Ifugao lawyer backs fellow IPs with legal aid, education

Raymond Marvic Baguilat recalled one evening in 2021 when he froze at the sight of a man who appeared to be a police officer driving his motorcycle alongside Baguilat’s vehicle.

The activist lawyer suddenly had a bad feeling this could be an attempt on his life. President Rodrigo Duterte was in his penultimate year in power, but his government with its track record of “Red-tagging” still posed a threat to human rights defenders. Baguilat at that time was Red-tagged as a supporter of communist rebels.

But that moment passed without incident. Still, it served as a reminder of the risks he faced in defending the indigenous peoples (IPs).

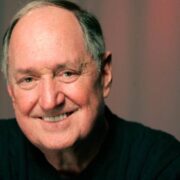

Baguilat, 39, is himself a member of the Tuwali people in Ifugao province. For his work in helping promote IP rights through education, law and justice, he was honored this year by Junior Chambers International (JCI)-Philippines as one of The Outstanding Young Men (TOYM) of 2025.

His already extensive experience includes private practice as well as serving as chief legal officer of the Institute of Human Rights of the University of the Philippines’ (UP) Law Center and program head of its Indigenous Peoples Law and Policy Program.

He was also one of those who drafted the Tourism Code of his hometown Kiangan and the Intellectual Property Protection Ordinance in the town of Hungduan.

Prejudice, insults

Since his work covers IPs across the country, Baguilat also helped draft the implementing rules and regulations on the Bangsamoro Indigenous Peoples Act of 2024 and the joint administrative order of the Commission on Human Rights on overlapping land claims.

Baguilat believes he was led to his current advocacy since childhood, experiencing the prejudice, insults and discrimination confronting the IPs.

“This is not just personal,” he said in an interview with the Inquirer. “If you are told you’re from the mountains, the idea is that you are either… backward or slightly ignorant. At that time [when I was young], I couldn’t really understand.”

As a child, he would often be asked if he was hiding a tail, or if he was a savage, headhunter, or drug user.

This experience prompted him instead to turn to Ifugao values such as “baddang,” or the tradition of mutual aid and collective strength.

“I saw that I just needed to unpack what happened in the past and… go around the province and speak with different indigenous peoples,” he said.

Starting in 2010, before graduating from the UP College of Law, he worked as a consultant for then Ifugao Rep. Teddy Baguilat, his cousin. He was also involved in the House committee on indigenous peoples, headed at that time by the lawmaker.

Legal education

The younger Baguilat said he became “more exposed” to the different IP groups, from the Ayangan and Kalanguya in Luzon to the tribes in Mindanao. In Ifugao, he volunteered as adviser to various youth federations. Eventually he worked alongside other IP advocates such as Victoria Tauli-Corpuz of the Kankana-ey Igorot group who was then a special rapporteur of the United Nations.

“We all share the same sentiments that there is injustice against us, there is discrimination. And then, you would suddenly think, why do these things keep happening? You keep hearing it, but nothing is really happening to solve it,” he said.

Apart from his almost 14 years as a lawyer, Baguilat has also been involved in legal education. At the UP College of Law, he led the revival in 2022 of a course on laws regarding IPs after it had been shelved for over a decade.

Since then, 178 students have enrolled in that course called Law 132 or Philippine Indigenous Law, while its graduates are now practicing lawyers who “continue to champion indigenous rights,” he said.

Under the Legal Education Board (LEB), which is attached to the Commission on Higher Education, Baguilat also encouraged IPs aspiring to be lawyers to avail themselves of that agency’s scholarships under its Legal Education Advancement Program. JCI said his efforts in legal education have allowed indigenous voices in the legal discourse.

“That has been my dream, for the IPs to be lawyers and return to their roots,” he said, as he cited one of his law students who now heads the IP Affairs of the Commission on Human Rights.

‘Give people hope’

Baguilat has courted the government’s ire in the course of his work for IPs. Red-tagging, for him, has a chilling effect, since not a few human rights defenders have been killed after being labeled communists.

He also counts himself a victim of fake news, after a website claimed that he and other lawyers of former Sen. Leila de Lima, who was then in detention during the Duterte administration, had been apprehended by airport authorities.

Despite these threats, Baguilat regards his role as a lawyer as one that goes with the responsibility of giving people hope.

“Because if you don’t give them hope or do not have hope at all, why else would they approach someone who is a worker for the law?” he said.

“That’s the most important thing, to make them trust and hope that the rule of law can be a shoulder for them to lean on. Why else would they approach us? That is why I myself have to trust as well that there’s a solution,” Baguilat said.