San Juanico Bridge: A symbol of resilience, a source of pride

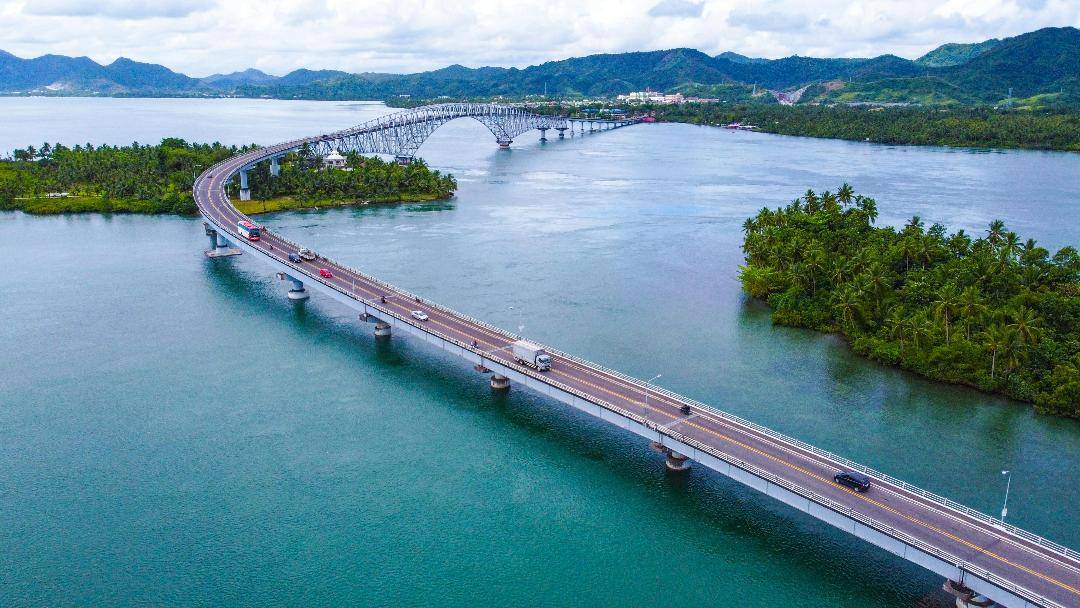

TACLOBAN CITY—For more than five decades, the San Juanico Bridge has stretched gracefully across the narrow strait dividing the islands of Leyte and Samar—a 2.16-kilometer ribbon of steel that has become far more than an engineering marvel. It is a vital economic corridor, a regional landmark, and for many in Eastern Visayas, a powerful symbol of connection, resilience and pride.

