Kapampangan cuisine: A taste of PH ‘culinary heartland’

ANGELES CITY— Kapampangans went to great lengths to celebrate their cuisine in time for Filipino Food Month this April. Aside from hosting the national launch on April 5, their initiatives went three ways earlier.

On Feb. 26, the Pampanga provincial legislative board passed Ordinance No. 863, which Gov. Dennis Pineda approved on March 7. The local law declared Pampanga the “culinary capital of the Philippines” for so many reasons, including its “long uninterrupted reputation for being home to culinary talents — from the chefs who cooked for the Malolos Congress in Barasoain [Malolos, Bulacan] in 1898 to the chefs who prepared the meals for the athletes of the 30th Southeast Asian Games in 2019.”

Pampanga, the board said, also produced the country’s top cooking experts.

On March 4, former president and now Pampanga Rep. Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, along with fellow Pampanga lawmakers, Senior Deputy Speaker Aurelio Gonzales, Anna York Bondoc and Carmelo Lazatin II, filed House Bill No. 10014, seeking recognition for the province’s “formidable culinary history” and for being a foodie destination by declaring it the “culinary capital of the Philippines.”

The four lawmakers and provincial officials, on March 18, mounted in Congress a food exposition of 73 dishes and desserts to, according to Arroyo, “present the essence of Kapampangan culinary heritage and its potential as part of the greater national culinary identity.”

Last month, the Center for Kapampangan Studies (CKS) of the Holy Angel University held its first International Conference on Kapampangan Cuisine and Food Tourism, gathering culinary heritage advocates, food and family historians, chefs, gourmands and tourism students. The two-day conference on March 21 and 22 featured 11 plenary sessions, 36 parallel talks, 10 cooking demos, an art exhibit, a food bazaar and a bookfair.

Straight away, the CKS expressed its bias for the description “culinary heartland” instead of being the country’s “culinary capital.”

“When we started preparations for this event late in November, I think, we stated in our invitation letters that we conceived this conference to help cement our reputation as the ‘Culinary Capital of the Philippines,’” Robby Tantingco, CKS director, said on the opening day.

‘Epiphany’

“But along the way, we had a paradigm shift — an epiphany, if you will. With the guidance of Madame Felice Prudente Sta. Maria, one of the outspoken and articulate bearers of our country’s culinary history, we looked for an alternative word that reflected our best intentions and our truest aspirations. And we found it. So instead of ‘culinary capital,’ we now use ‘culinary heartland,’” Tantingco said.

Kapampangans did not coin both terms, as he pointed out.

“Culinary capital” was by public acclamation. The global media company Conde Nast praised Pampanga as a “culinary heartland.”

Tantingco said rejecting culinary capital would be “ungrateful” to those who use that description. Using culinary heartland, on the other hand, compels Kapampangans to look at their cuisine in “a different light.”

“We shall assert that our cuisine is excellent, but it is not superior to the cuisines of other regions and provinces, even if in private, that’s what Kapampangans tell each other,” Tantingco said.

He considered the heartland to be uniting.

“For we belong to a nation of many different culinary traditions — different but equal, not one better than another. Every regional cuisine is the result of a combination of resources and experiences that are truthful, useful and unique to that community. Ilonggo cuisine, Ilocano cuisine, Bikol cuisine, Waray cuisine, Kapampangan cuisine — they are all colors of the same rainbow, just as our ethnic identities, our local histories and our local languages are merely the different fabrics of the tapestry of one national flag,” he said.

Views

Poet laureate Alvin Ignacio, also known as “Bertung Isponga,” started the conference by revealing the diversity and span of Pampanga’s cultural heritage when he recited the dishes and delicacies that towns and cities are famous for.

Richard Daenos, director of the Department of Tourism in Central Luzon, was certain in the status of Pampanga as a “significant culinary destination.”

Angeles City Mayor Carmelo Lazatin Jr. skirted the labeling and instead said that in Pampanga, “sharing food is an act of love.”

HAU president Leopoldo Jaime Valdes remembered times when food was nurturing and sisig was served without eggs.

Singapore-born Bryan Koh said he discovered that Kapampangans were “proud and passionate about their food” during his food research in the country, which he discovered from his Filipino nanny.

