How Marcos’ ‘return’ helped birth PDI’s Northern Luzon Bureau

In late August 1993, with monsoon clouds settling over Baguio’s ridges, a phone call changed the course of regional journalism in northern Luzon. The assignment was simple, but the timeline was absurd.

Veteran journalist Rolando Fernandez, then semi-retired at 42 after working as reporter and editor for the country’s major broadsheets for more than 20 years and was teaching journalism at the University of the Philippines College Baguio (now UP Baguio), received that long distance call from then Philippine Daily Inquirer provincial section editor Ralph Chee Kee.

“Tapos na ang bakasyon mo (Vacation’s over)!” Chee Kee blurted out.

His instruction: Find an office. Set up a bureau. Do it before Sept. 1.

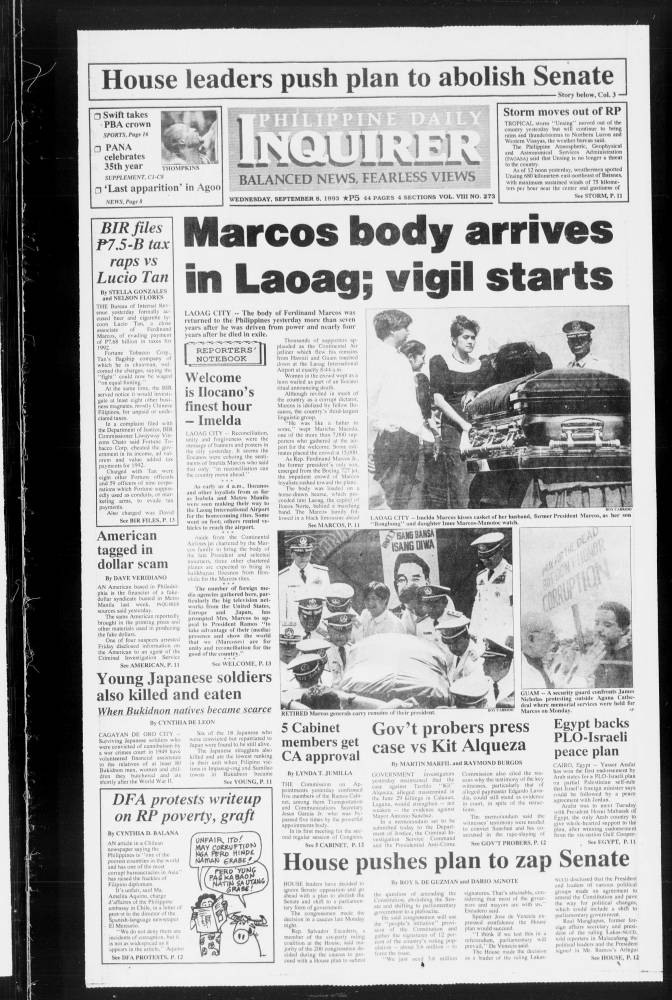

Behind the rush was a historic event: the anticipated return of Ferdinand Marcos Sr.’s remains from Hawaii, where the deposed strongman died in September 1989, to his home province of Ilocos Norte. The Inquirer needed “eyes and ears” in the north, and fast, Chee Kee told Fernandez.

Baguio, where Fernandez and his family had been based for over a year after relocating from Metro Manila, is a strategic center of northern Luzon, including the Cordilleras.

There was no fanfare, no formal announcement for this major editorial arrangement. It was just a quiet instruction and the near-impossible deadline attached to it.

Fernandez, “Sir Rolly” to many reporters whom he had mentored and to hundreds of his students, agreed and immediately went around Baguio looking for any corner that could pass for a modest newsroom. He preferred a space in the city’s downtown, on Session Road or nearby, but the search for that “perfect” bureau office turned out to be difficult. Time was running out.

His friend and fraternity brother, Baguio old-timer and businessman Des Bautista, came to his rescue and offered a space—two studios, one of which could be transformed into an office, in the quiet Happy Glen Loop neighborhood, a five-minute walk from the Baguio Cathedral and Session Road.

