Kapampangan language finds new life in liturgy

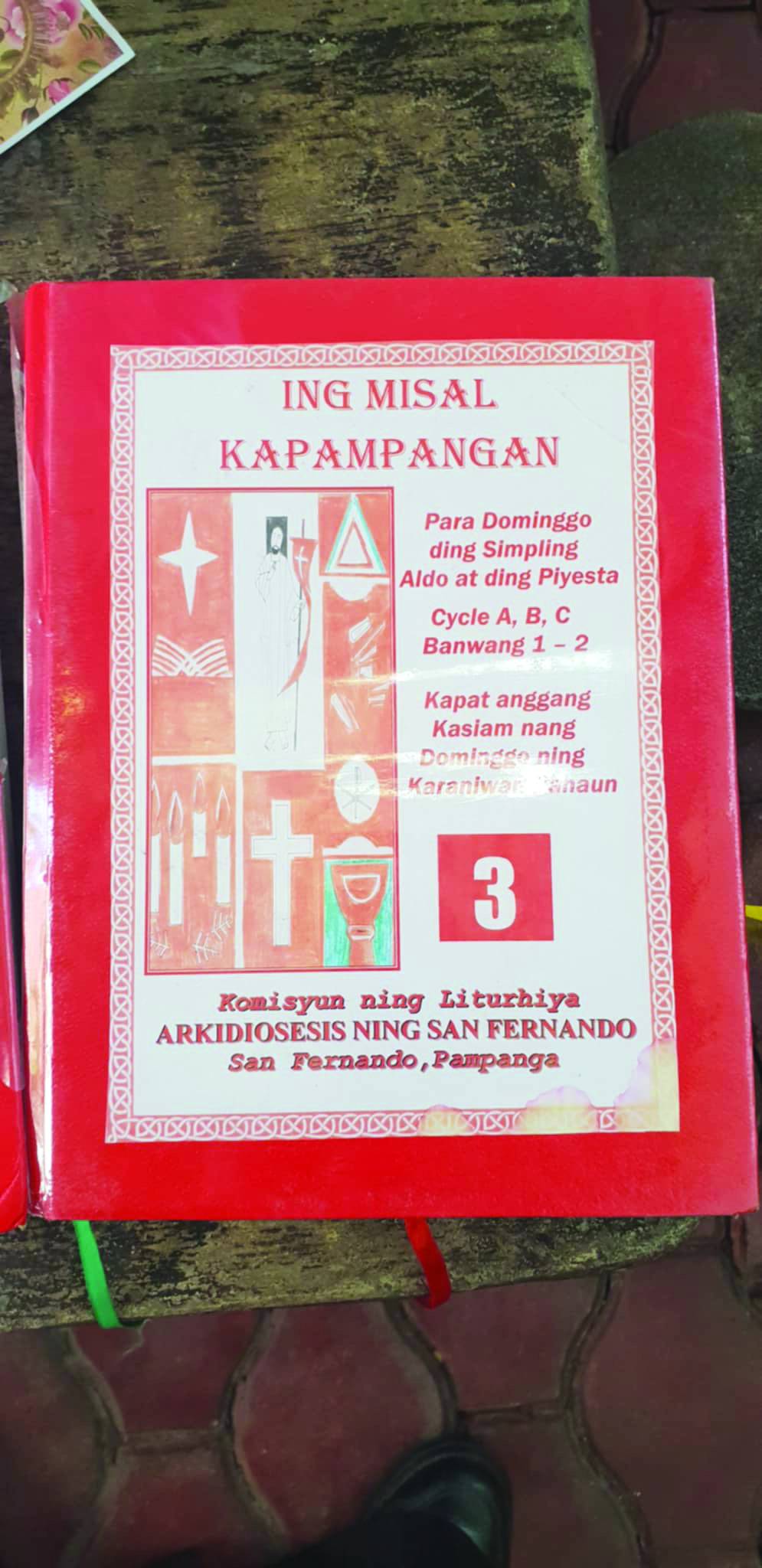

CITY OF SAN FERNANDO—The Kapampangan language has found new life in the liturgy, thanks to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of San Fernando (RCASF), which recently completed its vernacular translation of the Roman Missal’s third edition, originally published by the Vatican in 2002.