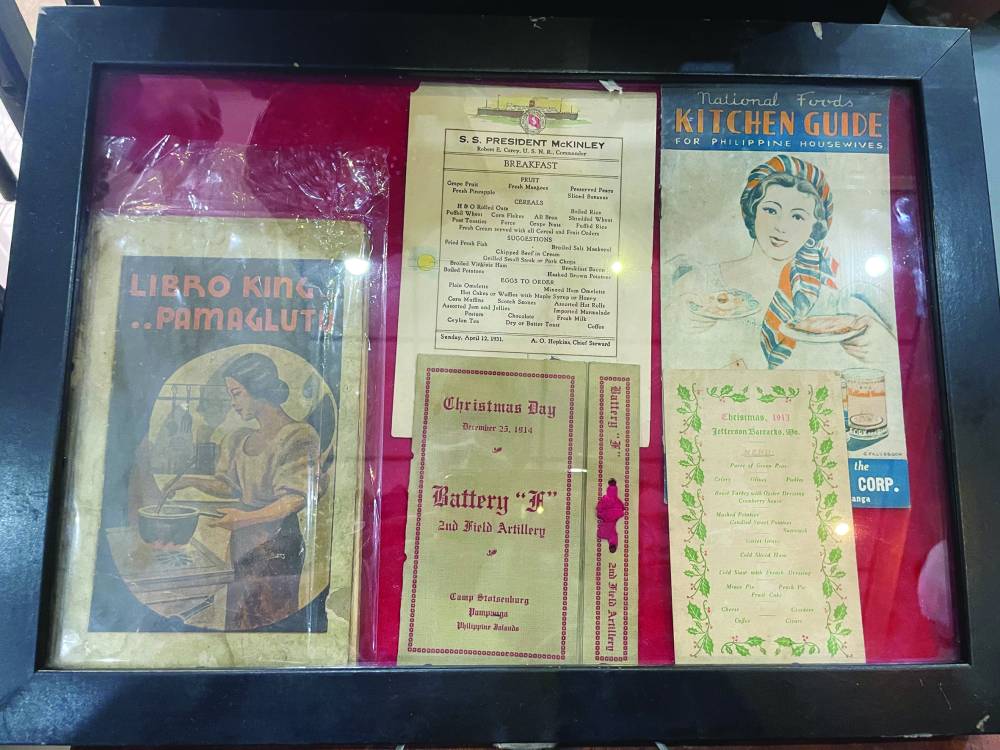

Sta. Maria donated a bagful of culinary research materials and spoke of three terms used or unique in the Kapampangan language as she found out in Fr. Diego Bergaño’s 1732 dictionary.

“Maliliag,” she said, refers to comfort food, while “malinamnam” relates to the best food. “Pasinaya,” which is also present in the Cebuano language, indicates hospitality.

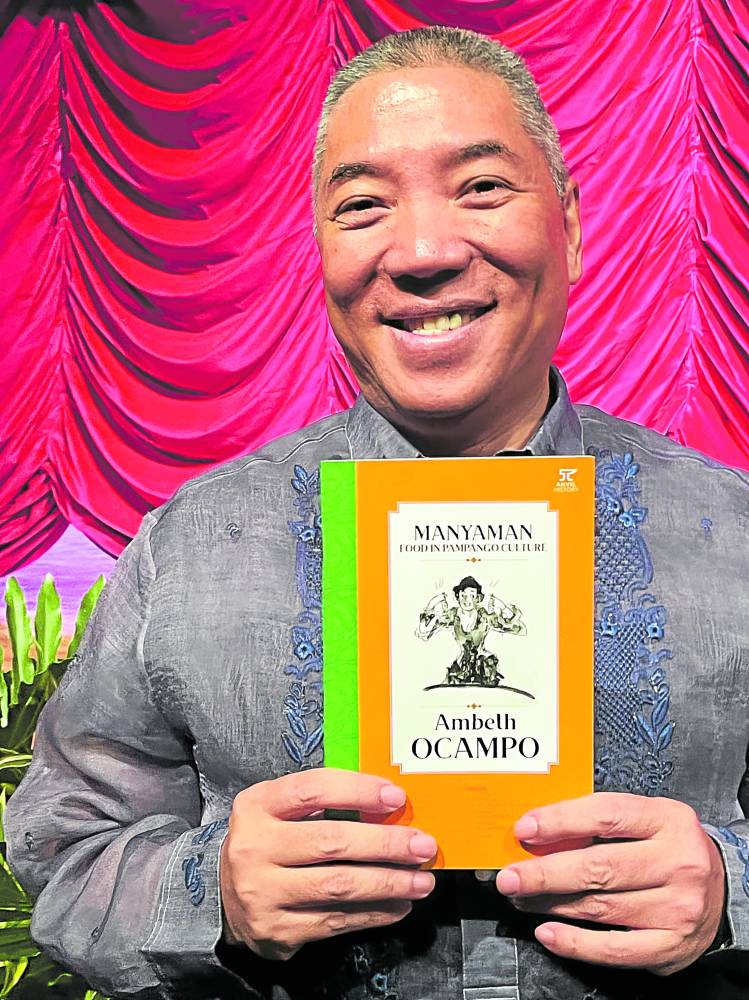

History professor Ambeth Ocampo, a Kapampangan, said, “Food shows us that we are not one history but many Philippine histories.”

