Igorots of 66th Infantry: Baguio’s wartime heroes

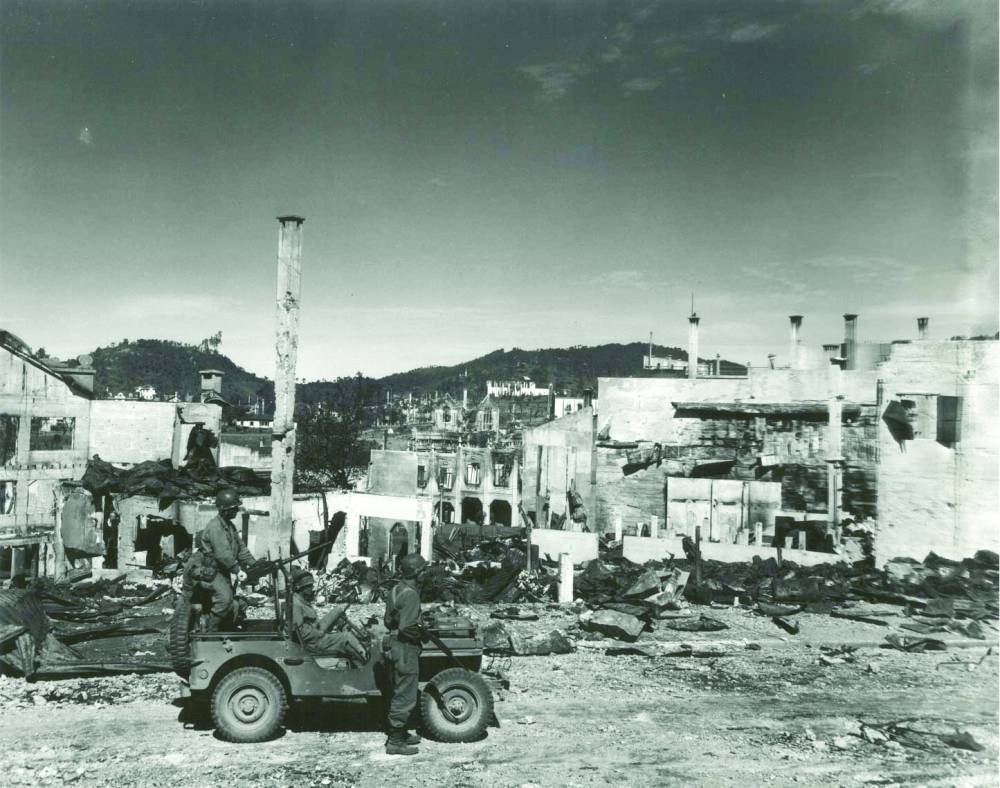

BAGUIO CITY—Eighty years ago, Baguio bore the full brunt of World War II in the weeks leading to the city’s liberation from the Imperial Japanese Army on April 27, 1945.

