In search of ‘Ma-yi’ and the roots of PH-China links

In a quiet lakeside community, archaeologists are digging for clues to what may be the first known mention of a community called “Ma-yi” in ancient Chinese text.

Ma-yi, as can be gleaned in Chinese records dating back to 971 CE, was a trading polity or group that formed in precolonial Philippines.

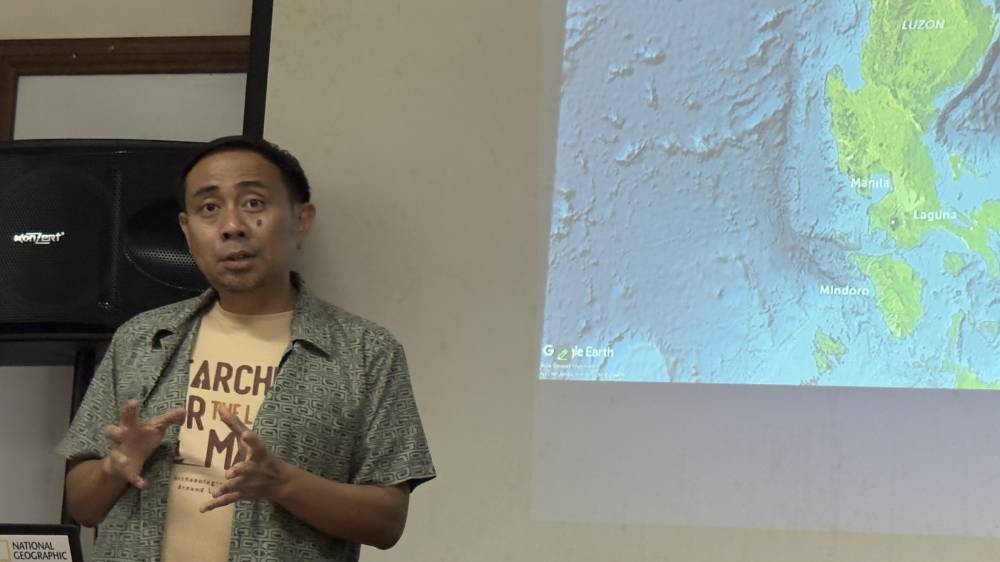

At a lecture hosted by Binalot Talks in the University of the Philippines Diliman on July 9, archaeologist Taj Vitales of the National Museum of the Philippines presented new findings from a recent dig in Lumban, Laguna. The excavation was part of an investigation of the settlements that once thrived along the shores of Laguna Lake.

Ma-yi first appeared in Song dynasty documents as a participant in the luxurious Chinese foreign trade in the 10th century. Later records in the Song and Yuan dynasties give glimpses into life and trading in Ma-yi.

While many scholars have long associated Ma-yi with Mindoro due to phonetic similarities with Mindoro’s supposed old name “Mait,” others like José Rizal, Ferdinand Blumentritt, and Filipino Chinese historian Go Bon Juan have linked it to Luzon Island.

Old site of LCI

Vitales noted that lakes, like rivers or seas, could sustain trading communities. “While we actually try to address these questions of where Ma-yi actually is, I also want to highlight the role of another body of water … and these are the lakes,” he said. “Rivers are the most highlighted water spaces to understand the growth of societies [but] there are actually other civilizations that have grown around lakes.”

Vitales’ team focused on Lumban, where the Laguna Copperplate Inscription (LCI) was discovered in 1989. Written in Old Javanese Kawi script and dated to 900 CE, LCI is the oldest written document found in the Philippines. It told of a debt being condoned and hinted at a stratified, maritime society.

“The LCI, which contained compelling evidence of 10th-century maritime societies here, seems to be the only evidence we have of that period so far. The lack of such evidence was among the first major questions we hoped to address through the investigation,” Vitales said.

Since 2024, the team has opened three excavation trenches along the Lumban River, near the original findspot of the LCI.

