Reporting from Ground Zero of tectonic economic shifts

“Never let a good crisis go to waste.”

This is a quote widely attributed to the late British statesman Winston Churchill, referring to the post-World War II rebuilding and formation of new alliances that created the United Nations.

In the last four decades, business journalists at the Philippine Daily Inquirer have indeed looked at any crisis—whether economic or political, local, regional or global—as a clarion call to work harder, to scrutinize its causes and effects, so that policymakers, entrepreneurs and consumers can improve their decision-making.

Just as how the Inquirer had extensively covered the tumultuous events leading to the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution, we tracked all the subsequent crises that reshaped the corporate and economic landscape.

In the last 40 years, the Philippines saw four episodes of economic recession, all linked to economic and/or political crises. We had more than our fair share of scoops and award-winning special reports that influenced policymaking and market behavior.

1980s debt crisis, political turmoil

When the Inquirer was born in 1985, the country was in one such predicament.

It was the tail end of the Marcos dictatorship and the Philippines was shut off from the offshore debt market following a massive foreign borrowing binge in the 1970s.

When “behest” loans piled up, the late President Ferdinand Marcos Sr. declared bankruptcy and called for a 90-day debt moratorium in 1983.

Hundreds of banks collapsed alongside a big wave of corporate failures, the economy fell into recession for a second straight year in 1985, and investors scrambled for the exit, especially as the central bank under then Governor Jaime Laya was caught misstating the country’s foreign reserves position.

Even after the ouster of the dictatorship in 1986, the fledgling Cory Aquino administration was burdened by about $24 billion worth of foreign debt left by the toppled regime.

The central bank also incurred more than P300 billion in losses after it was made to assume the foreign debts of certain government-owned and -controlled corporations and even some private companies during the 1980s.

While none of us on the current Inquirer Business team was around at that time, tales of the mess made by the old central bank reverberated in the coming decades. The country had to create a monetary authority, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, (BSP) and completely liquidated the old central bank by 2018.

The two succeeding central bank governors after Laya, Jose “Jobo” Fernandez and Jose Cuisia Jr., firmly rejected calls for debt repudiation in the post-Marcos era to avoid becoming a pariah in the international market and to later allow the country to regain access to the global debt markets.

However, the political situation continued to be volatile due to a series of coup attempts against Aquino, the most serious of them in 1989.

Asian currency crisis of 1997

Although not as turbulent as the mid-1980s, this decade was similarly challenging as the country had just suffered a fallout from the 1990 earthquake and 1991 Mt. Pinatubo eruption. As an oil importer, it was also hit by oil price hikes when the Gulf War erupted.

These developments created pressures on government spending, leading to an economic recession in 1991.

But it was also during this decade that the Philippines finally managed to return to the global debt market after more than a decade. In early 1993, during the term of Fidel V. Ramos, the government successfully launched its maiden $150-million Eurobond issue.

The 1990s also ushered in a new leadership at Inquirer Business. In 1991, Raul Marcelo assumed the post of business editor, with the late Arleen Chipongian-Perez as assistant business editor. When Chipongian-Perez moved to Hong Kong, Corrie Narisma became assistant business editor in 1997. This writer joined the team in 1997, just when the Asian crisis was unfolding.

While doing her graduate economics studies at the University ot the Philippines Diliman, Margarita Dubuque-Gonzales, who now serves as BSP assistant governor, wrote long-form special reports that dissected the currency turmoil that began when the property bubble burst in Thailand.

For us covering the beat—during an era without chat groups and social media—physical presence was necessary to stay in the loop. Daily coverage required “stalking” monetary and fiscal officials, and doing ambush interviews of visiting bankers and other officials. When there were big developments on weekends, we would call up the residence of then BSP Governor Gabriel Singson Jr. I was in MBA school at the time but had to drop out due to the erratic schedule, where the stakeouts sometimes lasted till midnight.

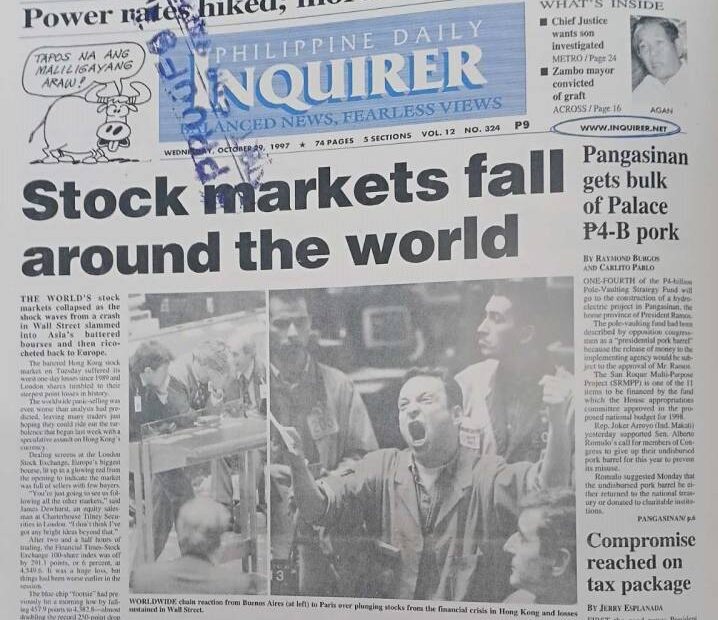

We extensively covered the impact of the crisis on the real economy. Since the devaluation of the peso on July 11, 1997, the daily grind yielded stories about the local currency hitting a new record low against the dollar, hefty increases in the BSP’s rates, banks needing liquidity support or companies seeking restructuring.

