Pork scam postmortem: Big fish mostly getting away

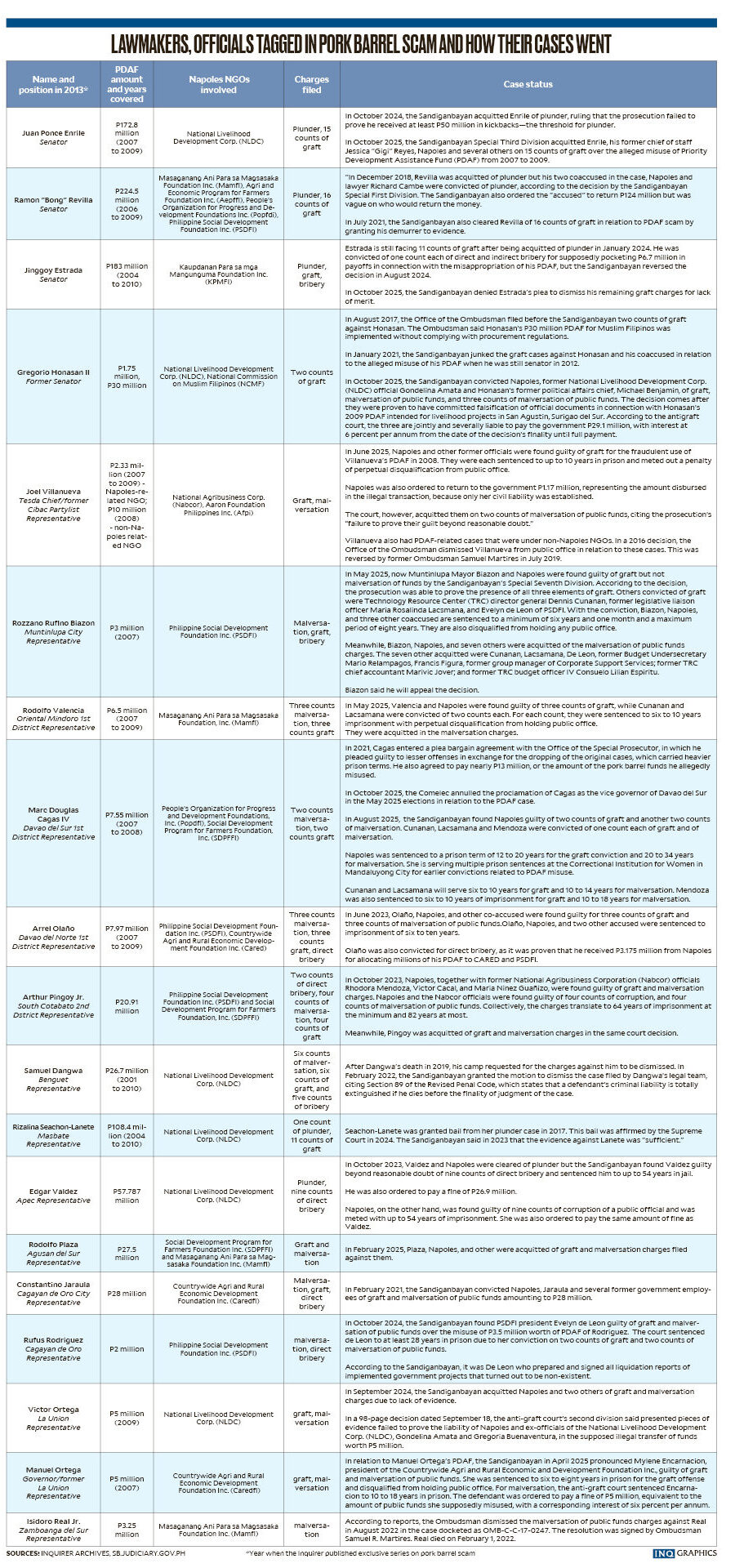

The recent acquittal of former Senate President Juan Ponce Enrile and 34 other individuals of 15 counts of graft

in the P10-billion pork barrel scam has renewed fears among Filipinos that the same slow-paced justice could doom the quest for accountability in the half-trillion-peso flood control corruption scandal and let those behind it go unpunished.

According to University of the Philippines constitutional law professor Paolo Tamase, one of the biggest and “critical” lessons that must be learned from the Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF), or pork barrel scam, is that the longer a case is prosecuted, the more likely it ends in acquittal.

“Long cases like these often weaken with time,” Tamase told the Inquirer in a phone interview. “Witnesses tend to forget (details of) the cases, prosecutors change, documents get lost—and what looks like a strong case in the beginning slowly fades into dust.”

The Office of the Ombudsman, which filed charges against lawmakers linked to the scam about a decade ago, has lost its PDAF cases for plunder against Sen. Jinggoy Estrada and former Senators Ramon “Bong” Revilla Jr. and Enrile.

Estrada was convicted of direct and indirect bribery, but the Sandiganbayan later reversed its decision. He is facing 11 separate cases of graft.

Revilla and former Sen. Gregorio “Gringo” Honasan II were charged with graft but were also acquitted.

Several members of the House—Representatives Rizalina Seachon-Lanete, Samuel Dangwa, Rodolfo Plaza and Constantino Jaraula—had been charged with plunder. All, except for Seachon-Lanete were acquitted. She is appealing her conviction.

Former Muntinlupa Rep. Ruffy Biazon was convicted of graft. He is serving as mayor of Muntinlupa City while appealing the decision. Former Davao del Sur Rep. Marc Douglas Cagas IV pleaded guilty to lesser charges of fraud and falsification of public documents in relation to the misuse of his pork barrel.

