Safe water lifeline for Cagayan de Oro students

CAGAYAN DE ORO CITY—What began as a plan to build classrooms at Lumbia Central School here unexpectedly turned into a life-saving mission to provide clean, safe drinking water to more than 3,200 students, and inspire a continuing effort to make water available during humanitarian emergencies.

In 2024, a civic organization affiliated with the Masonic community launched an initiative to construct classrooms in underserved communities, Lumbia included.

While the building project was underway, a more urgent need emerged; the school lacked a safe and sustainable water source.

It was found that many students paid a peso per container for bottled water refills or drank from faucets that gushes water with no guarantee of potability.

“The realization struck deeply,” said Franco Catajoy, the project lead.

Catajoy added: “How could we invest in education without also addressing the basic health needs of these students? That’s when the idea took shape. What if we didn’t stop at classrooms? What if we gave them access to safe, drinkable, life-sustaining water?”

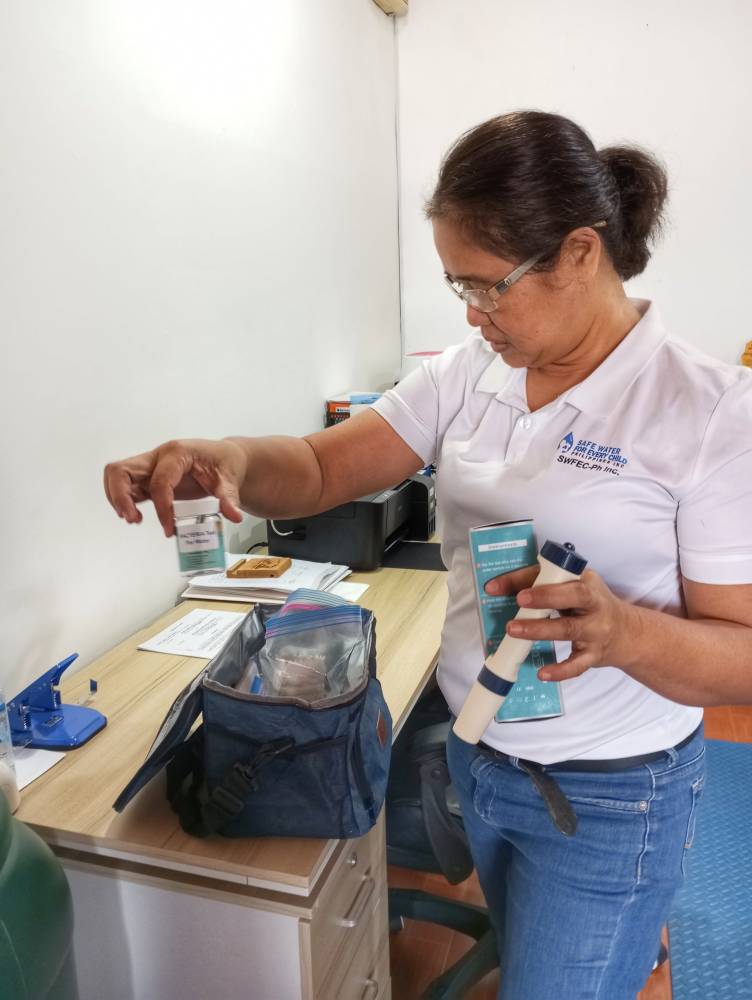

Catajoy reached out to Charlito Manlupig, volunteer chief executive officer of Safe Water for Every Child-Philippines (SWFEC-Ph), a nonprofit that installs ultrafiltration systems called SkyHydrants.

The portable system provides more than 10,000 liters of clean water per day without needing electricity or chemicals. It is a sustainable, low-maintenance solution with a lifespan of up to 10 years.

The water initiative was approved in January 2025, as an extension of the classroom project. Three months later, the school officially received the SkyHydrant system, allowing the students access to free and safe drinking water.

“This is what happens when different sectors come together with a shared purpose,” said Manlupig, adding that he was hoping schools in the country can include provision of safe water in their facility improvements.

