His love for the sea gets deeper thru science

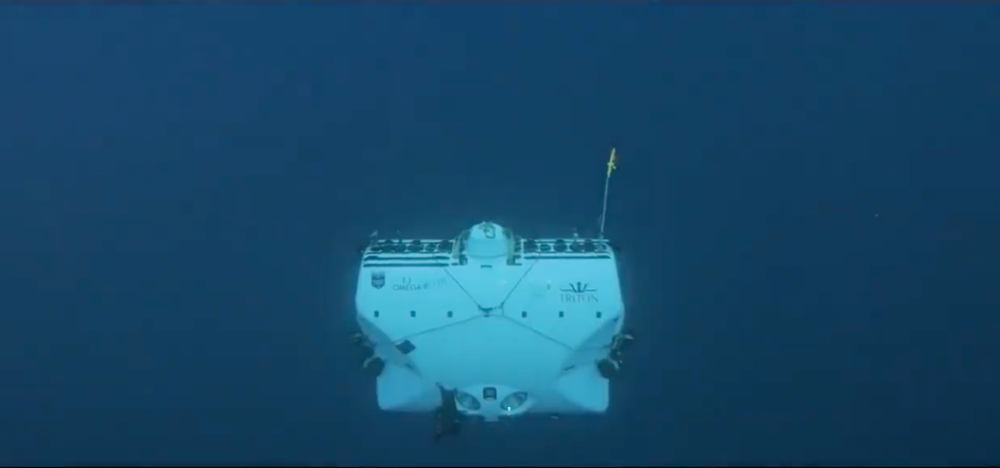

It was no ordinary March morning in 2021 for Dr. Deo Florence Onda as he began to explore another world from inside a titanium submersible, free-falling toward the deepest part of the Philippine Trench.

Outside the small viewport of the DSV Limiting Factor was a darkness few human eyes had ever seen. Yet Onda felt wonder—not fear—like a child opening an encyclopedia, the pictures coming alive.

The descent took nearly five hours, and the ascent, another four. In between, Onda and American explorer Victor Vescovo—whose company Caladan Oceanic made the expedition possible—spent about six hours on the ocean floor of the Emden Deep. It is the third deepest point on Earth, according to the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans, an international database on the world’s oceans.

For Onda, a marine scientist and oceanographer, the dive was not about setting records. It was about seeing, with his own eyes, what he had spent years teaching from textbooks and sensor screens.

“I was awake the entire time,” he said. “It felt like a fairy tale coming to life.”

Recognition

Onda, 38, is among the 2025 The Outstanding Young Men (TOYM) awardees honored this year—cited for his efforts in the field of Marine Science and Sustainability.

He was nominated by Junior Chamber International (JCI)-Puerto Princesa, his home chapter in the global organization promoting leadership among the world’s youth.

“The nomination itself was already enough,” Onda said. “To be recognized by people from your hometown—that meant everything.”

Known as “The Deep Sea Explorer” or “Ang Doktor ng Dagat,” Onda was recognized for using science to help protect Philippine waters—leading pioneering research on marine plastic pollution and building marine laboratories across the country.

According to the TOYM citation, his advocacy and education efforts have served to inspire a new generation of Filipinos to care for the nation’s seas.

Onda’s sense of curiosity can be traced back to his hometown of Brooke’s Point, Palawan, where he grew up just a few hundred meters from the sea.

Unlike the postcard-white beaches that Palawan is famous for, Brooke’s Point has dark sand and lush forests, an agricultural town often called the “coconut capital” of the province.

As a child, Onda spent afternoons collecting starfish and seaweeds, leafing through encyclopedias, lingering over photographs of oceans he could not yet name.

His parents gave him the space to be curious. His mother, who graduated as a chemical engineer and later worked as a civil servant with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and the provincial government, valued education and public service

His father worked closely with indigenous communities, helping develop livelihoods from forest products. This exposed Onda early on to conservation and community work.

“I was never told what I should become,” he said. “I was allowed to explore.”

Visit home

That freedom almost led him to a different path. In the early 2000s, when nursing and medicine promised stability, Onda enrolled in a premedicine program at the University of the Philippines (UP).

But a class in ecology changed everything. It introduced him to the idea that humans and nature exist in a web of interactions. He eventually took up marine science and earned a bachelor’s degree at UP Diliman.

His academic journey later took him to Canada for a Ph.D. in microbial oceanography. He lived abroad for about five years, building a career that could have easily continued overseas.

In 2017, Onda returned to Palawan, but with no intention of staying. He saw himself taking postdoctoral studies in Germany and continuing on an academic path abroad.

That brief visit home, however, changed those plans: Neighbors put up banners welcoming him back. Locals greeted him on the street, eager to know what exactly he was doing. For even in his coastal town here fishing and farming shaped daily life, the idea of a native studying the sea that seriously was unheard of.

One conversation particularly struck him. A child asked him about the ocean—why it was blue, what lived beneath it, how could something so vast be explored. The questioning went on for hours—simple honest, but one Onda couldn’t forget.

“If there’s one child I can inspire,” he thought then, “that’s reason enough to stay.”

Tangible resources

Onda decided to forgo a longer postdoctoral stint in Europe and stayed home for good, joining the faculty of the UP Marine Science Institute in 2018. He went on to become one of only about 30 oceanographers in a country of more than 7,600 islands.

“You ask yourself, ‘Where will I be able to contribute more? Where will I be able to contribute better, and who will actually benefit from my contribution?’” he said.

In 2019, Onda led the “Protect the West Philippine Sea” expedition—a two-week mission involving 74 Filipino scientists and crew. The team studied coral reefs, plastic pollution, and “ocean processes” (as this marine data gathering is called) in the Kalayaan Group of Islands.

By focusing on environmental degradation and food security rather than geopolitics, the expedition made the challenges facing the country’s waters, including the West Philippine Sea, more tangible to the public. It highlighted how science could strengthen the country’s presence in its own seas.

For Onda, this understanding of the country’s resources further crystalized with the Emden Deep dive two years later on the eastern side of the archipelago.

Young audience

During the descent, Onda spotted something painfully familiar: a plastic bag resting some 10 kilometers below the surface.

For a scientist who studies marine plastic pollution, it was a reminder that even the most remote locations are not spared human abuse. The image made the garbage problem more intimate and disturbing.

Thanks to supporters, Onda’s decision to stay in the Philippines because of an encounter with a child has been retold to a wider audience.

Writer and literature scholar Dr. Rose Torres-Yu turned Onda’s story into a children’s book. Published in December 2022, “Ang Doktor ng Dagat” introduced Onda to a younger audience, giving him a moniker that made him more accessible whenever he is invited to speak in classrooms or community gatherings.

Onda never set out to become some heroic, adventurous figure, yet feedback from families began to reach him, with the children saying they now wanted to study science because of him.

“More than the kids,” he said, “you have to inspire the parents. Dreams don’t survive without their support.”

Today, Onda balances teaching, research and community work, mentoring students as they pursue their own marine projects.

******

Get real-time news updates: inqnews.net/inqviber