Labor rights are human rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights—adopted in 1948 by the United Nations General Assembly to set a framework for the pursuit of human rights globally—recognizes workers’ rights as essential to human dignity, equality, and freedom.

Article 23 of the Universal Declaration enumerates the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favorable conditions of work, and to protection against unemployment. It also includes the right to equal pay for equal work; the right to the enjoyment of just and favorable conditions of work, like fair wages and a decent living for themselves and their families; and the right to form and join trade unions.

Article 20 also guarantees the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association, and Article 24 states the right to rest, leisure, and reasonable limitation of working hours and holidays with pay.

ILO beginnings

According to the book “The International Labor Organization (ILO) and the quest for social justice, 1919-2009,” way before the 1948 adoption of the universal human rights framework, workers had already been organizing throughout the tail end of the 19th century, as social conflicts increasingly shifted to the workplace due to exploitation and economic inequality. As populations of workers flowed from agriculture to industry, they organized and demanded dialogue, opportunity, decent incomes, and dignity.

These movements were early to internationalize, as with the formation of the International Working Men’s Association in 1864, which brought together trade unionists and political activists to fight for the protection, advancement, and emancipation of the working classes, leading to what became known as the First International and the subsequent Second International in 1889.

The 1886 Haymarket Affair in Chicago, Illinois, also marked history for workers all over the world. Some 35,000 workers walked off their jobs, followed by tens of thousands more in the following days, to ignite a national movement for an eight-hour workday. The events inspired workers around the world to celebrate May 1 as the first international workers’ day.

These conditions, alongside rapid industrialization, wars, and revolutions—particularly after World War I from 1914 to 1918 and the Bolshevik revolution in Russia in 1917—prompted political leaders to pursue lasting change in politics, economy, and society, and to build international institutions that could engage all countries in a common effort.

It was against this historical backdrop that the ILO was created in 1919 as a means to address the cries for social justice and higher living standards for the world’s working people. As an effort “to promote social progress and overcome social and economic conflicts of interest through dialogue and cooperation,” the agency brought together workers, employers, and governments at the international level in search of common rules, policies, and behaviors from which all could benefit.

Conventions

One of the ILO’s major tasks has been the adoption of international labor standards, called Conventions and Recommendations, for implementation by member states.

The first such Convention set limits on industry working hours to eight hours a day and 48 hours a week. The second Convention was the ILO’s first attempt to tackle the problem of social protection, particularly when it comes to unemployment.

The third standard aimed to guarantee basic paid maternity leave for women for up to six weeks before their confinement and another mandatory six weeks after giving birth. The ILO also forbade the employment of women between 10 p.m. and 5 a.m. as an important protective measure in 1919, an era when gender equality was still a very distant goal.

The same protections were extended to children with ILO’s fifth and sixth Conventions. The former forbade employment to children under the age of 14 in industries such as mining, manufacturing, construction, and transport. Meanwhile, the latter banned night work for workers under the age of 16, though it was allowed in certain industries for workers under 18.

By 1970, 134 Conventions and 142 Recommendations had been adopted by the ILO. Apart from setting standards, they also addressed questions of basic human rights, such as freedom of association, collective bargaining, the abolition of forced labor, the elimination of discrimination in employment, and the promotion of full employment.

Treaties and covenants

Efforts for a more humane workplace were laid out in other human rights conventions and treaties like the Universal Declaration, the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organize Convention No. 87, also adopted in 1948, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights in 1966.

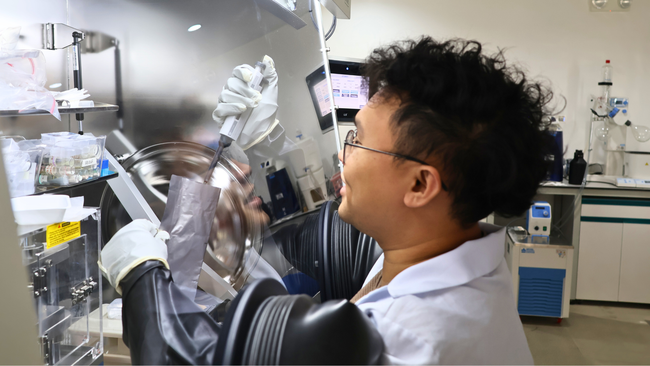

In the United States, occupational health and safety truly began only in 1970 with the passing of the Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) Act under the late President Richard Nixon. This act gave the federal government the authority to set and enforce safety and health standards for most of the country’s workers, improve safety and guarantee safer working conditions for all workers, and address issues related to known health and safety hazards, such as unsanitary conditions, cold and heat stress, and environmental toxins.

The Philippines formulated its own occupational safety and health standards—considered a landmark labor and social legislation—in 1978. It was formed through a tripartite consultative process involving government, workers, and employers, and has hence been used as a tool to protect workers from work-related hazards and risks.

Today, governments, companies, employees, and everyone else actively involved in human rights at work use these labor standards and treaties as important benchmarks for new policies and developments affecting workplace standards. They are the products of the long and hard-won struggle by people everywhere for just and fair working conditions, and must continue to be protected as vital guardrails in the pursuit of economic progress.

As ILO reiterated in the 2022 Report of the Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations, “Nowhere more than in the world of work—the sphere of human activity driving social and economic progress—must human rights be protected by the rule of law, including international labor standards, if ‘freedom from fear and want’ is to be realized ‘as the highest aspiration of the common people.’”

Sources: Inquirer Archives, ilo.org, un.org, tiki-toki.com, nobelprize.org, globalnaps.org, ehsinsight.com, dol.gov, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, ohnap.ph