Over a hundred charged

According to figures from Inquirer reports, at least 112 officials, most of them lawmakers at the time, were charged with plunder and graft for misusing PDAF—38 in September 2013, 34 in November 2013 and 40 in August 2015.

Under the law, plunder is committed when the offender amasses ill-gotten wealth totaling at least P50 million in public funds from a series of acts, while graft is a broader offense by public officers who abuse their position for personal benefit.

Businesswoman Janet Lim Napoles, the alleged mastermind of the PDAF scam, has been convicted in about a dozen cases, including one for plunder, since the pork barrel racket was exposed by the Inquirer in 2013.

In most cases, acquittals in the plunder and graft cases related to the pork barrel scam were due to “weak evidence” presented by the prosecution.

In the case of Revilla, the Sandiganbayan said in its December 2018 decision that the prosecution did not establish “beyond reasonable doubt” that he directly or indirectly received commissions or kickbacks from his PDAF. It said that his supposed signatures in letters authorizing the funneling of his pork to Napoles’ foundations were forged.

However, Revilla’s legislative officer, Richard Cambe, and Napoles, were convicted for pocketing P124.5 million from his pork barrel funds.

In Estrada’s case involving P183 million of his PDAF, the prosecution accused the senator of amassing up to P55.79 million from his pork barrel, aside from being “an active participant in the conspiracy to commit plunder.”

But the Sandiganbayan acquitted Estrada and Napoles in January 2024, ruling that the prosecution wasn’t able to establish the strength of its evidence against them.

Deliveries not detailed

In October 2024, the Sandiganbayan acquitted Enrile of his P172.8-million plunder case, after prosecutors failed to show that the kickbacks he allegedly received from his pork barrel when he was a senator reached the P50-million threshold.

The antigraft court also acquitted his former chief of staff Jessica Lucila “Gigi” Reyes and Napoles.

In its ruling, the Third Division of the Sandiganbayan said none of the prosecution witnesses testified that they had “handed or transferred money to Enrile himself” despite allegations that he and Reyes “repeatedly received” kickbacks or commissions from Napoles or her representatives.

It said that there were only five transactions that were alleged disbursements of kickbacks for Enrile and these totaled P46.39 million, below the plunder threshold.

The deliveries of funds to Reyes, supposedly intended for Enrile, were also never detailed, the court said.

The Special Third Division of the antigraft court made similar statements when it acquitted Enrile, Reyes, Napoles and their 32 coaccused of 15 counts of graft last week.

The court said there was “clear lack of evidence” proving that the 101-year-old ailing presidential legal counsel had received any form of kickbacks for endorsing the nongovernmental groups linked to Napoles for projects using his PDAF from 2004 to 2010.

Same results for flood mess?

This latest decision sparked public outrage and disgust online toward the country’s justice system and high officials going scot-free in corruption scandals.

Renowned screenwriter Jerry Gracio, an active commenter on social issues on X, wondered whether Filipinos should expect that certain individuals would be jailed in connection with the flood control scandal. His comments received thousands of likes and hundreds of shares.

If the country is serious about holding officials to account for corruption, Tamase said that “it is critical to actually pick up those lessons from whatever fallout there has been from the (PDAF) cases and try to see how we can strengthen institutions of accountability and processes of accountability moving forward.”

He pointed to the protracted prosecution of the Marcos family for the alleged ill-gotten wealth they had amassed during the 20-year rule of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr.

‘Unending loop’ of impunity

Professor Roland Simbulan, chair of the public policy advocacy group Center for People Empowerment in Governance (CenPeg), said that Enrile’s acquittal was a testament to the culture of impunity surrounding government malfeasance.

“It’s an unending loop which also expands into wider circles,” Simbulan said. “They are used to getting away with everything. So, just imagine that there are so many projects that we paid for and they will just run away from it.”

The long period spent in trying the charges against corrupt lawmakers and private individuals, ending in their eventual acquittal, could have been a result also of leniency by past administrations toward erring public officials.

Simbulan cited ex-President Joseph “Erap” Estrada and former first lady Imelda Marcos.

“Erap was given pardon despite being linked to the jueteng scandal. If we go a little bit farther, Imelda Marcos, who was also convicted of corruption and yet she’s scot-free,” Simbulan said. “So, it’s just impunity over and over. Remember that impunity is not just on human rights violations, but there is also impunity in corruption.”

This impunity has also resulted in Filipinos seeking justice from foreign courts.

Former President Rodrigo Duterte was charged in the International Criminal Court with crimes against humanity for his brutal drug war while victims of martial law sought relief from a Hawaii court against the Marcoses, Simbulan said.

Two key lessons

These PDAF scam acquittals should not automatically mean that there’s no hope at all, according to Tamase and Simbulan, who both emphasized that reforms were the key to bringing back the people’s trust in the justice system.

“As a teacher of law, hope is eternal,” Tamase said. “It is replenished everytime I see students who come in and who are determined to make careers that will try to resolve these pressing issues.”

It also shouldn’t stop with just hoping for a just resolution of the PDAF cases and even with the Marcos cases, Tamase said.

There are two “key lessons” that stand out, especially for the government and the court system.

Speeding up the prosecution of cases is one, he said, noting that in Enrile’s case, there was a “huge gap” between the indictment and the resolution.

“The second critical lesson is our courts should also start thinking about transparency because when a case gets to court, our default position or the court’s default position is no longer to allow publicizing the events in the case for fear of it being prejudged, or prejudicing the rights of the accused,” he said. —WITH A REPORT FROM INQUIRER RESEARCH