“At the heart of this change is the desire to draw the people of God to the liturgy and the liturgy to the people of God,” Archbishop Florentino Lavarias said in Circular Letter No. 51, issued on Nov. 24 last year.

“The adoption of vernacular languages in the liturgy takes into account the fundamental criterion of the participation of the people in the liturgical celebration,” he added.

Lavarias recalled that during his dialogues with villagers since becoming archbishop in 2014, the faithful expressed one firm conviction: they did not want the Mass removed from their lives.

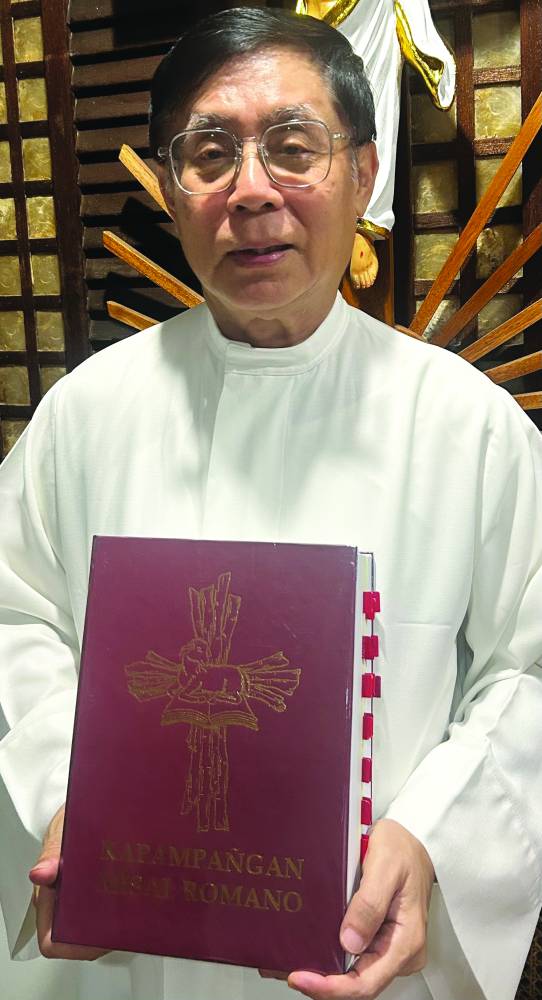

Msgr. Ricardo Serrano, director of the RCASF Commission on the Liturgy and lead translator of the new missal, said the book served two fundamental aspects of liturgy: the glorification of God and the sanctification of the faithful.

The new missal provides priests and celebrants with prefaces for Masses and sacramentals throughout the liturgical calendar—Advent, Christmas, Lent, Easter and Ordinary Time.

Commencement

It also includes guidelines on celebrating feasts or memorials of saints, whether obligatory or optional. The index begins on page 1,309.

