In a coastal Pangasinan village, ‘bagoong’ isn’t just food—it’s culture

LINGAYEN, PANGASINAN– There’s something special in the air—or perhaps the very environment—of Barangay Pangapisan in this capital town that gives its bagoong (fermented fish paste) its delicate consistency, savory flavor, and distinct aroma, making it a beloved Filipino condiment.

At least, that’s the theory of a long-time bagoong maker after a batch from his factory, which was brought to a southern province for fermentation, failed to develop the same quality as the batch left behind in Pangapisan.

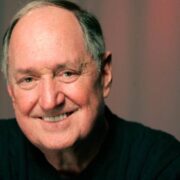

Menardo Molina, 60, the owner of Merly’s Bagoong, recalled a time when visiting students from a state university conducted research on the bagoong industry.

“They brought a jar of freshly mixed fish and salt from a batch we prepared here and followed our instructions carefully. But after six months, they came back and showed us the result, which turned out to be of poor quality,” Molina tells the Inquirer in a recent interview.

While natural factors may contribute to the superior quality of bagoong produced in Pangapisan, Molina believes the industry thrives primarily because of the villagers’ dedication and hard work.

There are around 50 bagoong makers in the town, most of whom operate small, home-based businesses. Despite their modest scale, their products now grace the shelves of high-end supermarkets.

History

Though no official record exists on when bagoong making first began in this coastal village, Molina believes it dates back to his wife’s grandparents, who were already involved in the trade in their youth.

“It probably started with fishermen who had surplus catch from the Lingayen Gulf—fish they couldn’t sell. So they preserved it by turning it into bagoong,” Molina explains.

Molina himself began his career as a vendor, selling bagoong fermented in earthen jars, or tapayan, in his parents-in-law’s backyard. He also bought bagoong in bulk from Bataan and resold it in the wet markets across Pangasinan.

After marrying Merly, he ventured into making alamang (shrimp paste) before expanding to fish bagoong.

“Eventually, traders began trusting us with financial capital, which allowed us to grow the business,” he shares.

Merly’s Bagoong formally opened in 1985 and now employs 20 regular workers, with the number doubling during peak demand. Like many other producers, they now use plastic drums and concrete ponds for fermentation, as the traditional tapayan, which holds only about 20 liters, can no longer accommodate their growing production.

“We’re one of the few who still have tapayan inherited from my wife’s grandparents. That’s why the local government asks us to open our factory to visitors during the Bagoong Festival,” Molina states.

The Bagoong Festival, held every March, honors the town’s iconic product and its dedicated makers. It also features a cooking competition that highlights the culinary creativity of using bagoong as a key ingredient. Bagoong is even designated as Lingayen’s “One Town, One Product.”

In earlier times, villagers used fish caught from the Lingayen Gulf for fermentation. However, that’s no longer the case.

Today, fish—already slightly salted—are delivered in truckloads from Quezon, Marinduque, and the Bicol region. The varieties used include monamon (anchovy), tamban (herring), and terong (bonnetmouth), the latter being preferred for its lower histamine content.

Meanwhile, juvenile shrimp for alamang and juvenile siganid (locally known as padas) are still harvested from the Lingayen Gulf.

The salt used for fermentation, Molina notes, comes from the western Pangasinan towns of Dasol and, more recently, Bolinao—both of which produce premium salt that may also be part of the secret behind the savory taste of Lingayen-made bagoong.

“Iodized salt is never used because it ruins the mixture. We just add a little food coloring to prevent it from turning too black,” he explains.

Meticulous reprocessing

The true magic, however, lies in the meticulous reprocessing of the fish: re-washing, removing impurities, and re-salting before placing the mixture in fermentation ponds or containers.

Then comes the waiting period—six months to a year—until the patis (fish sauce) rises to the surface. The patis is skimmed off, and the remaining mixture is processed into boneless bagoong by grinding and sifting out the solids.

Both patis and bagoong are then bottled and boxed for sale.

Today, Merly’s Bagoong produces thousands of bottles of boneless bagoong, patis, and padas, which are purchased in bulk by traders from various provinces.

Molina remains confident about the future of the industry.

“As long as Filipinos love bagoong with their vegetables and other dishes, we’ll never run out of a market,” he says.

“In fact, there are locals who want to start their own bagoong businesses now. The market is there, but it’s not that easy anymore because the cost of putting up factories, concrete ponds, and other materials has skyrocketed,” he adds.