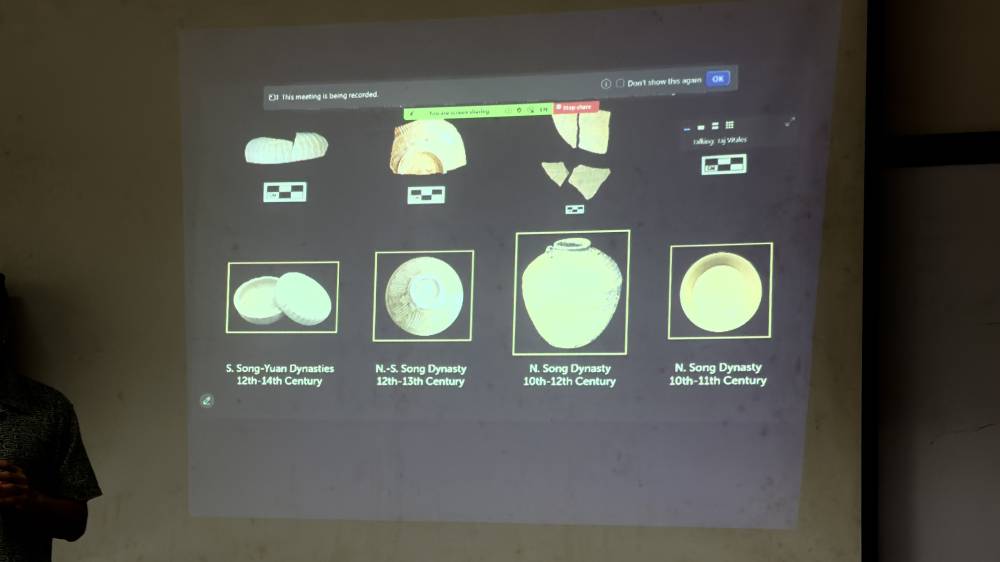

Ceramics were the most commonly unearthed materials in the dig, with most sherds—broken pieces of pottery—dated between the 12th and 15th centuries.

Complex social structure

They also found Chinese clay. In the upper, younger layers, there were sherds dated to the Song and Yuan dynasties, including what appeared to be part of a celadon powder box with linear designs characteristic of those periods.

Certain sherds at the lower level display motifs and features akin to Chinese work, most likely from the 10th to 12th centuries. These include jar fragments with linear wavy motifs similar to those from the “northern,” or earlier period of the Song dynasty, and sherds comparable to beadware in the 11th century.

The findings, Vitales noted, need further examination. But while he could not definitively answer whether their findings in Laguna de Bay are from Ma-yi, he said the complex social structure implied by the findings in Lumban showed similarities to the polity identified in Chinese texts.

“We can see how there is a certain hierarchy of officials and … a wide, complex maritime effort … This in itself is already proof of a very well-developed social context [in the] 10th century,” he said.

The team envisioned a possible local industry of early Lumban communities: metalworking, pottery production, weaving and trade. “It could appear that it’s not actually a single entity. It might be a confederation,” he added.

What surprised the team was evidence of occupation dating back to the first millennium CE, several centuries earlier than thought. Unearthed sherds similar to those found in earlier digs in Pila, Laguna, and Batangas were dated to this time. Also uncovered were Indo-Pacific glass beads of the same period.

Glimpse into diet

Animal remains, including pig teeth, buffalo bones, deer antlers and “kanduli” (marine catfish), provided glimpses into the diet of early inhabitants. Another unexpected find: a sawfish vertebra, suggesting this now-rare species once swam abundantly in Laguna de Bay.

Vitales clarified that at the time, neither the Philippines nor China was a unified country, both only made up of different groups.

“We see each other as partners for [the] exchange of goods. We never talked about military power,” Vitales told the Inquirer. “I think the Chinese recognized the maritime power of some states,” he added.

Chinese ‘recognized us’

For Teresita Ang See, civic leader and trustee of the Kaisa Heritage Center, the mere mention of Ma-yi in ancient Chinese records reflected how it was seen as an advanced society.

“The fact that they put that in an ancient Chinese record [shows] how they recognize [us],” she said in an Inquirer interview. “It’s our point of view that we are much advanced in civilization—that even the [kingdoms] of China recognized us.”

Vitales’ team plans to expand its work to other lakeside sites. Recent surveys in collaboration with Taiwan have identified new potential areas for excavation.

Community participation has played a key role in the project. “With the cooperation of [the] community, it will not only help save their cultural heritage but also the whole lake itself as its natural wonder and testament to the outstanding history of the Laguna de Bay region,” he said.