Manlupig noted the dire statistics: about 60 million people in the country, or more than half the population, do not have safe water, and 55% of schools face the same challenge.

Saving children

Poor sanitation and contaminated water are among the leading causes of death for children under 5 years old, he lamented.

SWFEC-Ph, an infant organization composed of veteran humanitarian and development workers, wants to make a dent on this situation, especially to protect the health of children through equitable access to clean water.

In partnership with Disaster Aid Australia and the SkyJuice Foundation, it deploys SkyHydrant units to areas in need, including schools, villages and disaster zones.

At the heart of SWFEC-Ph’s mission is a deceptively simple technology: ultrafiltration units called SkyHydrants, developed by Australia’s SkyJuice Foundation. Each unit can supply safe drinking water to hundreds without electricity, filtering out bacteria and impurities.

The SkyHydrant, a portable and gravity-powered purifier is distributed globally through the SkyJuice Foundation. The lightweight, low-cost device is now central to humanitarian and development projects, emergency responses, and permanent water systems worldwide.

Simple technology

The SkyHydrant uses ultrafiltration technology—thousands of microscopic hollow-fiber membranes that filter out pathogens, bacteria, parasites and suspended solids from non-saline water sources.

Water flows through the unit under gravity or a small pressure head, passing through these fine fibers while contaminants remain trapped. The result is clear, safe water suitable for drinking and cooking.

Maintenance is simple and sustainable. Using a manual “Shake ’n Flush” cleaning process, operators rotate handles that agitate the fibers, dislodging debris and flushing it out. This process extends the filter’s lifespan for years, even under regular use.

Each SkyHydrant unit weighs about 18 kilograms and can produce 5,000 to 10,000 liters of safe water per day—enough for hundreds of people.

Because it operates without power or chemicals, the system is ideal for schools, hospitals, farms and entire communities in off-grid or disaster-affected areas.

Durability and sustainability are key. With routine manual cleaning, a single filter can last up to a decade or more before needing replacement. Aside from the initial setup, operating costs are minimal, requiring no consumables or specialized skills.

Not for sale

The system has also proven vital during crises such as the Marawi siege in 2017, the Bicol and Southern Luzon floods in 2024, and the Siargao Island power outage in 2021 that triggered a three-week water crisis.

“The inventor, Rhett Butler, is a Rotarian,” Manlupig said. “He made sure the design could be produced royalty-free for humanitarian use. That’s why we can bring it to communities for free—as long as it’s not sold.”

Rotary Clubs in the Philippines and Australia became early partners in the mission.

The organization works in close partnership with Disaster Aid Australia, led by Brian Ashworth, and the SkyJuice Foundation founded by Butler—who was recently honored with the Zayed Sustainability Prize for his contributions to global water security.

“The Rotarians were the first to believe (in the mission),” Manlupig said. “Disaster Aid Australia supplied the units, and they were among the first on the ground after (typhoon) ‘Sendong’ (in 2011).”

Building ownership

Unlike many aid efforts that fade when donors leave, SWFEC-Ph puts sustainability first.

“We don’t just drop equipment and leave. We train local people, sign agreements and even do surprise visits. If a system isn’t maintained, we take it back. Ownership is key,” explained Manlupig, who retired as top honcho of nongovernment organization Balay Mindanaw.

The model is scaling up. Last year, SWFEC-Ph was in talks for a P10-million partnership in Dinagat Islands to install units across the province’s 50 villages by 2026.

Water access is always a major concern for the island province, especially in the wake of every storm that batters it.

Manlupig recalls that the beginnings of his life in the humanitarian sector was in the aftermath of the Aug. 17, 1976 violent earthquake that struck underneath the Moro Gulf. It triggered a tsunami that killed some 8,000 people, including in Cotabato City where he was then a student.

“I simply couldn’t walk away from people still thirsty long after the floodwaters receded or after an earthquake,” he said.

******

Get real-time news updates: inqnews.net/inqviber