Palace: More cleanup of dirty money ‘mess’ left by Duterte

President Marcos will continue to “clean up the mess” left behind by his predecessor which led to the inclusion of the Philippines on a watch list of nations with poor countermeasures against the flow of dirty money before the country was delisted by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) last week, Malacañang said on Saturday.

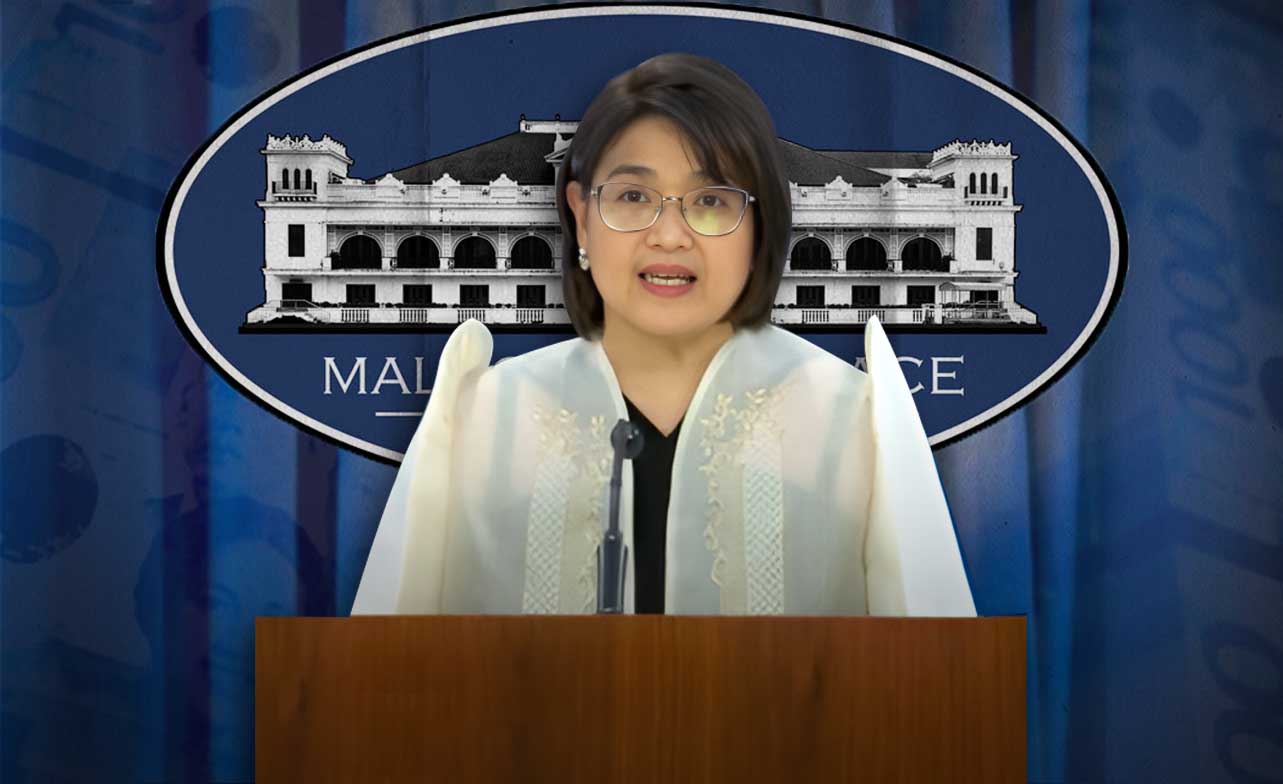

Presidential Communications Office Undersecretary and Malacañang press officer Claire Castro said the country’s removal from this “gray list” nearly four years after it was included by the FATF was a “big accomplishment” for Mr. Marcos.

On Feb. 21, the FATF removed the Philippines from its watch list after the country implemented corrective measures to address 18 deficiencies in its antimoney laundering (AML) and countering the financing of terrorism (CFT) systems.

