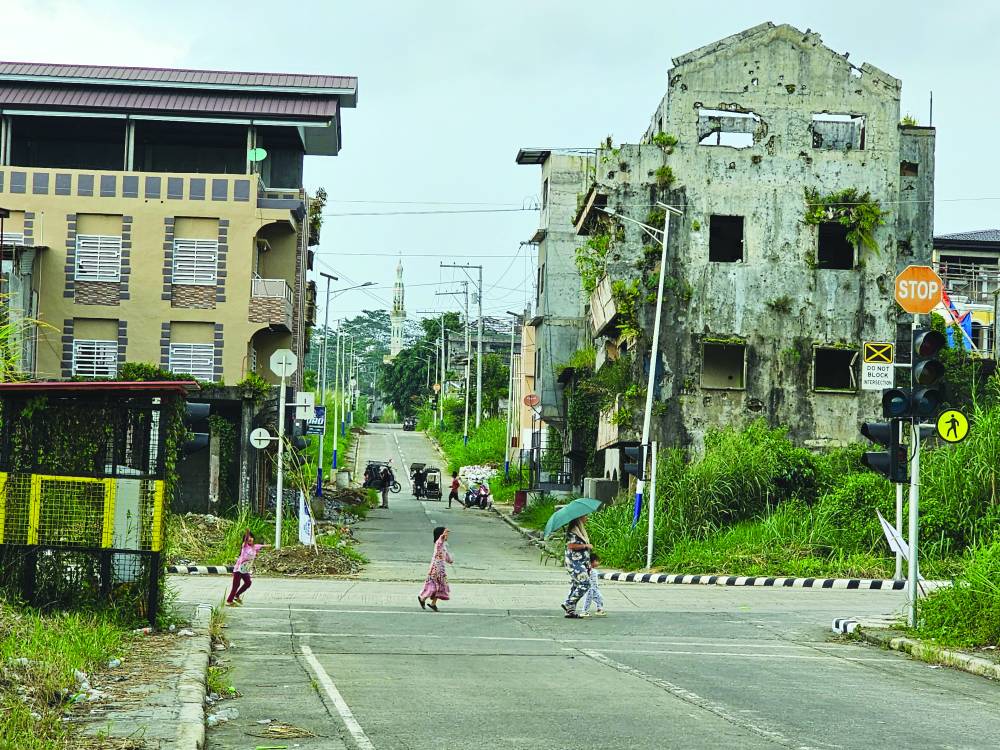

Marawi rises from ashes of war

MARAWI CITY—At the corner of a block in Sabala a Manao village here, businessman Bato Saripada, 63, supervised the clearing of grasses that had grown tall and took over what used to be a bustling commercial area.

They traced what remained of the column footings and walls of the two-story building on the 80-square-meter lot where Saripada’s family used to live and run a furniture store. “We actually operated five other stores in this area, all selling furniture items,” recalled Saripada, pointing to the grassy spots just across the now well-paved street where he rented space for his business.

Saripada’s rebuilding effort is funded by the proceeds of selling a house that his family owned in Iligan City, for P2.5 million, to a fellow Maranao trader who recently received compensation from the government for damaged structure and lost personal properties during the five-month war in 2017 triggered by a siege by Islamic State (IS)-linked militants.

“When my [compensation] claims for my house and lost inventory also come through, I can hopefully invest more,” he said.

Today, seven years after the militants led by the Maute brothers were driven out of the city, the major public infrastructure has already been established, within just four years after the projects broke ground. The rebuilding of homes and businesses would complete Marawi’s rise from the ashes of war.

The grant of compensation under Republic Act RA No. 11696, or the Marawi Siege Victims Compensation Law of 2022, is highly awaited to jumpstart a more aggressive pace of rebuilding the war-torn city, especially its once commercial district that encompasses 24 villages across an area of 250 hectares, known as the most affected area or MAA.

“We are committed to working tirelessly to help Marawi City rebuild and recover,” said a statement from the Marawi Compensation Board (MCB), the body mandated to oversee the compensation process, in commemoration of the seventh year of Marawi’s liberation from IS hands.

Resolved claims

As of Oct. 22, the board had resolved 1,111 claims amounting to P1.54 billion, or 77 percent of the P2 billion allocated by Congress for 2023 and 2024. Of these, P767.6 million had been paid out to 453 claimants as of Oct. 28.

This flow of funds is increasingly finding its way into the reconstruction of homes.