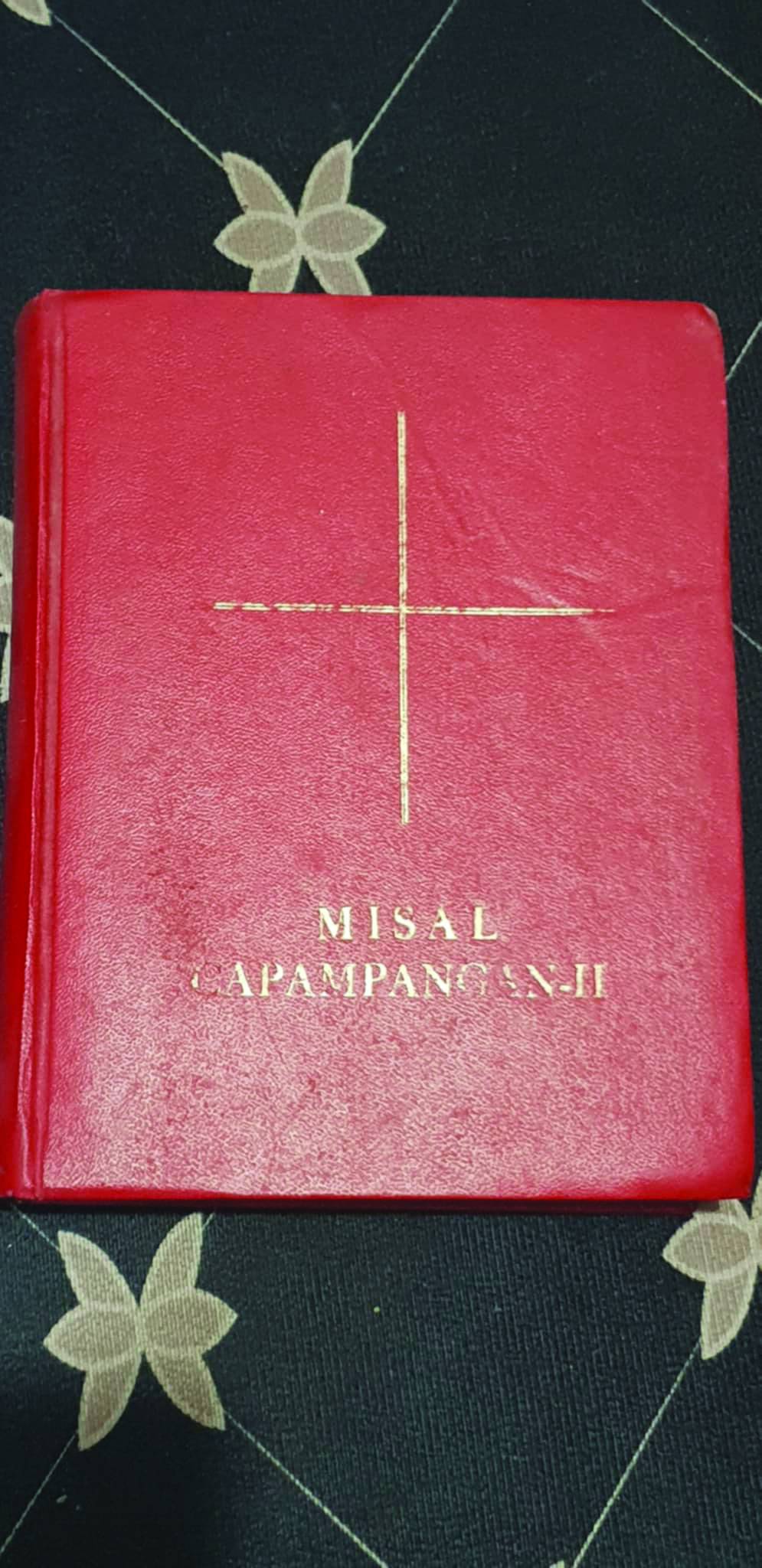

Lavarias decreed that the newest edition of the “Kapampañgan Misal Romano” will be used starting Ash Wednesday, on March 5.

“From that date, no other Kapampangan edition of the Kapampañgan Misal Romano may be used in the Archdiocese,” the archbishop ordered.

