PH marine scientists offer another kind of ‘diplomacy’ in WPS row

If the generals and the diplomats are not always seeing eye to eye, how does one protect a highly disputed yet threatened marine ecosystem that’s become a flashpoint for geopolitical tensions?

Maybe it’s up to the men and women of science to see past the acrimony and agree on common grounds.

For some of the country’s leading marine experts who study the West Philippine Sea (WPS), it means moving beyond political boundaries to push for a more collaborative, cross-regional effort to protect the biodiverse-rich area.

It could mean, for example, establishing marine protected areas (MPAs) that can be jointly managed by members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) who have overlapping maritime claims. It could also mean more scientific cooperation among scientists who also monitor the area.

But one thing is for sure: isolating China from larger efforts to conserve and protect the WPS is “not an option,” according to the Filipino marine scientists at a recent forum on “science diplomacy” at the University of the Philippines’ (UP) Center for Integrative and Development Studies.

Deo Onda, Wilfredo Licuanan and Charina Amedo-Repollo agreed it would be counterproductive to just engage in finger-pointing as to who was responsible for the documented destruction of coral reefs in the WPS “when we’re not doing a good job ourselves.”

China and the Philippines have recently engaged in a blame game over who has wrought the most serious or widespread destruction on the bigger South China Sea, of which the WPS is part, a waterway almost entirely claimed by Beijing.