The steady peso-dollar exchange rate and preferential treatment on foreign currency deposit unit loans prior to the crisis had encouraged many companies to borrow in dollars even if their earnings were in pesos. Imagine their troubles when the peso depreciated to levels past 40:$1 from just 26:$1.

Turmoil under Erap (1998 to 2001)

The short-lived Estrada administration was another tumultuous political period that kept our business journalists busy as the shockwaves spilled over to the real economy, which was then still reeling from the Asian currency crisis.

There was an exodus of big stock brokerage houses due to a crisis of confidence, while banks and businesses dealt with off-the-chart currency volatility alongside a sustained period of high interest rates.

“Crony stocks” were the only game in town. After all, it was a period when Malacañang often influenced corporate mergers and acquisitions, as was seen during the 1999 purchase by Equitable Bank of a larger institution, PCI Bank, a deal that used the financial muscle of the Social Security System and the Government Service Insurance System.

Meanwhile, the 1999 BW stock price manipulation scandal—one that almost brought down the Philippine Stock Exchange (PSE)— likewise tagged an Estrada crony, Dante Tan. Several brokerage houses were also charged.

As regulators investigated the BW scandal, incumbent Inquirer Business Editor Tina Arceo-Dumlao, who joined this paper in 1996, was then a field reporter covering the PSE and the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The BW scandal was the last issue she covered before joining the desk. She got a lot of exclusives from corporate lawyers representing the different parties, including the scoop on the entities that would be charged with stock manipulation.

“At that time that I got the story, though, I had to weigh if I will push through with it because I just had one source—because we follow the two-source rule,” Arceo-Dumlao recalled. “But the source is reliable, so I thought I’d take the risk.”

“It was a bet, but I was confident because the (source) was involved in the investigation,” she noted.

The next day, the scoop about the result of the BW probe was Inquirer’s banner story.

“So for our story on how to cover a crisis, I can say for myself that there are times when you are faced with a decision on whether to go with your gut or not. My gut told me to go ahead and do it,” she said.

There were times when even when the story was backed by documents, we were faced with a dilemma of whether to run it and risk causing bank runs. In the aftermath of the Asian crisis, we got hold of a document listing about a dozen banks that were in a critical situation and were being closely monitored by regulators. In the end, we decided to run the story without naming the banks.

After all, one of the key lessons during the Asian crisis was that no amount of sugar-coating will make the problem go away. Our duty is to tell the story as it is and, if it’s bad, to hopefully start conversations on much-needed reforms.

Global financial crisis (2008-2009)

When two of Wall Street’s revered investment banks, Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, collapsed in 2008, the rest of the world felt the tremors. In the Philippines, leading insurance firm Philamlife had to sell some of its units as parent firm AIG restructured its global operations.

A major culprit was the heavy involvement of a number of US institutions in subprime mortgage assets that were pooled into securities, packaged nicely and aggressively sold to yield-chasing institutions across the globe. With the globalization of financial systems by this time, the crunch hit hard even the small open economies such as the Philippines.

Some of the country’s biggest financial institutions also had direct exposure to Lehman Brothers.

This paper obtained confidential documents about the seven Philippine banks with a combined exposure of $386 million to bankrupt Lehman, although the exposure constituted less than 1 percent of their total assets.

With Philippine banks hardened by the 1997 Asian crisis and the 1980s debt crisis years, however, the country weathered the new crisis relatively well and avoided a recession. We had to learn more about financial instruments that existed in other markets and understand new concepts, such as “quantitative easing.”

To counter shocks from the global financial crisis, the BSP also had to enter an aggressive dovish cycle. We covered the efforts of the national government, then under President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, to pump prime the economy.

On the heels of the global financial crisis, there was likewise more consolidation in the banking industry while weak preneed companies were unmasked.

Longest, harshest Covid-19 lockdowns

The last major crisis that devastated corporate Philippines and the broader economy was the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in massive wealth destruction and layoffs.

It was also at this time that leadership at the Inquirer Business was handed over to a new generation of editors, led by Arceo-Dumlao, while the paper started to adopt work-from-home arrangements.

It was a depressing period, but we also gave much space to businesses that stepped up to the plate and covered for the shortcomings of the government in terms of pandemic intervention.

Stories of hope, of everyday heroism, filled our pages. Big shopping mall developers, such as Ayala Land, SM Prime Holdings, Robinsons Land and Megaworld Corp., gave up billions of pesos as they waived mall rentals. We tracked the generosity of corporate Philippines as business titans forked out huge amounts to help the least fortunate.

We wrote about analysts and economists calling on the government to increase its budget for pandemic intervention, and to accelerate the rollout of vaccines. We chronicled how the crisis accelerated the digitalization of payments, benefiting fintech firms, such as GCash. It catalyzed e-commerce and the digital transformation of companies, alongside innovations in business operations.

It was during this period of Zoom meetings that a journalist’s network of sources proved to be most valuable, for the challenge was to keep getting juicy stories without leaving the house.

Another crisis of confidence

Today, the country is gripped by another crisis of confidence that has spilled over to the economy.

The public works corruption scandal has constrained government spending and gnawed on economic growth, as we have already seen in the anemic third quarter gross domestic product (GDP) growth as well as the lackluster trading in the stock market.

In the last 40 years, the Philippines has failed to wipe out, or even just reduce, corruption.

Instead it has become bigger and bolder, as if we had learned nothing from history.

Through all these, our mission remains the same. And with our army of digital natives, including a new breed of highly motivated Gen Zs who are trained to break news in real time, we strive to maintain our legacy of excellence in business and economic news reporting, all in continuing pursuit of a better future Filipinos deserve.