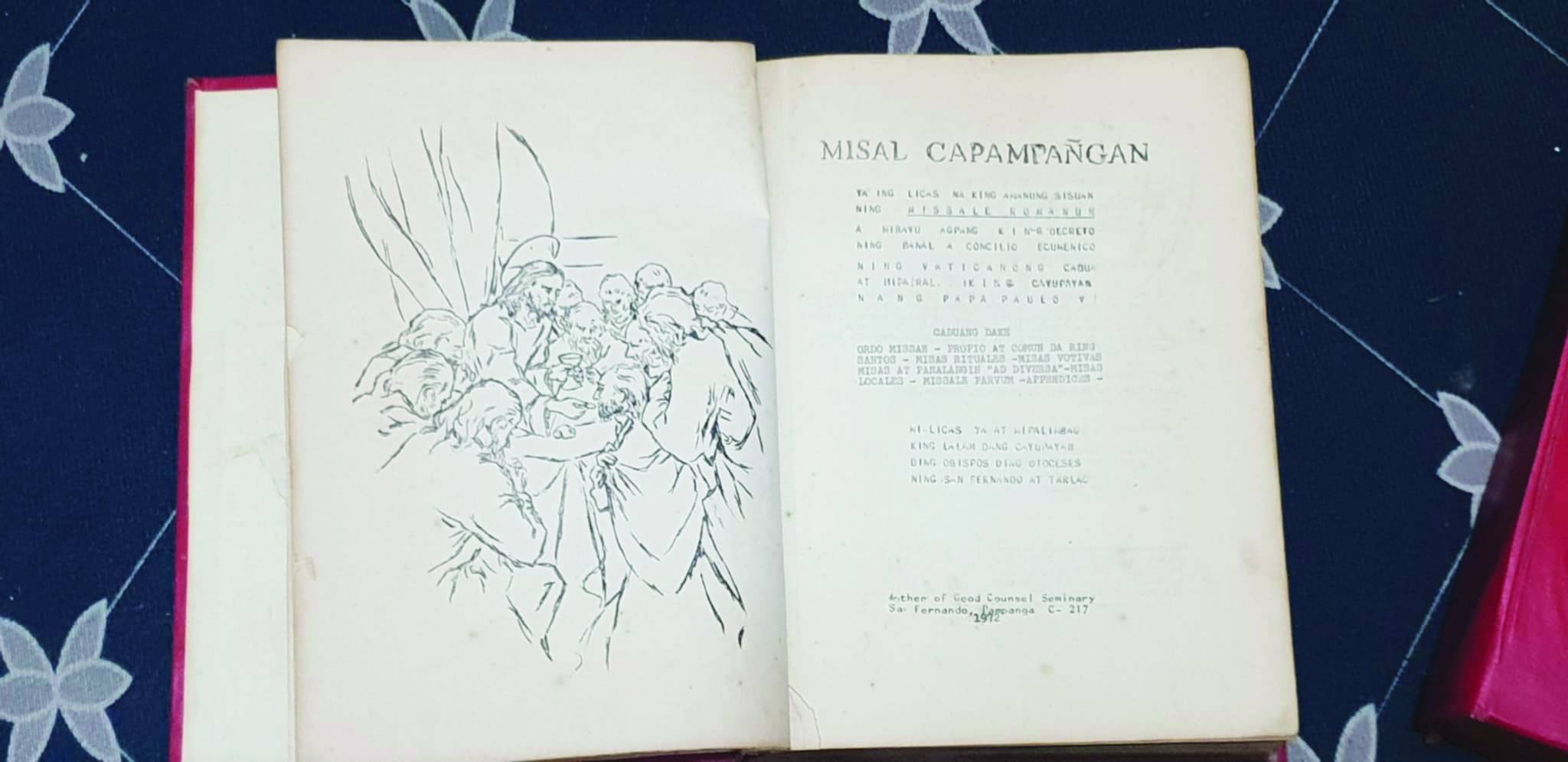

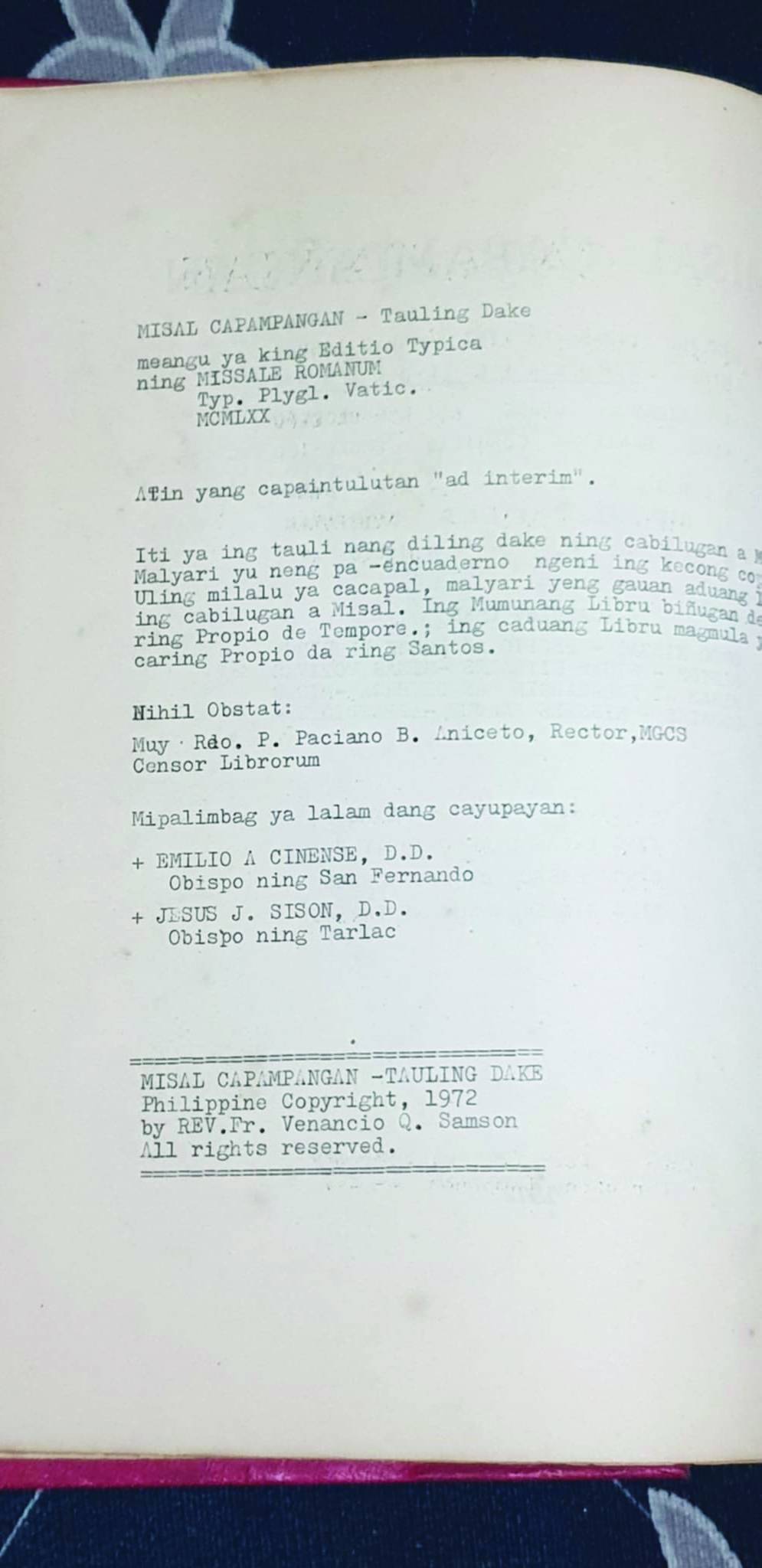

Before this, the translators of the second edition merely reproduced liturgical texts.

Hardbound and five inches thick, the third edition had 200 copies printed shortly before its launch on Nov. 28, 2024.

“We opted for a local printer, Mexico Printing Press, rather than having it printed in China,” Serrano said. However, these copies are not enough. The RCASF has 99 parishes, two shrines and 12 vicariates, each with hundreds of chapels.

The new project makes the archdiocese the “last bastion and refuge of the Kapampangan language,” said Robby Tantingco, executive director of the Center for Kapampangan Studies at Holy Angel University, the first Catholic school founded by a layperson, Juan Nepomuceno. Nepomuceno was among the second edition’s translators.

“With the dwindling number of Kapampangan speakers despite the region’s growing population, a Kapampangan-language Mass is most welcome. For generations, the Catholic Church has been one of the few domains where Kapampangan is spoken. But recently, there has been an increasing shift toward Tagalog-language Masses, as well as Tagalog sermons and hymns, even when the rest of the liturgy remains in Kapampangan,” observed Michael Pangilinan, a Kapampangan cultural heritage advocate.

