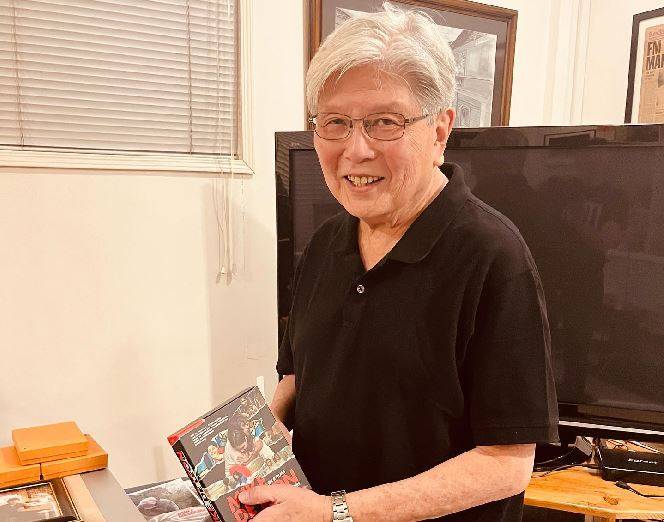

Master filmmaker Mike de Leon; 78

World-acclaimed filmmaker and archivist Miguel “Mike” de Leon, 78, passed away Thursday morning, Aug. 28, due to a lingering illness, his first cousin, designer Patis Tesoro, confirmed to the Inquirer.

News of De Leon’s passing was felt not only in the Philippines but as far as Europe, where he has been rediscovered in the past couple of years. The Paris-based Carlotta Films was among the first to pay its respects on social media. In 2022, it released eight films of De Leon in a Blu-ray box set, making these long-unseen movies now available in Europe and in the United States.

De Leon left behind a comparatively slim body of work, having directed only 10 full-length films. But today, they are considered among the greatest in the canon of Philippine cinema: “Itim” (1976), “Kung Mangarap Ka’t Magising” (1977), “Kakabakaba Ka Ba?” (1977), “Kisapmata” (1981), “Batch ’81” (1982), “Sister Stella L.” (1984), “Hindi Nahahati ang Langit” (1985), “Bilanggo Sa Dilim (1986), “Bayaning Third World” (1999), and, what would be his final work after a long hiatus, “Citizen Jake” (2018).

He also shot the short film “Aliwan Paradise” (1993), part of the four-country anthology film “Southern Winds.”

He was “a voice for the unheard, a visionary genius behind generation-defining cinematic classics who shone a light on the beauty and pain of the downtrodden and repressed, bringing their stories to the cultural forefront,” said the Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP) in its tribute.

LVN scion

De Leon was no outsider to cinema when he started. Born on March 24, 1947, he was the grandson of Narcisa “Sisang” de Leon, the matriarch and driving force behind LVN Studios, one of the country’s biggest movie production outfits in the postwar era.

De Leon received his bachelor’s degree from the Ateneo de Manila University and also took up art history at the University of Heidelberg in Germany.

In his two-volume photographic memoir titled “Mike de Leon’s Last Look Back,” published in December 2022, De Leon wrote: “Biologically, I owe my life to Lola/Grandma Sisang and my parents Manuel and Imelda. But as for my life in cinema, I owe it all to LVN.’”

De Leon got his start in the industry producing and serving as cinematographer of the Lino Brocka classic “Maynila, Sa Mga Kuko Ng Liwanag” (1975).

His first feature was the 1976 ghost story “Itim,” which was met with immediate acclaim.

In later films like “Batch ’81,” about a group of young men undergoing harsh initiation rites in a university fraternity; “Sister Stella L.,” about an apolitical nun waking up to the social realities around her; and “Kisapmata,” which tackled incest and crime in a rigid patriarchal home, De Leon used his cinema to shine a light on the brutality and oppression of the then Marcos dictatorship.

In “Last Look Back,” he noted how, in more than 45 years, he “only directed 10 feature films, produced three and photographed two.”

Aside from “Aliwan Paradise,” he did the short features “Sa Bisperas” (1972) and “Signos” (2008).

“Sa Bisperas” consisted of random shots of street rallies he had personally taken during the First Quarter Storm. But when martial law was declared, De Leon said he hid the film negatives so well that, years later, even he couldn’t find them.

“‘Sa Bisperas’ is lost forever,’” he said.

Two retrospectives

In 2022, De Leon’s filmography was honored with two landmark retrospectives: the monthlong “Mike de Leon, Self-Portrait of a Filipino Filmmaker” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, from Nov. 1 to Nov. 30; and at the 44th edition of Three Continents Festival in Nantes, France, from Nov. 18 to Nov. 27.

Ironically, no retrospective was ever held for him in the Philippines.

There had been clamor to confer on De Leon the Order of National Artist for Film, but in his twilight years he was known for turning down awards and shunning the limelight. In good humor, he told filmmaker Mel Bacani II, “maybe posthumous na lang.”

When the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) gave him the Gawad CCP Para sa Sining for Film in 2024, CCP vice president and artistic director Dennis Marasigan said De Leon had declined the award. But despite the rejection, the board still decided to honor him, along with his contemporary, screenwriter-poet Jose “Pete” Lacaba.

Digitized library

In his later years, De Leon digitized what was left of the LVN film library and shared them for free on his YouTube and Vimeo channels named “Citizen Jake.” In the Facebook page Casa Grande Vintage Filipino Cinema, which he had been curating since 2017, he wrote snippets about the golden years of LVN.

For film historian and book author Nick de Ocampo, “Almost every film he did is a masterpiece of that particular genre. He didn’t pander to any commercial demands. He really specialized in his vision … His films are the papyrus of our generation. It is time to study them and know what needs to be known.”

FDCP Chair Jose Javier Reyes, meanwhile, wrote: “[His] life was dedicated to film. His consistent imagination to explore the language of cinema shaped what we understand of Philippine filmmaking today.”