Non-Moro tribes oppose proposed BARMM IP Code

DAVAO CITY—Non-Moro indigenous peoples (NMIP) in the Bangsamoro fear further marginalization, including losing their ancestral domain claims, if the current version of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao’s (BARMM) Indigenous Peoples’ Code would be approved and passed into law.

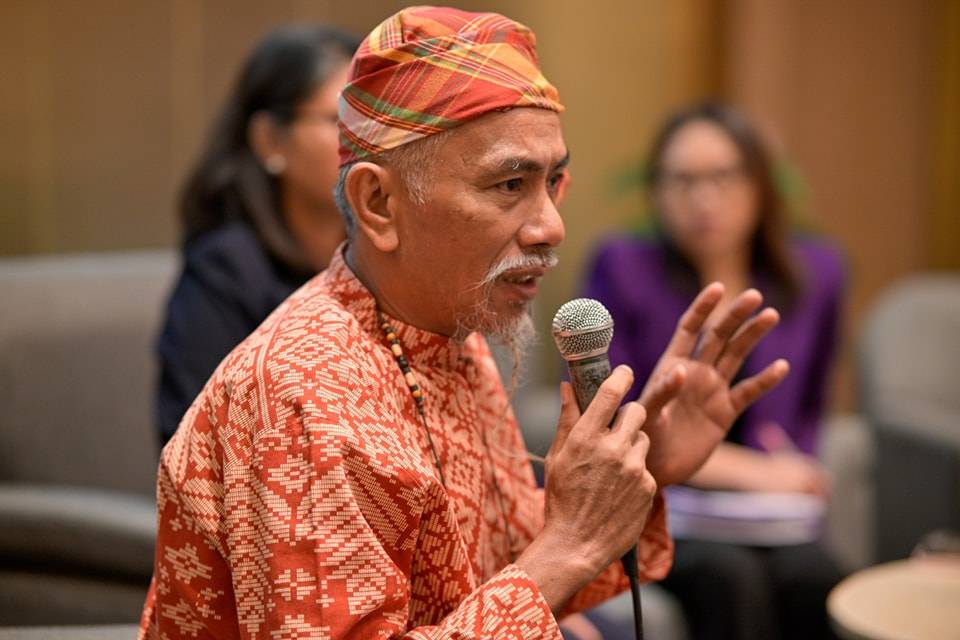

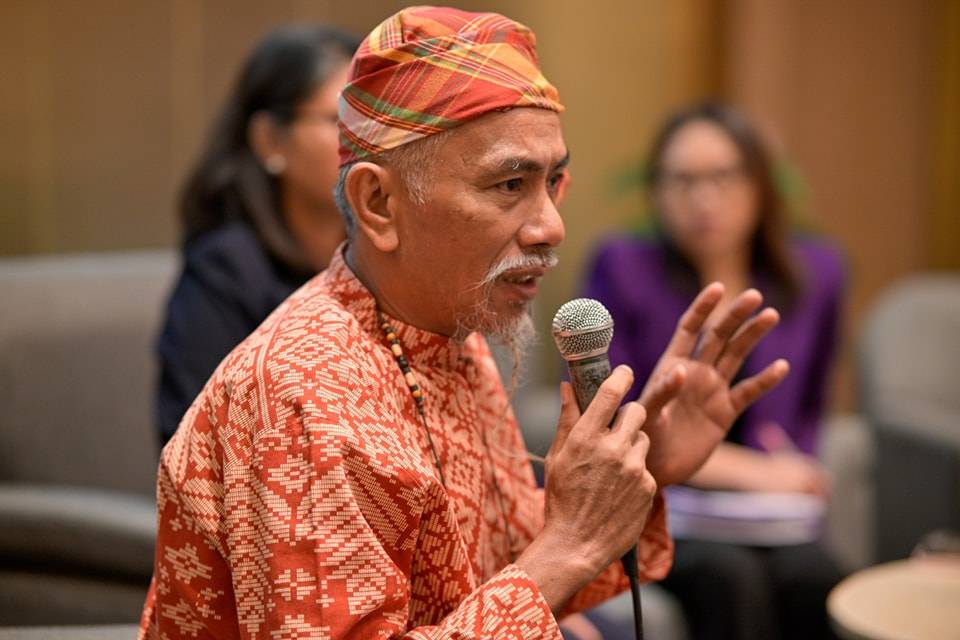

Timuay Labi Leticio Datuwata, supreme leader of the Teduray-Lambangian Timuay Justice and Governance, said that the proposed IP Code failed to recognize the NMIP, a number of distinct minority groups in the Moro-dominated BARMM.

