Project Gunita: ‘Edsa’ headlines school exhibit

Four decades have turned the newspaper pages yellow and brittle. But the message in black ink serves as a stern warning to historical revisionists, telling them to stay away—for Project Gunita is here to block them.

“We do not have the resources to fight their well-funded machinery of lies. Our main slingshot is the truth,” said Karl Patrick Suyat, 22, a cofounder of Project Gunita, a nongovernment archiving initiative launched shortly after the 2022 elections.

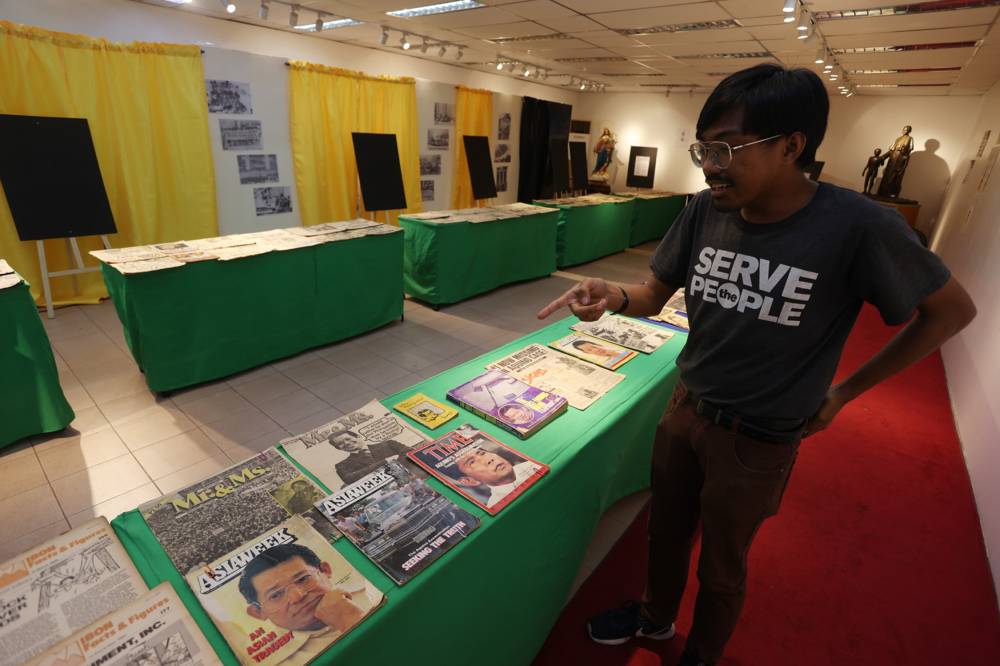

For Suyat, the truth was spread out in chronological order in a U-shaped setup at the Heritage Museum of the Don Bosco Technical Institute of Makati. The exhibit, titled “Road to Edsa,” presents a visual timeline of events that led to the ouster of the Marcos dictatorship on Feb. 25, 1986.

On display were the original front pages of the Philippine Daily Inquirer (PDI) and its sister publication, the Mr & Ms Special Edition, alongside Malaya, We Forum, Manila Times, Asiaweek, Time, Newsweek, Manila Bulletin, Philippine Signs, and handouts or leaflets from student organizations and other progressive groups.

“I would rather be shot in the Philippines than be killed by a Boston taxicab,” said a smiling image of Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. on the cover of Mr & Ms Special Edition.

Prophetic? Aquino was shot while descending the China Airlines staircase, with at least five close-in military escorts, upon arrival at what was then the Manila International Airport. The Tanodbayan (or what is now the Office of the Ombudsman) later ruled that one of the military escorts fired the fatal shot on Aug. 21, 1983.

The Aquino assassination fanned anti-Marcos sentiments and sustained mass protests that culminated in the four-day People Power Revolution.

Added contexts

“Road to Edsa,” a joint project by Project Gunita and the Don Bosco Pastoral Ministry and Institutional Affairs Office, opened on Friday with Francis “Kiko” Dee, among its honored guests. Dee is the grandson of “Ninoy” Aquino, and President Corazon Aquino, who replaced Marcos.