“We should look, not just into Kapampangan food being what it is, but at the process. By taking the foreign would have made certain dishes Kapampangan. By taking the foreign we can make it our own and make it Filipino. Adaptation and indiginization, therefore, should be seen as patterns of resistance. People do not see things that way but you can see that it was our way of resisting what was foreign and creating an identity which is our own,” said Ocampo, who launched his book, “Manyaman (Food in Pampango Culture),” at the event.

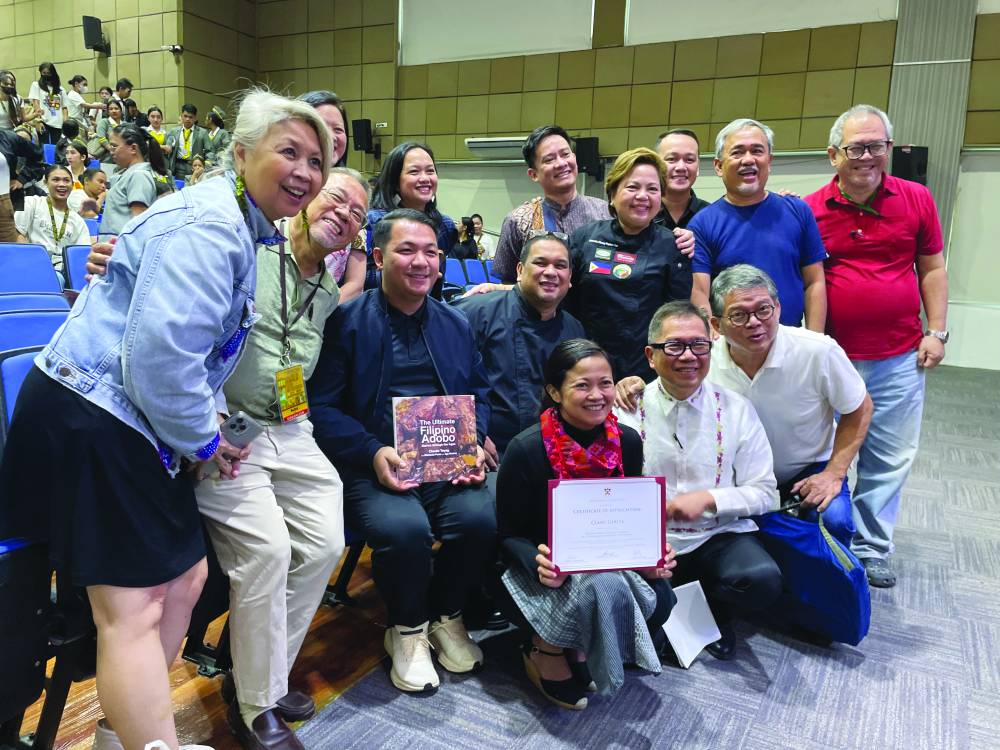

Chef Claude Tayag provided the historical perspective of why the culinary capital is inclined to be taken as fact rather than fiction. He included the point of view of Sta. Maria who, back in 1990, called Pampanga a part of the “Gourmet Highway.” The late writer, publisher and cultural icon Gilda Cordero Fernando described Pampanga in 1992 as “The Gourmet Province.”

Sulipan

Augusto Marcelino “Toto” Gonzales III revealed the quirks and pride of Pampanga’s landed gentry in the coastal town of Apalit where it concerned their cuisine. Who went to what wake on the basis of the food served at the funeral amused the largely young audience.

Tayag said that in the 1800s, Apalit’s Sulipan reached “the peak previously unattained by any other native cuisine in the archipelago.” That included attracting colonial-era visitors and foreign dignitaries.

The truth, Gonzales pointed out, was that colonial leaders scrimped and sent their guests instead to Sulipan.

Eugenio Ramon “Chef Gene” Gonzales, Toto’s brother, reconstructed the dinner of the 1898 Malolos Congress, with Sulipan workers and cooks overseen by Emilio Gonzales and Juan Padilla in preparing the items for the “great culinary feast” of the First Republic.

Bishop Pablo Virgilio David, president of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines, shared his thoughts on “tiltilan,” or the mixtures of sauces or condiments that enhance the flavor of food.

The dips, David said, spoke a lot about the adventurousness of the Kapampangan taste buds.

Based on his cooking and eating experiences, David said, “There is a thin line that separates the gourmands from the gourmets, the ‘matako’ (greedy eater) from the ‘manyaman a batal’ (someone who eats delicious food).”

“I do not mean to be a chauvinist, but I think we are mostly a combination of both,” the Kapampangan bishop added. INQ