FATF president Elisa de Anda Madrazo said that the Philippines would have to show that it could sustain its AML/CFT reforms in a way that was “consistent” with the standards set by the Paris-based dirty money watchdog, which placed the Philippines on the gray list in June 2021.

For OFWs, investments

“We—especially the President—can certainly clean up the mess left behind by the previous administration. Let us just pray that we can sustain our noninclusion in the FATF’s gray list or blacklist,” Castro said in a four-minute recorded video posted on Radio Television Malacañang’s Facebook page.

She repeated Malacañang’s statement that the country’s exit from the FATF watch list would benefit overseas Filipino workers as they would no longer need to pay large remittance fees. She added that the Philippines would also attract more foreign investors.

“The President will not stop in addressing these issues and stopping money laundering and terrorism financing activities,” Castro said.

She credited the President’s Executive Order No. 33 issued in 2023 that ordered government agencies to adopt the National Anti-Money Laundering, Counter-Terrorism Financing, and Counter-Proliferation Financing Strategy 2023-2027 to get the Philippines off the watch list.

Unimposed sanctions

“Because the President issued EO 33 to direct government agencies to undertake measures to have our country removed from the gray list, the FATF saw the Philippines’ improvements in money laundering and terrorism financing controls,” she said.

“This is such a big accomplishment for the President to have the Philippines removed from the gray list,” she said.

Castro pointed out that the Philippines’ inclusion on the watch list happened under President Rodrigo Duterte.

During the previous administration, there was a “lack of regulatory supervision” over gambling operations, she said, noting that the Philippine offshore gaming operations (Pogos) were “booming” at the time.

There was “weakness in the implementation of targeted financial sanctions” against irregular transactions, particularly during the pandemic, which were reported but “apparently ignored.”

In addition, there were delays in the implementation of the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 despite allocations of “huge amounts of intelligence and confidential funds,” Castro said.

The FATF said the Philippines should continue to work with the Asia-Pacific Group on Money Laundering “to sustain its improvements” in its AML/CFT system.

The FATF said the Philippines should continue to work with the Asia-Pacific Group on Money Laundering “to sustain its improvements” in its AML/CFT system.

“The FATF encourages the Philippines to continue its work in ensuring that its CFT measures are appropriately applied, particularly the identification and prosecution of TF cases, and are neither discouraging nor disrupting legitimate NPO (nonprofit organization) activity,” it said, referring to nongovernmental organizations (NGO) or civil society groups in the country.

At a steep cost

The National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL) said the delisting of the country came at the cost of widespread and indiscriminate crackdown on such groups, and development workers and human rights defenders who lost their “freedom and ability to serve the communities that need them most.”

This “achievement” of the Marcos administration was the product of “political repression” built upon allegedly fabricated terrorism financing cases, arbitrary asset freezes and financial exclusion.

It accused the government of using regulations meant to combat terrorism financing to “harass grassroots movements, all while failing to address large-scale corruption, illicit financial flows and the billions of pesos laundered” through Pogos.

NUPL and the Council for People’s Development and Governance said in a report that antimoney laundering and CFT laws were being “weaponized to suppress civil society organizations” and their activities “under the guise of compliance with FATF standards.”

Terrorism financing cases jumped from 14 in 2023 to 66 the following year, a 371-percent leap, NUPL said.

‘Climate of impunity’

Separately, the US-based Human Rights Watch (HRW) said the Philippines was filing terrorism financing cases against civil society groups and activists “apparently to be removed” from the FATF gray list.

“This seems to be the government’s latest bad reason to bring baseless charges against civil society groups and activists in violation of their rights,” said Bryony Lau, deputy Asia director at HRW.

The human rights group Karapatan said that the government’s efforts to remove the country from the gray list worsened the “climate of impunity” with the use of antiterror laws against more than 100 political dissenters and development workers.

To get off the dirty money list, Karapatan added, the government “prey[ed] on people’s organizations critical of the misdeeds of the government as well as developmental (nongovernmental organizations) that provide services to poor communities.” —WITH REPORTS FROM KATHLEEN DE VILLA AND INQUIRER RESEARCH