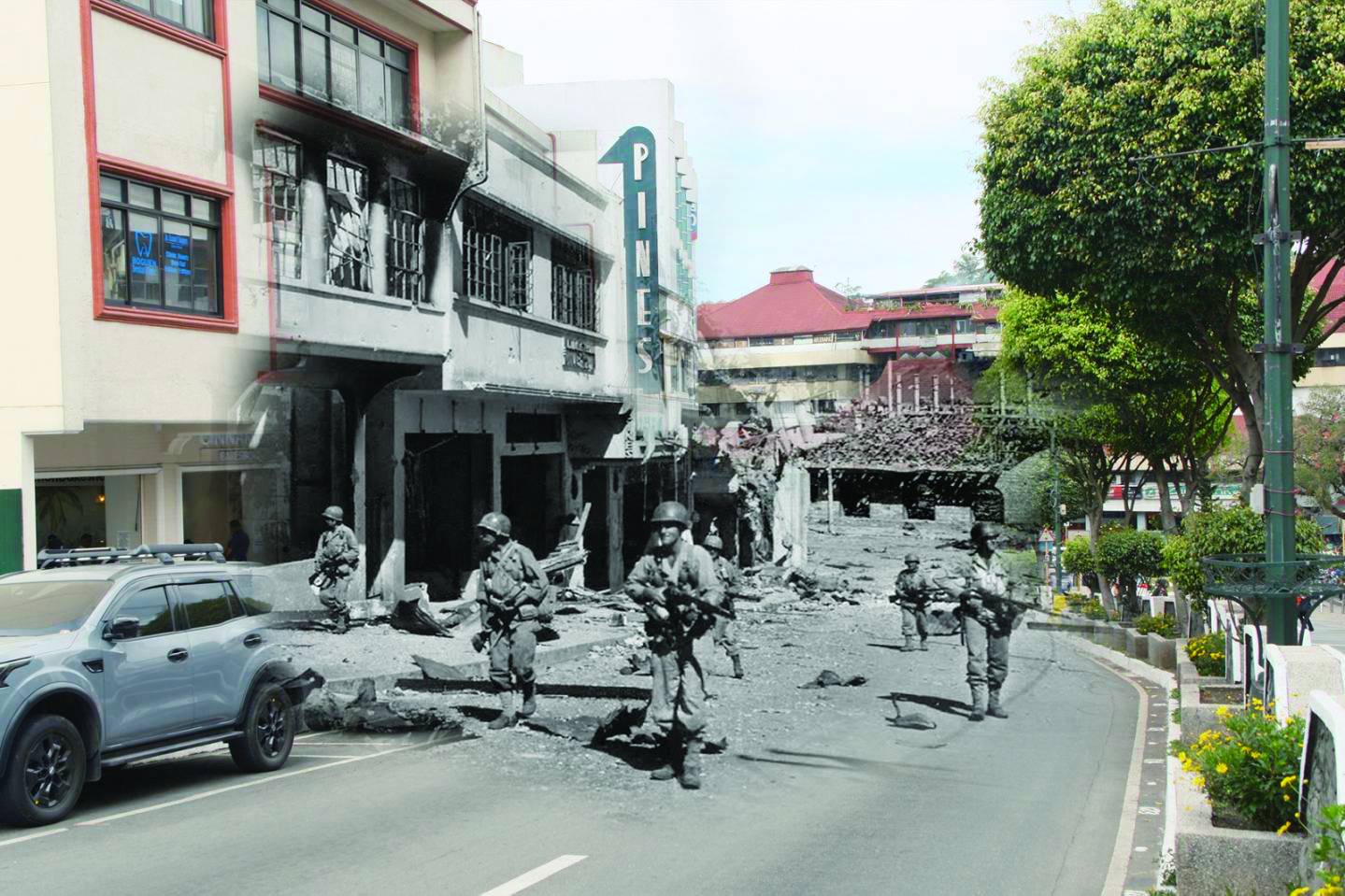

A privately funded memorial exhibit called “80 and Still Free” that opened at SM City Baguio on April 21 features archival photos and digitally modified portraits of devastation during the city’s “Liberation Day.” American bombers had flattened this mountain resort city—leaving only a few buildings intact, like the Baguio Cathedral—as Allied Forces pushed back the retreating Japanese invaders.

Baguio is historically where the Pacific war started and ended in the Philippines, according to the University of the Philippines experts, like history professor Ricardo Jose, in a 2020 lecture. Japanese bombers flew from Taiwan and struck the John Hay Air Station on Dec. 8, 1941, a day after Japan joined the global conflict on the side of Germany’s Adolf Hitler by attacking Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Commonwealth President Manuel Quezon was in Baguio at the time and had witnessed the John Hay bombardment, Jose said.

The city was soon taken over by the Japanese, who installed the northern Luzon branch of the Japanese Military Administration here, in order to control strategic targets like the Benguet mines in Itogon and Mankayan towns for their valuable copper and manganese. Baguio was also the last stronghold of Japanese Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita in the last days of the war.

Yamashita was cornered by the 66th Infantry and American forces in Kiangan, Ifugao, and was returned to Baguio to formally surrender at Camp John Hay on Sept. 1, 1945, completing the tragic circle.

‘Mighty 66th’

The Japanese kept a tight leash on Baguio during its four-year occupation, but was constantly beset by guerrilla operations from the Ibaloys of Baguio and Benguet, who were part of the legendary infantry regiment called the “Mighty 66th.”

This was a reference to the guerrilla unit formed by survivors of the Bataan Death March in 1942, American soldiers and engineers who escaped capture, and the indigenous peoples and other Baguio residents who volunteered to fight for their families.

The descendants of many Ibaloy women who prepared meals or washed the uniforms of Japanese soldiers revealed that they were actually spies, whose information allowed soldiers and civilian volunteers to sabotage the invaders’ operations, or for the much-feared “bolo men” to ambush Japanese patrols.