Declining use

For the past 45 years, the RCSAF has also promoted the language by publishing “Ing Mayap a Balita” (The Good News), a monthly news magazine.

Despite these efforts, the use of “amanung sisuan” (the mother tongue) continues to decline.

Tantingco attributes this to schools, government offices, the courts and professional organizations prioritizing English and Filipino.

As the first and last bastion of the Augustinian Order, the early friars documented the language and translated it into Spanish.

Fray Francisco Coronel produced the Kapampangan grammar book “Arte y Reglas de la Lengua Pampanga” in 1617, just 46 years after Spain established Pampanga as its first province in Luzon. Other significant linguistic works include Fray Alvaro de Benavente’s “Arte y Diccionario de Pampanga” (1700) and Fray Diego Bergaño’s “Arte de la Lengua Pampanga” (1729) and “Bocabulario de Pampanga en Romance y Diccionario de Romance en Pampanga” (1732).

More recently, lexicographers have continued the work of preserving the language, including Joel Pabustan Mallari (2024), Bliezl Angelique Roldan-Sagmit and Ellalane Roldan-Sagmit (2017), Anicia H. Del Corro et al. (2012) and Fr. Venancio Q. Samson (2011).

Samson’s “Saldugan Capampangan para caring Capampangan: Diccionariong Capampangan para caring Capampangan” remains unpublished, despite being considered a comprehensive Kapampangan dictionary.

Serrano assured that the third vernacular edition of the missal was “faithfully and accurately prepared from the Latin text.”

Asked why it took over two decades to produce, he admitted, “Many objected to the translations (dakal mag-object king translations),” though no formal complaints were filed.

The Second Vatican Council (Vatican II) restored the practice of celebrating Mass in local languages, ensuring that the faithful could fully understand and participate in the liturgy.

This latest translation was not reviewed by linguists or heritage advocates, but Serrano defended the approach.

“We used computers to write and edit, allowing us to refine the text more efficiently,” he said. He also opted for widely understood words, choosing “mipagtaksilan” (betrayed) over the archaic “mipanganyaya.”

“The main goal is comprehension,” he stressed. “In the final analysis, the translation must enable the people’s active participation in the liturgy. That is the hallmark of liturgical reforms.”

Recognizing that many terms from Bergaño’s 1732 dictionary are no longer in use, the latest edition includes a primer and instructional videos for the laity. Serrano believes the faithful in rural villages (“baryu”) will adapt easily to changes, such as replacing “Espiritu Santo” with “Banal a Espiritu.”

Some areas in the dioceses of Balanga (Bataan), Iba (Zambales) and Tarlac (Tarlac), which fall under the RCASF’s jurisdiction, still have Kapampangan-speaking communities.

Serrano adhered to what he called “threefold fidelity”—to the original Latin text, to the Kapampangan language and to the comprehension of the celebrants and the faithful.

Challenge of translation

“Translation is a formidable task,” said Fr. Genaro Diwa, executive secretary of the Episcopal Commission on Liturgy of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines. “In this case, Latin was the reference point.”

Diwa emphasized that local languages such as Kapampangan, Tagalog, Ilocano and Cebuano “are not less dignified than Latin.” Once approved by the local Church, he said, vernacular translations hold equal footing with the original Latin text. “All languages, when used in faith, are sacred.”

Serrano underscored the importance of the missal: “After the Bible, this book is the most important. Munye ya kapanyamban king Dios (It will give glory to God) at manatad kabanalan kareng tau (and lead to the sanctification of the people).”

Pangilinan, however, urged caution. “The translation must remain faithful not just to the Latin text but also to the cultural identity of the Kapampangan people,” he said.

He noted that Kapampangans typically omit the polite particle “pû” when addressing God during Mass. “This makes it seem as if we are commanding God rather than humbly petitioning Him.”

Some priests have begun incorporating “pû” into prayers, even though it does not appear in the Latin text.

With the release of the Kapampañgan Misal Romano’s third edition, the archdiocese hopes to reaffirm its commitment to preserving both faith and language—ensuring that Kapampangan remains a living, spoken tongue for generations to come.