PH wartime heroes get honors from US

BAGUIO CITY—The first bomb unleashed over the John Hay Air Station by Japanese fighter planes on Dec. 8, 1941, was heard 3 kilometers away from Teachers’ Camp, where cadets of the Philippine Military Academy (PMA) were attending classes at the time.

The instructor assured the cadets that the explosion could be part of a routine drill by American soldiers stationed in that military base in the city.

But subsequent explosions signaled the start of the Pacific War for the Philippines during World War II.

Siblings Magtangol and Mapagtapat Ongchangco were immediately deployed to Manila to be commissioned as junior military officers along with their classmates of PMA Classes 1942 and 1943. They were the only set of cadets in modern history to graduate early and lead the fight against the invading Imperial Japanese Army.

The Ongchangco brothers were honored posthumously with United States Congressional Gold Medals along with 42 other war heroes at a ceremony on Sept. 3, raising the number of its Filipino recipients to 1,096.

The US Congressional Gold Medal Awards celebrate “not just the individual acts of our heroes but also the collective spirit of a generation that fought for a better world,” Defense Secretary Gilberto Teodoro Jr. said in a speech read for him by Philippine Veterans Affairs Office Administrator Reynaldo Mapagu at the Baguio Convention and Cultural Center.

“It is our turn to defend our independence,” Teodoro said.

This was the 34th ceremony since the medals were first given to Filipino war veterans in 2017.

Women among veterans

Eleven of the 44 heroes who received the medals are still alive, and all but one stayed home due to Tropical Storm “Enteng” (international name: Yagi).

Retired Sgt. Eumelia Cacanindin, now 99 and wheelchair-bound, received her medal from Mapagu, Mayor Benjamin Magalong and KevinMcAllister, the US Embassy’s assistant director at the Manila Regional Benefit Office of the US Department of Veteran Affairs.

Many of the veterans who were honored were women, like Privates Estrella Nares, Ester Fe (97 years old), Regina Oreiro (100) and Constancia Nones (101), who treated the wounded and were in charge of logistics that fed and armed the guerrillas.

Some of the oldest living war heroes served as spies.

Retired Sgt. Antonia Sanches, 98, was sent to monitor enemy activities. Retired Pvt. Virgilio Costales, now 100 years old, served as a courier who transmitted enemy movements to guerrilla units as a member of the United States Armed Forces’ Land Communications Service Company. Retired Sgt. Martin Lubrin, also a century old, took part in ambushes and sabotage operations against the Japanese.

Councilor Betty Lourdes Tabanda, one of the 11 children of the late Maj. Alfredo Flores, a survivor of the Bataan Death March who was honored here, said her father had just completed a mining engineering course when he joined the Japanese resistance.

She said Flores fought to stay alive at a detention camp in Tarlac province “because he could not allow his family and the families of fellow soldiers to go through such a despicable situation [as an occupied country].”

Call of duty

The Ongchangco brothers best portrayed how PMA cadets responded to the call of duty.

Mapagtapat, who was a 22-year-old first class cadet, was supposed to graduate in 1942 along with 70 of his mistah (classmates) when war broke out.

He and Magtangol, a second class cadet and older at 24, graduated early and were sent home for what would have been a 10-day break, according to family archives and video interviews of Mapagtapat, which were recorded by the Ongchangco children.

But five days later, all 71 members of Class 42 and 60 members of Class 43 were recalled to Manila to receive their ranks as third lieutenants on Dec. 13, 1941, at the University of Santo Tomas.

Mapagtapat commanded 110 enlisted men and four officers when he was posted at Mt. Samat in Pilar, Bulacan.

Dwindling supplies and the unending Japanese onslaught forced Mapagtapat’s unit to surrender on April 12, 1942. They were part of the Death March and were jailed at a concentration camp in Capas, Tarlac, where Mapagtapat reunited with Magtangol. The brothers struggled with malaria while under detention.

One of Mapagtapat’s children said their father found the strength to feed himself tutong (burnt rice) from the scraps of their captors after witnessing the priest beside him wither away at the concentration camp.

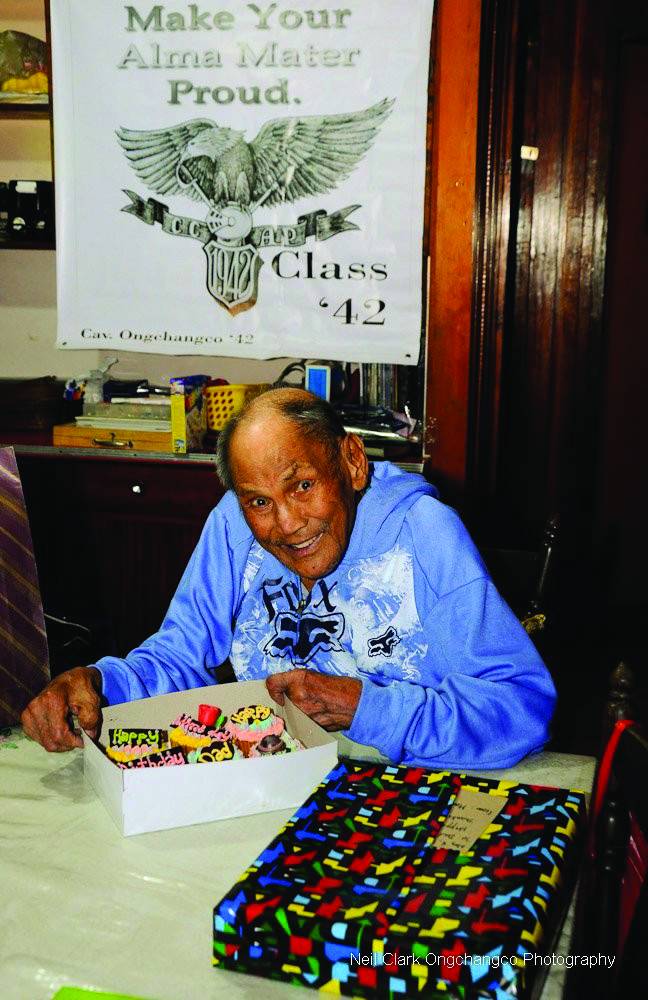

After the war, Mapagtapat served as the PMA Dean of the Corps of Professors from 1963 to 1968. He died at the age of 92 on May 26, 2011. Magtangol served during the Korean War and died on Feb. 14, 2002, a month before he would have turned 85 years old.

Strategic

The 34th awards ceremony was staged on the day, 79 years ago, when Japanese Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita “ended war in our motherland,” by signing his surrender papers at Camp John Hay. The timing symbolized Baguio’s “pivotal role in the country’s most brutal war,” Teodoro said.

He said the city suffered “the opening salvo” of the Pacific War for the Philippines during World War II. Japanese bombers attacked Camp John Hay a day after laying waste to the American Naval Base in Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, which drew the United States into the global conflict against the Axis Powers, a coalition headed by Germany, Italy and Japan.

Yamashita had retreated to Baguio in the last months of the war and was cornered by Filipino guerrillas and American and Filipino soldiers in Ifugao province on Sept. 2. He was returned to Baguio to formalize his surrender.

University of the Philippines scholars said Baguio may have actually been a target because of the presence here of the John Hay Air Station and the PMA.

The city was also the gateway to the country’s oldest mines in Benguet, which Japan sequestered in order to build up its munition supplies.

To liberate the city built by the American colonial government, American bombers destroyed most of Baguio, leaving only the Baguio Cathedral standing.