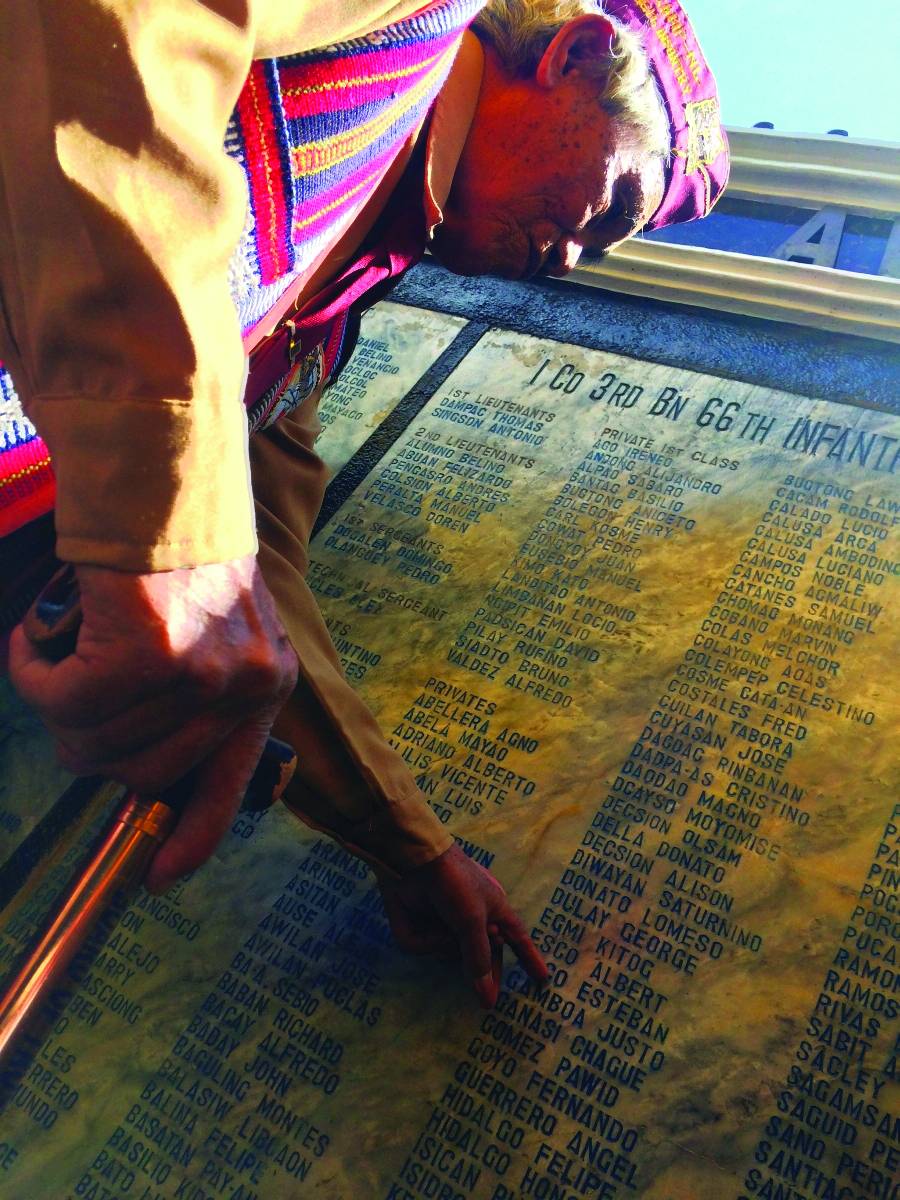

But the most accessible records today focus solely on the American soldiers and the tanks that triumphantly rolled into Baguio, with nary a snapshot of the Igorot soldiers and guerrillas who fought by their side.

Once the war ended, many of the Ibaloys who fought the Japanese returned to their lives before the war, as farmers or teachers, “and rarely spoke about their bloody experiences,” said Julie Fianza, daughter of the late Daniel Fianza, who joined the guerrilla campaign alongside brothers Ismael, Emmanuel and Samuel. This explained the scant records about the Igorots in the years following the war, she said.

This silence was also common to veteran soldiers like the late Gen. Pedro Baban, who served as one of the three captains of the 66th Infantry, according to his grandson Gabriel Baban Keith. A member of the Philippine Military Academy Class of 1940, Baban was deployed to fight the invasion along with senior cadets of Classes 1942 and 1943 who were prematurely commissioned as officers because of the war. “But he resisted telling us his war experiences,” Keith said.