The space wasn’t glamorous, but it was enough to start the operations of the Northern Luzon Bureau, the third regional newsroom of the Inquirer after the Visayas Bureau (Cebu City, established in 1991) and the Mindanao Bureau (set up also in 1993 in Davao City).

Fernandez bought a handful of monobloc chairs, a few tables and a basic desktop computer. A fax machine, a key office equipment for newsrooms at that time, followed.

There were still no correspondents or any other bureau staff, but Fernandez was determined to complete the “mission” from Che Kee and the Inquirer newsroom.

First fax

On Sept. 1, 1993—less than a week after Fernandez’s frantic search began—he sent a fax to veteran journalist Carolyn Arguillas, then chief of the Mindanao Bureau in Davao: “We are in business. We are starting operations today.”

That call from Chee Kee, a man of few words but who had clear expectations, gave birth to the Inquirer Northern Luzon. Chee Kee was opinion editor at The Manila Times when Fernandez was the broadsheet’s managing editor. In 1993, Chee Kee watched over the fledgling bureau as it took its first steps.

The coverage of Marcos’ preserved remains’ return was the Inquirer Northern Luzon Bureau’s “baptism of fire.” The bureau had barely been formed and correspondents were still being recruited.

Then correspondents Frank Cimatu, who was based in Baguio, and Teddy Molina, who was based in Ilocos Sur, couldn’t cover the return of Marcos body alone. So the Inquirer and the bureau had to “import” Margot Baterina — the Inquirer’s veteran foreign news editor and a member of a political family in Ilocos Sur who knew the local terrain. She flew in to help steer the coverage that would put the new bureau on the map.

Against all odds, the team pulled off a respectable, even impressive, coverage of Marcos body’s arrival on Sept. 7 that year and the long vigil around the preserved body of the “favorite son of Ilocos Norte” in the Marcoses’ stronghold of Batac. The bureau had been operating for a week, but it already had a national story under its belt.

Professor by day

At the time, Fernandez was also teaching at UP Baguio, continuing his life in the academe mentoring students in UP Diliman while overseeing news operations. He split his days between students and the bureau, pushing through with the stubborn stamina of someone determined not to waste an opportunity.

Money was tight as a UP professor’s salary then was modest. But he had two young children and a wife, a freelancer, a reason to stay in Baguio. The bureau gave him a way to continue his passion for journalism — honed in newsrooms of Manila Evening News, Philippines Herald, Philippines Daily Express, The Manila Times, Manila Chronicle and Daily Globe — without leaving the mountains he had come to love.

Slowly and deliberately, he began building his team. Early on, Fernandez sought guidance from then Inquirer editor in chief Letty Jimenez-Magsanoc, asking her the principles that the Inquirer’s youngest bureau should live by. Her answer was characteristically brief — and uncompromising: “Live by our motto: Balanced news, fearless views.”

So with that marching order in mind, Fernandez went across provinces in northern Luzon interviewing potential correspondents—some seasoned, some completely raw. He relied on instincts rather than resumes.

Robert Jaworski Abaño, Fernandez’s former student at UP Diliman, joined the bureau four years later as deputy and chief of correspondents, helping steer its day-to-day operations. Working closely with Dormie Villamil, the bureau’s first editorial assistant, and later Gobleth Moulic, also a former student who would later take Villamil’s place after the latter resigned, he became part of the core team that kept the young newsroom running with rhythm and reliability.

Abaño would later rise through the ranks, eventually becoming one of the Inquirer’s editors at the main newsroom in Makati City. He now serves as the paper’s managing editor.

Manpower

Over the years, Fernandez filled most provinces in the Ilocos, Cagayan Valley, Central Luzon and the Cordillera regions. Among the earliest community journalists to have worked with the bureau was the late Anselmo Roque, a Palanca award winner and a pioneer provincial correspondent of the Inquirer.