Visitors from other schools also came, viewing the memorabilia almost with reverence.

The old newspapers, for example, showed that as early as Feb. 19, 1986, some countries had already refused to recognize Marcos Sr.’s presidency despite his claim of victory in the snap elections held a week earlier.

Foreign magazines also featured the Philippine economic decline in late 1985, or two months before the Edsa revolt.

Downgraded occasion

All the while, Suyat gave a running annotation. “This shows that Marcos Sr. was already losing international support even before the People Power Revolution began on Feb. 22,” he explained.

The exhibit included the PDI issues on the series about the fake Marcos war medals and the Mr & Ms Special Edition reportage on Ninoy’s funeral, which the Marcos-controlled “crony” press refused to cover.

Since last year, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has downgraded Feb. 25 into a regular working day, breaking the traditional holiday observance that started in 1987.

But this year, several private schools unilaterally cancelled work and classes on Feb. 25, allowing their students to hold Mass or attend the Edsa celebration at the People Power Monument in Quezon City.

Early support

Project Gunita was conceptualized by Suyat, one of the campaigners of then Vice President Leni Robredo, Mr. Marcos’ main rival in the May 2022 presidential race.

He made the decision to start the initiative a day after the election, when Marcos was showing a clear lead over Robredo.

“If you are the President that won on a platform of disinformation and misleading the public about your own family history as a political clan, you are going to bend all means and ways to rewrite history to your favor. I thought we had to collate all materials before Marcos gets to remove them from the libraries and bookshelves,” Suyat said.

To get the project going, Suyat and his team appealed for financial support through social media. The first funds that came in allowed them to buy a scanner and a few books, including the three-volume, bound copies of Mr & Ms Special Edition. Digitizing and archiving efforts soon followed in earnest.

As they crowdsourced for more funds, an anonymous donor gave P25,000. “We were ecstatic,” Suyat recalled. More published materials were acquired, including the Agrava Fact-Finding Report on the Aquino assassination.

One supplier in Cubao, Quezon City, offered them old newspapers published from 1983 to 1986—but Suyat was skeptical at first. He checked out the trove, which included Mr & Ms Special Edition, Malaya, We Forum, Philippine Signs and others.

“Some copies were wrapped in plastic and were in good condition. The others were discolored and brittle but still readable,” he said.

When the seller learned that Project Gunita was all about preserving Edsa Revolution materials, he sold them to the group at just 30 percent of the original price.

Beyond preservation

But what else to do with such prized pages of history?

“We are not just archiving; we are also popularizing these materials by sharing them online. These are downloadable on Google Drive,” he said.

Project Gunita also has a specific target audience in mind: Students. It hopes to reach them by holding forums and exhibits (like the Don Bosco project).

“I got myself educated on martial law, Edsa and the Aquino assassination by reading the PDI,” said Suyat, who is currently taking up creative writing in Filipino at University of the Philippines Diliman. “I collected clippings of the PDI stories on Edsa, Aug. 21 and Sept. 21.”

Suyat, who was born in 2002, said his collection covered the years 2013 to 2015. He only stopped in 2016, after the death of Inquirer editor in chief Leticia J. Magsanoc, who led the Inquirer desk in planning the special commemorative stories.

Today, Project Gunita has nine members in Manila (including cofounders Suyat, Sarah Gomez and lawyer Josiah Quising) and six coordinators in Surigao, Davao, Cebu, Cavite, Ilocos Norte and Iloilo.

Broader mission

Their mission has broadened to include interviewing victims and survivors of martial law atrocities. For leads, Project Gunita revisits reports on human rights violations published in the alternative press at the time.

“We follow the stories written by Ceres Doyo,” he said, referring to the veteran journalist and longtime Inquirer columnist.

Gunita has since located a few martial law victims and interviewed some of them in Cebu. But much more needs to be done, especially in Mindanao.

“We hope to mine the Gunita archives. We can find fresh materials by interviewing the people featured,” Suyat said.

The “Road to Edsa’’ exhibit at Don Bosco runs until Monday, March 3.