On moments when Baban opened up, Keith said his grandfather often declared that “war is hell.” He said Baban once confided in him about the sheer terror he felt in “each encounter with the enemy,” only for numbness and military skills to reign. “The enemy bullets just whizzed past his ears when he fought,” Keith recalled, quoting Baban.

Documentation

In recent years, stories about the Cordillera war fighters have become prominent, driven by documents and recorded video and audio accounts shared by these liberators that their Ibaloy children and grandchildren have been collating.

Only a few war veterans are still alive to testify about how war changed so many lives, such as 98-year-old Ernesto Luis, who participated in Baguio’s first joint memorial service for Filipino and Japanese soldiers and their descendants on April 20.

The number 66 was actually the “sum” of 43, 11 and 12—the 43rd Infantry of the Philippine Scouts; and the 11th and 12th infantries of the Philippine Army, whose soldiers made up the unit, said Florimond Milo Esteban, an engineering professor and son of the late Lt. Florencio Esteban.

Florimond read part of his father’s manuscript about the war during this year’s “Araw ng Kagitingan” program on April 9. He said Esteban and other Ibaloys rejoined the resistance in Benguet after escaping the Death March, and were deployed to snatch a radio transmitter in Baguio, as well as conduct a raid on Easter School where the Japanese stored their weapons and ammunition. Both missions failed, Florimond said.

But he said Esteban’s unit succeeded in escorting First Lady Esperanza Osmeña and her three children to safety in February 1945 from Baguio, where she had been staying, to Kapangan town in Benguet. Her family hiked down the Benguet mountains to Pangasinan province. President-in-exile Sergio Osmeña had succeeded Quezon who died in 1944, and was with American Gen. Douglas MacArthur when Allied Forces finally landed in Lingayen in January 1945 to free the Philippines.

Esteban’s manuscript detailed the fierce battles to liberate Baguio along Naguilian Road, Kennon Road and the Mountain Trail (now Halsema Highway), as each step upward was slowed down by Japanese defenses. The invaders destroyed all bridges along Kennon, making the climb more difficult for the Allied Forces. Esteban’s document disclosed one instance when an American tank toppled along what is now Barangay Irisan in Baguio, killing a soldier.

Defiance

The combined forces finally got through on April 27 by accessing Loakan Airport, but “as to who arrived first is debatable,” Esteban wrote.

The 66th Infantry helped recapture Bessang Pass in Ilocos Sur on June 14, 1945 and the mines of Mankayan, Benguet, where Esteban was almost killed by a Japanese sniper. “I noticed my body was sprinkled with blood and human flesh,” he wrote, discovering that his companion, Private Guzman Suerte, took most of the hit from a machine gun.

One of his fondest recollections involved a visit by that period’s popular American comedian, Bob Hope, who performed at what is now Camp Dennis Molintas, named after the major who led the 66th Infantry.

“[Major Molintas] was known to be strict. But during a formation, he saw a soldier who had no uniform. He was told about a shortage of uniforms, so he took off his uniform and gave it to the soldier, Villanueva Patting, in a story related to me by one of [Patting’s] sons,” recalled Baguio Councilor Jose Molintas, Major Molintas’ nephew.

But some of the stories reflect the paranoia and racism that the Igorots, and all Filipinos in general, have had to overcome in the course of driving away the Japanese.

Fianza said stories of atrocities committed by both the Japanese as well as by the guerrillas who executed the “makapili,” or collaborators, “were only shared in whispers among us children.”

Major Molintas often defied American orders to execute suspected traitors, his nephew said. He refused to kill an Ibaloy named Marquez, and had told his American counterparts that if they “continue killing our Ibaloy leaders without [our] clearance, we guerrillas might as well treat the Americans as enemies,” said Councilor Molintas.

Even the 66th Infantry’s Col. Bado Dangwa, who founded the Dangwa Bus Line in 1928, was targeted for execution by the Allied Forces because of suspicion that he “entertained Japanese soldiers to protect his transport business,” Councilor Molintas said. “Felipe Tio-tiw, known as the ‘Tiger of Halsema’ for single-handedly eliminating a squad of Japanese soldiers, told me that the 66th [Infantry] sought the advice of Major Molintas,” he narrated.

“He said war is temporary and once there is a cessation of hostilities, we would need brilliant people and businessmen like Dangwa to develop the area in the old Mountain Provinces. He told them to recruit Dangwa to the guerrilla unit where he was immediately assigned as finance officer,” Councilor Molintas said.

The Philippine National Police’s regional headquarters in the Cordillera has been named Camp Bado Dangwa, after the soldier and entrepreneur.