The proposed IP Code is one of the six codes that the Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA) had been tasked to pass before the end of its term and in time for the first elections next year of the members of the BARMM Parliament.

In a position paper earlier submitted to the BTA, NMIP groups appealed that “Non-Moro Indigenous Peoples” should be included in the title of the IP Code, known as BTA Bill No. 273.

Datuwata reiterated this again in a statement on the NMIP’s “nonnegotiables” in the proposed Bangsamoro IP Code.

“We are concerned and alarmed that the proposed Bangsamoro IP Code does not recognize the distinct and unique identity of NMIPs in its provisions and framework. It weakens the rights already granted to NMIPs under the Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL) and Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act,” said a statement that Datuwata read during the May 8 forum on legal review of BTA Bill No. 273 organized by the Institute for Autonomy and Governance in Makati City.

“The BOL categorizes indigenous peoples in the BARMM as ‘non-Moro indigenous peoples’ because we are a minority within a minority group, and we have a distinct identity and struggle that we have continuously asserted,” said Datuwata.

“Non-Moro IPs will become more marginalized if they are classified as another group under ‘Indigenous Peoples’ only, and not as a distinct NMIP identity,” he added.

Among the NMIPs living in Bangsamoro areas are the Kamal, Manobo Dulangan, Teduray, Lambangian, Arumanen Manobo, Blaan and Higaonon, who dwell in ancestral lands mainly in the Maguindanao provinces; and the minority IPs on the island-provinces of Basilan, Sulu and Tawi-Tawi that included the Sama Bangingi, Jama Mapun and Sama Bajaus, among others.

Not ‘communal territory’

The group also proposed the removal of Section 3(k) of the proposed IP Code which declared Bangsamoro as a “shared ancestral domain,” because according to Datuwata, it implies that the land “has become a communal territory.”

“We will lose our ancestral domains if this Bangsamoro IP Code is passed,” he said. “It declares the Bangsamoro as a ‘shared ancestral domain,’ which implies that anyone can claim within the lands of NMIPs. We appeal that our ancestral domain title be awarded to us before the approval of any version of the Bangsamoro IP Code. We will not have the chance to continue with our delineation process nor be granted with a certificate of ancestral domain title (CADT),” he said.

He added: “Without a CADT, we have no control on which investors and development projects are introduced and implemented in our ancestral domain. We will lose our ancestral domain.”

Since 2005, or years before the creation of BARMM in 2019, the Teduray-Lambangian NMIPs already filed an application for ancestral domain title over some 208,258 hectares of land in eight towns in the then undivided Maguindanao province and in six villages of Lebak town in Sultan Kudarat province and some 14,000 ha of water.

The processing of the CADT for the Teduray and Lambangian tribe was already on its final stages when the BTA filed a resolution asking the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) to keep its hands off from the processing and granting of CADTs in Maguindanao, which had now been divided into Maguindanao del Norte and Maguindanao del Sur.

Wasted effort

According to Datuwata, efforts to claim their CADT will all go to waste if the current delineation process under NCIP will not be recognized and will be continued by the Bangsamoro’s Ministry of Indigenous Peoples’ Affairs (Mipa).

He echoed the group’s fear that their ancestral domain of more than 208,000 ha will be greatly reduced if the jurisdiction would be turned over to the Mipa under the current version of the Bangsamoro IP Code.

The NMIPs also questioned the scope of authority and powers of the Mipa, which according to them, tends to weaken and blur the distinct and unique identity of NMIPs.

The Bangsamoro IP Code grants Mipa the authority to recognize other indigenous communities, but according to the NMIP’s statement, Mipa has no legal authority to do so.