Strategy needs data first

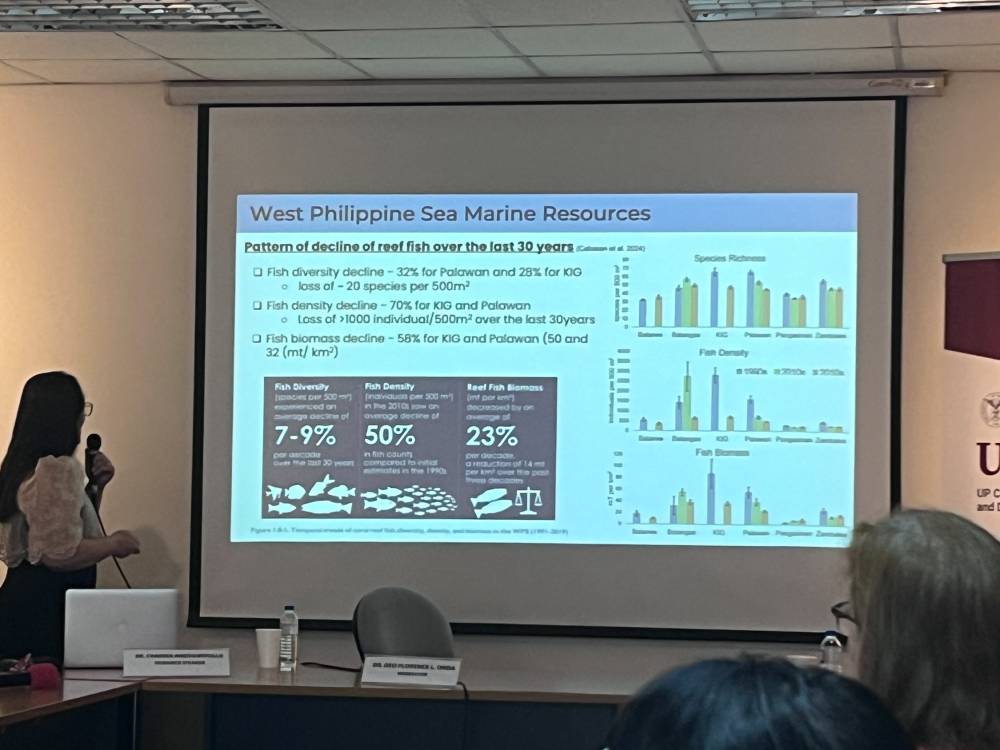

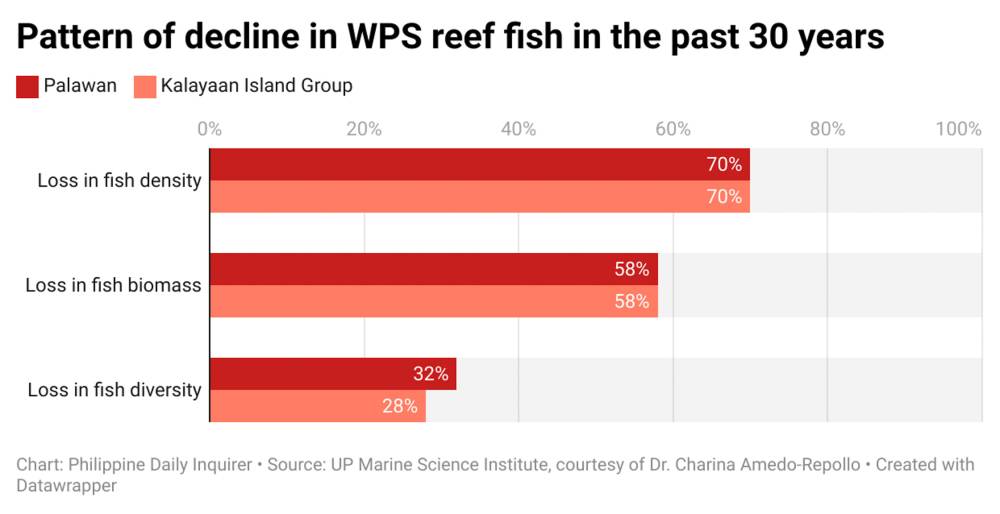

China continues to disregard the historic 2016 arbitral ruling that voided its sweeping claims and upheld Philippine sovereign rights over the WPS, area designated by Manila to mark its exclusive economic zone.The WPS, a traditional fishing ground for Filipinos, is estimated to account for about a third of the country’s total fisheries production, Repollo said.

Repollo and Licuanan said that while it was true that China’s construction of artificial islands had destroyed vast swaths of coral reefs, the Philippines’ lack of long-term, comprehensive monitoring and centralized databases on coral reefs and marine life in the WPS and other areas had not helped its case, either.

This, Onda said, had hampered the country’s ability to craft “management strategies [or] come up with mitigation and management frameworks as we do not know what the (marine) resources are.”

While there have been hundreds of surveys of coral cover in the area—many led by the UP Marine Science Institute since the 1980s—Licuanan said “we’re not collecting enough in terms of other important information … and even if there is a need and interest in collecting that data, the resources are not used as they should be.”

“Coral reef management in the Philippines is falling (through) the cracks,” said Licuanan, a biologist and university fellow for De La Salle University. “How can we claim to be managing our reefs when we’re not even monitoring it, or the data is not ending up in a central repository?”

The experts also noted the lack of a broader conversation on the WPS, where much of the focus has been on security and not on its value as one of the world’s most biodiverse and productive fishing grounds.

In a report he authored and released in 2019, Onda estimated that the Philippines had been losing about P33.1 billion yearly since 2012 from the damage on reef ecosystems, particularly at Panatag (Scarborough) Shoal and the Spratlys Islands, mainly due to China’s reclamation activities and illegal fishing operations. The amount represented lost “benefits” in terms of fish catch, habitat health and climate regulation, among others.Opportunities

Still, there are opportunities to close the gap in marine conservation in the WPS, said Repollo who is currently part of a team helping the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) designate MPAs in the Kalayaan Group of Islands (KIG).There are about 300 MPAs marked by the government across the entire stretch of the West Philippine Sea but none anywhere near the KIG, an area under the jurisdiction of Palawan province, partly because of the overlapping territorial claims, Repollo said.

“But it’s possible to establish MPAs there,” she said. “It was a belated effort (by the DENR), maybe because we were not aware before that the WPS contribution to our economy was really that big.”

She does, however, acknowledge the challenge of securing this would-be MPA in the Kalayaan group using civilian enforces like the Bantay Dagat patrols.

“And if China happens to push back on that, that’s going to be a problem,” Repollo said. “That’s why we have to sit together especially now that they’re also pushing supposedly for environmental protection.” INQ