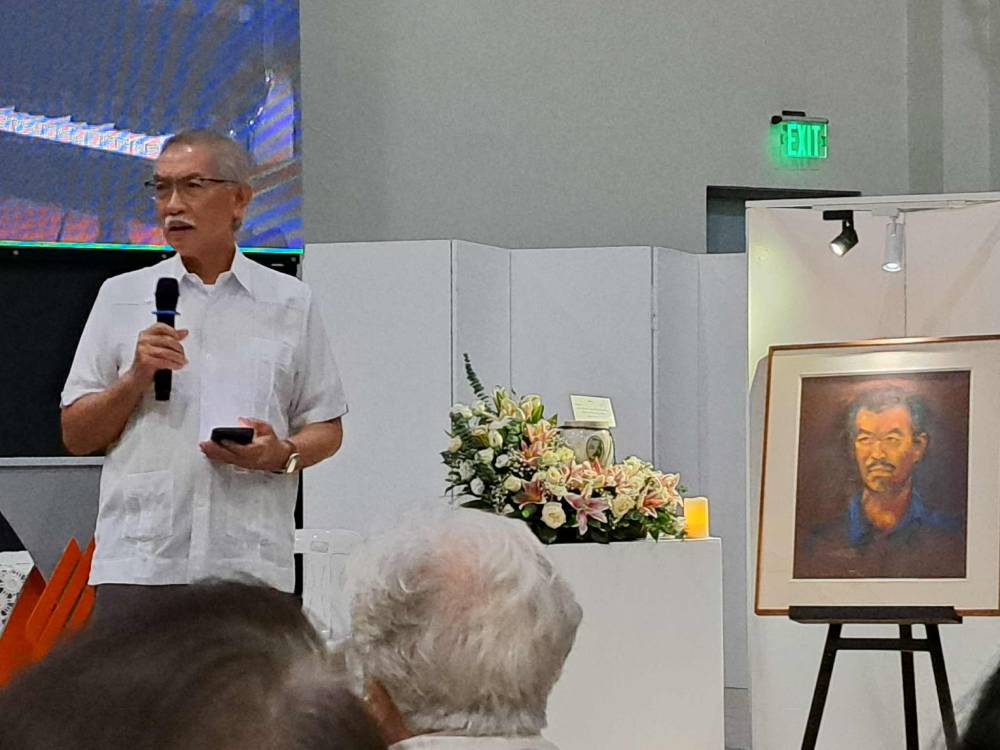

The diversity of those who paid him tribute showed Pablo Tariman’s broad reach in the varied world of the arts and the lives he touched in each genre.

From academics to poets to musicians and activists, friends and family gathered on Oct. 14 at Parola Hall, University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman, to honor the late journalist, impresario, and tireless chronicler of the arts who died five days earlier at the age of 76.

Fr. Robert Reyes led a Mass at the gathering called “In the Key of Memory: A Thanksgiving for the Life of Pablo A. Tariman.” Then tributes to Tariman were made by fellow travelers in the world of the arts, each introduced by actor Joel Saracho, the host of this occasion.

Sociologist, author, and Inquirer columnist Randy David remembered meeting Tariman for the first time at an “after-concert dinner” hosted by film and TV director Marilou Diaz-Abaya, some three months after the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution, when David hosted “Public Forum” which Diaz-Abaya directed.

At that time, that program and other talk shows had a big following among the public, then politicized by the Edsa uprising. David recalled Tariman telling him that “perhaps what we were trying to do for television—which was to bring national issues right to the people’s doorsteps so they could take part in the national discourse—was what he and Cecile [Licad] were doing for music.”

‘Far-flung communities’

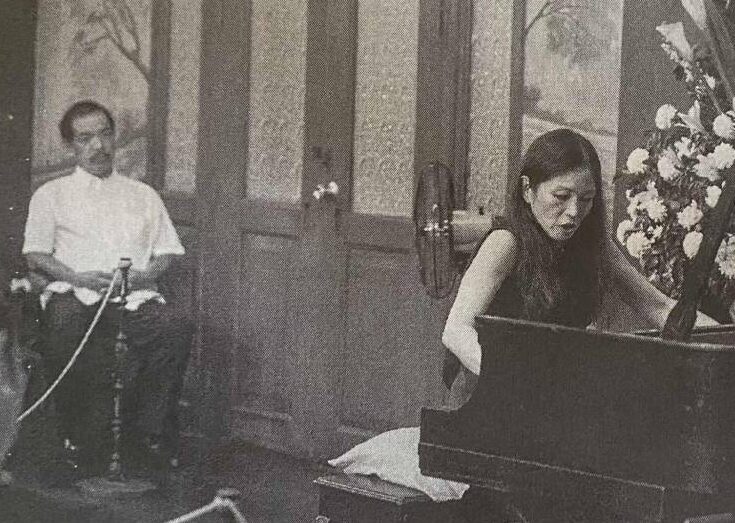

Perhaps no other artist was more associated with Tariman’s lifelong mission to promote Filipino artistry, especially in classical music, than the renowned pianist Cecile Licad.

“He spoke of the concerts they were organizing in far-flung communities to bring Cecile’s music to ordinary Filipinos,” David said. “He described how she relished playing before audiences who came in their simple clothes purely to listen, not to be seen. There were always logistical challenges, he said, finding the best piano in the area, transporting it to an old church or a dilapidated school building. The instrument and the acoustics were rarely ideal, but none of that mattered. What mattered was the encounter, the meeting between artist and audience through music.”

According to his collection of reportage “Encounters in the Arts,” published early this year, Tariman was covering a lot of ground, as usual, in the last three years of his life—from Baguio City to Nueva Ecija to Iloilo City to his home province of Catanduanes.