As of Aug. 30, the Office of Building Official (OBO) counted 3,741 building permit applications, up 54 percent from 2021, and 2,239 of these have been approved. Of these, 1,411 structures have undergone inspection for issuance of occupancy permit while repair or rebuilding is ongoing for 730 more. These are in the MAA, said engineer Mohammad Kassim Balang, OBO head.

Under RA 11696, the government provides compensation for deaths, damaged structures and other properties lost during the siege as a form of reparation. The properties claimed must be located in the 24 villages known as MAA, and eight known as the “other affected area.”

After a series of studies and consultations with experts, the MCB set the compensation for destroyed (“totally damaged”) properties at P18,000 per square meter if it was made of concrete, P13,500 per square meter if mixed concrete and wood and P9,000 if made of light materials or mainly wood. Damaged (“partially damaged”) structures will be compensated P12,000 per square meter if it is concrete, P9,000 per square meter if mixed concrete and wood, and P6,000 if made of light materials or mainly wood.

But according to the law, these amounts have to be compared to a fair market value of the property in question and the MCB has to choose the lesser amount to pay as compensation. This is why the MCB wanted a lone amendment to RA 11696, that is, dropping the need for a comparison of values in determining compensation for damaged properties.

Heirs of those who died due to the siege will be compensated P350,000, while personal properties, barring any documentary evidence, are pegged at 27 percent of the total value of a structure.

Property owners, and space sharers and renters are allowed to file claims.

When the yearlong application for compensation closed last July 3, the MCB received a total of 14,495 claims of which 192 were for deaths, 209 for structures damaged, 5,701 for other properties lost, and 8,393 mostly a mix of structure and other property claims.

The number of claimants is slightly lower than the 15,727 total families displaced from the MAA alone, per profiling of the Task Force Bangon Marawi in 2018. The MCB said this could be because some families, especially those renting or sharing spaces, had combined their claims with those of the property owners.

Priority

The MCB had prioritized the processing of death claims when it started out last year. The payout for this category of claims is almost done, leaving the body with the huge task of evaluating the claims for damaged properties.

According to lawyer Saliha Lalanto, head executive assistant of the MCB, claims are assessed on “what can be proven based on evidence” and the experience of Marawi presents a unique case. “Not many buildings have building permits, just like commercial establishments that have signages but do not have registrations with the Department of Trade and Industry and were not issued business permits [by the local government],” Lalanto noted.

“So, our [main] struggle is with evidence, proof,” she added.

This is partly helped by ocular inspections on what remained of the structures, to determine its age, character and nature, and then the extent of damage, said Lalanto, pointing to the big demand by the MCB for the services of engineers.

MCB lawyers also assess the proof of property ownership presented by claimants such as tax declarations, titles, deeds of conveyances and the like. “There is a general wisdom that if one is the lot owner, most probably he or she is also the owner of the improvements. But there are many nuances that must be probed in the case of Marawi,” Lalanto pointed out.

For one, there may be many structure owners within a single lot owned for instance by a clan patriarch who allowed his kin to build their homes within his property. This is ordinary among the Maranaos who are mostly close-knit and clannish.

The MCB is also on the lookout for property overlaps. Aiding its personnel are 3D maps, Google Earth maps before the siege and maps of the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority established before debris were cleared.

Settling disputes

Lalanto said they were grateful to the Office of the Presidential Adviser on Peace, Reconciliation and Unity for augmenting the MCB’s corps of lawyers and engineers.

The board, she said, makes sure that disputes among relatives are settled before claims are processed further, and for this, the MCB has tapped the services of traditional and religious leaders who hold strong sway among the locals.

After legal and technical evaluation, the claims are raffled off to the MCB’s three divisions, each with three members, who hold clarificatory hearings with claimants. The decisions of each division go up to the MCB en banc for final resolution. Approved claims are then published for 30 days to allow valid opposition to be raised before compensation is awarded.

The MCB had set to finish 200 claims per month. From August to October, it resolved 420 claims, or an average of 140 a month.

At this pace, the board can hope to finish the remaining 13,384 claims in 96 months, or eight years. With 43 months remaining in its institutional life that started on May 23, 2023, when the law’s implementing rules took effect, there may be a need to give the compensation process an additional four years so the MCB can satisfactorily wrap up its work.

“I have waited patiently, and can wait a little more. I do not expect that my claims, when approved, would bring back the property values I lost. But at least I could get a measure of justice for what happened,” Saripada said.

“And by then, I hope to build ahead of the others so I can position my business better,” he added.