Fernandez tapped reporters from local newspapers and radio stations, those working for the Philippine Information Agency, staff writers and researchers of nongovernmental organizations, teachers from local universities and colleges, local artists and photographers, and even former correspondents of other broadsheets to strengthen the bureau’s manpower.

Fernandez also drew talent from his own classroom. Some students he trained in UP Baguio later became bureau mainstays—and editors in their own right.

Many of the bureau’s recruits in the 1990s through the early 2000s, like Nathan Alcantara, Vic Alhambra, Russell Arador, Leoncio Balbin Jr., Richard Balonglong, Bert Basa, Cristina Arzadon, Vincent Cabreza, Estanislao Caldez (+), Desiree Caluza, Gabriel Cardinoza, Delmar Carino, Cimatu, Jo Clemente, Gia Damaso Dumo, Alfred Dizon, Ben Moses Ebreo, EV Espiritu, Armand Galang, Melvin Gascon, Eric Jimenez, Ansbert Joaquin, Peter La. Julian (+), Willie Lomibao, Jun Malig, Ashley Manabat, Tonette Orejas, Artha Kira Paredes, Juliet Pascual, Greg Refraccion, Carmela Reyes-Estrope, Joya Santos-Doctor, Toots Soberano (+), Yolanda Sotelo, Benjie Villa (+), Cesar Villa, Villamor Visaya Jr., Ray Zambrano and Andy Zapata would stay with the Inquirer for years.

They covered everything: local government and politics, elections, peace and order, the military and insurgency, traffic accidents, volcanic eruptions, typhoons, political dynasties, land disputes, the environment, mining, indigenous peoples and tribal conflicts, even business, sports, lifestyle and the long list of “running issues” that shaped the north.

Bureau meetings set in Baguio and in different provinces in northern and Central Luzon were occasions to assess performance and set the coverage direction. Learning sessions with Inquirer editors from the central newsroom in Makati were included in these meetings.

Fernandez instilled in correspondents and bureau staff the practice of accuracy and fairness in reporting and the respect for facts, the basic tenets of journalism. He recalled an incident in 1998 when a correspondent fell for “fake news,” when this phrase had yet to become “popular,” reporting about remarks supposedly made by then President Fidel V. Ramos when asked about the prospects of having his giant bust, similar to Marcos’ concrete bust, built in Tuba, Benguet. The story collapsed almost immediately: Ramos had never visited Tuba at the time, and that comment attributed to the chief executive was nothing more than hearsay.

To show he was serious about credibility and accuracy, Fernandez suspended the correspondent.

Legacy rooted in people

Looking back, Fernandez, now 75 and who retired from the Inquirer in 2021, knows the bureau’s contribution wasn’t just measured in scoops or headlines. It was in training regional reporters. It was in giving readers from the so-called “Imperial Manila” and other provinces a window into the north. It was in bringing local color, context, and first-hand knowledge into national stories that would have otherwise been flattened into statistics.

What began as a humble, bare studio eventually became one of the Inquirer’s strongest regional arms, which was steered by veteran journalist Ma. Edralyn Benedicto after Fernandez’s retirement. Benedicto, now the Regions editor, served the Inquirer for more than 30 years in various capacities as chief of the Visayas, Southern Luzon and Mindanao bureaus. She also served as editor of Cebu Daily News, the Inquirer’s sister publication.

Ask Fernandez today what he’s proudest of, and he won’t mention the bureau’s early scoops or its survival through the COVID-19 pandemic and its continued operations under the Marcos administration, this time through the son, President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., a former Ilocos Norte governor, representative and senator before being thrust into national politics as senator.

Fernandez will talk about people—the Inquirer correspondents who stayed, the students who became part of the bureau and carved a career in the media, and the communities whose stories were told. And especially the editors — like Chee Kee and his successor as Across the Nation editor Jun Bandayrel — who guided the bureau quietly from afar.