A concert there by Licad scheduled on Oct. 11 was “first envisioned” by Tariman himself, according to the provincial government. But he died two days before that event.

In Licad’s video message screened at the thanksgiving, she was still wishing Tariman an early recovery while playing snippets of classical pieces on the piano, like Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata.”

“I cannot think of anyone who worked more passionately than Pablo for the democratization of access to the arts,” David said. “[And] because he wrote so much about other artists, Pablo may not have realized that he was himself an artist par excellence.”

‘Persona’

For retired arts studies professor Edru Abraham, Tariman’s articles “about some of the finest Filipino artists were written not only in terms of their art but also their persona.”

Licad, her well-established virtuosity, her human side, even her “kikay” side and her pop sensibilities, were all brought out by Tariman’s writings through the years.

Although Tariman focused mainly on Filipino artists associated with western musical styles, “he was also very encouraging to those that were not necessarily in his metier as a writer,” said Abraham, founder of pioneering ethnic music and dance ensemble UP Kontra-GaPi. “And that is where I come in, because in many instances, Pablo … would come to me since they wanted something different from the western fare in terms of performance. So I owe him that.”

Show biz writer

At the height of his prolific career writing about the arts, Tariman also covered the world of pop culture, especially show business. On two occasions this writer, then an editor for a newsmagazine and later an online site, needed a writer who more or less had the scoop on the entertainment industry.

The first time Tariman helped out was when he covered the Metro Manila Film Festival scandal of 1994, delivering incisive reportage with some juicy tidbits. Much later I needed his help again, but since he had been out of touch from show biz he begged off, only to text a week later saying half in jest, “I’m here at this presscon just for you.” He had easily slipped back in circulation as if he never left that scene.

During the publicity campaign for the 1991 staging of Verdi’s “La Traviata” at the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP)—a high-profile production with its Filipino libretto by poet and dramatist Rolando Tinio—Tariman wrote some gossip trivia intended to promote that opera which he knew would be accepted by the tabloids more than the lifestyle editors.

But no one chided him for crossing over into show biz or giving arts coverage a celebrity spin—unlike three decades earlier when his idol Nick Joaquin raised eyebrows for writing about the “bakya” culture, as the “masa” (masses) were referred to then.

“Pablo is from the province, so he knows the masa mentality,” Abraham said. “What [he was] actually doing is broadening or widening the audience. And while doing that, also educating and raising the consciousness of our ‘kababayan’ (compatriots), and vice versa too. When you do that, the artists who are said to represent the upper classes will better understand the masa if they perform for the masa. It’s not just performance—it’s communication. We forgot that all of these are means of communication.”

Actor-screenwriter Bibeth Orteza recalled a time when Licad sought Nora Aunor as she prepared for a performance at Orteza’s home.

“Cecile, who, it turned out, was such a huge fan of Nora Aunor [as well as] Tirso Cruz III, requested Pablo if they could be invited. So Nora Aunor, Tirso Cruz, and Susan Roces were there,” recalled Orteza. “Pablo was so glad because Cecile enjoyed the night.”

‘Young people’

There have been other changes in the classical scene, as Tariman himself had pointed out on social media before he died.

“I do believe that young people are really getting into the classical arts in general, not just opera,” said Camille Lopez-Molina, one of three sopranos (the others were Stefanie Quintin-Avila and Myramae Meneses) who performed at the gathering.

“Young people have a platform, and I think because of the visibility on social media, they’re not afraid to go into different things,” Molina said. “My group has been going around with ‘La Boheme,’ and it’s mostly young people, really. And in Bacolod, we had an audience of 4,000 people, and we were like—wow, people would come.”

Meneses remembered meeting Tariman “when I was still starting—I was 17, 18 or 19. And it was always very special when he was there, not only because he would write about it, but because I knew he was there to support, to protect, and to listen, so that was always an encouragement.”

“I’ve known him since I was in UP, studying at the School of Music,” Molina said. “I think his biggest contribution … was that he was also reviewing up-and-coming singers and artists. People who were not known, who were just starting—he would invite them to sing for events or write about where they sang.”

Activist daughter

Tariman’s friends who joined the tribute gathering came from varied backgrounds, including poets Babeth Lolarga (editor of “Encounters”) and Marra Lanot and her family (she and Licad are first cousins), activists Satur Ocampo and Renato Reyes Jr. of Bayan, and former Inquirer editors Rosario Garcellano, Pergentino Bandayrel Jr., and Juan Sarmiento Jr.

For Reyes, Tariman should be commended for “the way he sought to bring artists, classical musicians especially, to the provinces. It was always such a joy that he would chronicle how these artists were able to connect with people outside Metro Manila.”

“But on a personal note, Pablo was the father of Kerima Tariman, a dear colleague of ours, and father-in-law of Erickson Acosta. So I think he nurtured revolutionary artists as well,” Reyes said.

David, in his remarks, cited a short essay by Tariman “about his daughter Kerima, who was killed by the military [in 2021, while] doing organizing work in the countryside.”

“The power of that piece lay as much in its poignant words as in what it left unspoken. It was an essay of love and grief distilled to its purest form,” David said.

Tariman, shaking in tears as the Inquirer then reported, claimed his daughter’s body at a funeral parlor in Negros Occidental four days after she was killed. Her husband Acosta was killed the next year by pursuing government troops.

Tariman’s widow, Merlita, the last to speak, expressed gratitude to the “beautiful tribute you all gave tonight” and said she realized that “death isn’t only for mourning but also a cause for celebration.”

She recited a poem by her husband titled “Remains of My Day,” which she described as a reflection of his “true humanity.”