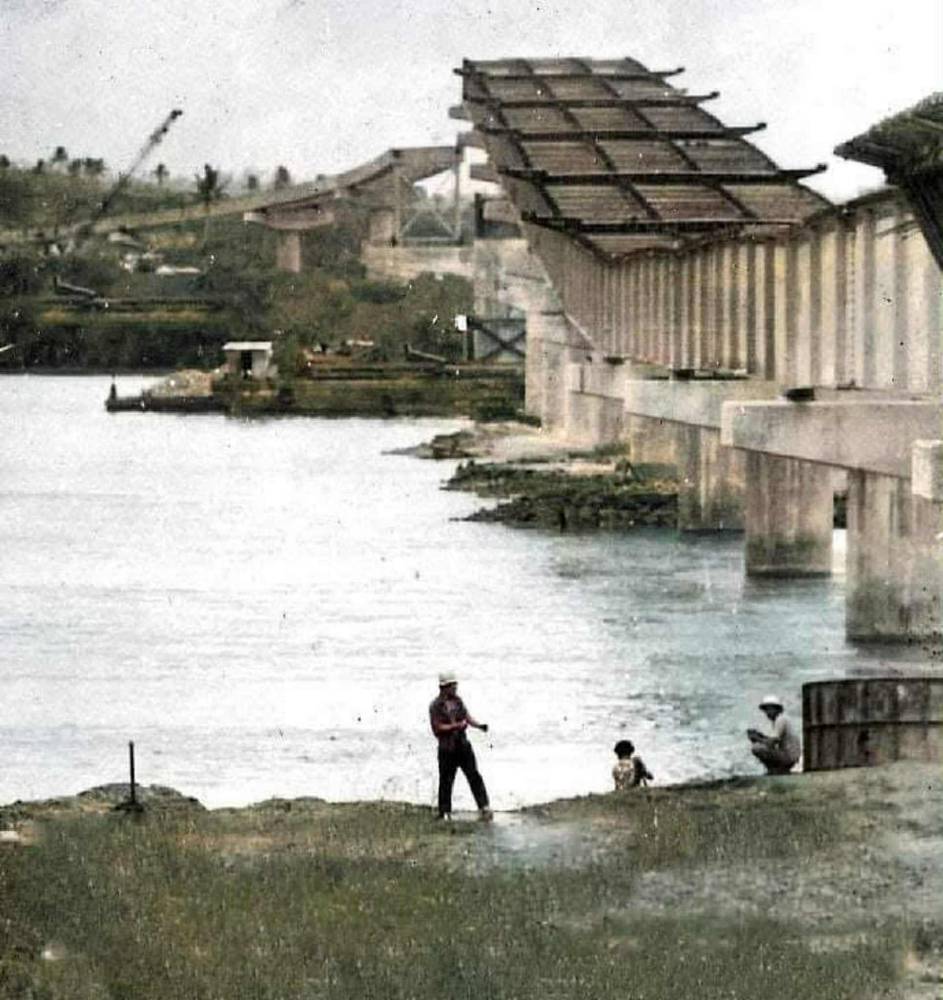

Built between 1969 and 1973 during the term of the late President Ferdinand Marcos Sr. as a ‘birthday gift’ to his wife, Imelda, who is from Leyte, and financed through Japanese war reparations, the bridge, straddling along the San Juanico Strait, said to be the narrowest in the Philippines, was once dubbed the longest in the country.

It quickly became a tangible expression of ambition—proof that even in the wake of war and division and even a major natural disaster, there was hope for rebuilding, for bridging distances both physical and emotional.

When Eastern Visayas was pummeled by Supertyphoon “Yolanda” (international name: Haiyan) in 2013, the San Juanico Bridge played a crucial logistical and symbolic role in the response and recovery efforts across the region.

Yolanda’s relief route

San Juanico Bridge served as the main land route connecting Samar and Leyte, especially Tacloban City, considered the ground zero of the world’s worst typhoon to hit inland.

With airports and seaports heavily damaged or inoperable in the immediate aftermath, the bridge, which remained structurally sound at that time, became an essential access point for relief convoys transporting food, water and medical supplies; and nongovernmental organizations and international aid organizations to reach Leyte and Samar.

Today, the bridge remains central to the region’s economy and identity.

But on May 14, 2025, that connection was disrupted. The Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) ordered restrictions on all vehicles weighing 3 tons and above after signs of structural wear—including corroded steel parts and loose bolts—were discovered during an inspection.

To keep goods and passengers moving, the government, through the DPWH and Department of Transportation, quickly repurposed an old fishing port in Barangay Amandayehan, Basey, Samar, into a docking area. From there, trucks are now ferried across the San Juanico Strait to Tacloban City.

The bridge is set for a rehabilitation costing over P800 million, but the actual repair work has yet to start, pending the release of funds by the national government.

The closure sparked concern not only for logistics and safety but also ignited a broader political and cultural discussion—one that placed the bridge at the center of a national conversation.

This was fueled by a remark from Vice President Sara Duterte, who described the San Juanico Bridge as “not a tourist attraction,” suggesting it should be valued solely for its practical use. Her statement, issued in June while she was on a visit to Australia, triggered swift responses from local leaders, cultural advocates and Eastern Visayans who have worked hard to elevate the bridge as a symbol of regional pride and tourism development.

Among the most vocal defenders was Rep. Jude Acidre of the Tingog party list, a political ally of House Speaker and Leyte Rep. Martin Romualdez. Once aligned with Duterte, the alliance has since frayed, making the Vice President’s comments all the more politically charged.

Testament of forgiveness

“For me, it’s more than just a tourist attraction,” Acidre said. “It’s more than a photo spot. The San Juanico Bridge is a powerful symbol of progress. It was built during a time when our country dared to dream big.”

Acidre went on to underscore the historical value of the structure. “Decades after World War II, two former enemies found the courage to rebuild trust. The bridge is not just steel and concrete—it’s a testament that forgiveness and partnership are possible.”

Leyte Gov. Carlos Jericho Petilla was equally quick to defend the bridge’s symbolic stature.

“If there’s a 100-km bridge in China, go there. But here in the Philippines, people come to see the San Juanico Bridge, not China,” he said, alluding to Duterte’s comparison of the structure with a 264-km bridge in China.

Evolving role

Far from just a scenic span, the bridge serves as a vital link in the Pan-Philippine Highway and enabling smoother movement of goods and people throughout the Samar-Leyte corridor. About 14,000 vehicles cross the bridge daily, with around 1,400 of them now rerouted due to weight restrictions, DPWH data showed.

Still, the push to frame San Juanico as a tourist draw has gained traction. In 2022, the Department of Tourism (DOT), along with Samar province, launched the P80-million San Juanico Bridge Aesthetic Lighting Project. With its dynamic LED displays illuminating the night sky, it quickly became a spectacle for visitors and locals alike.

DOT-Eastern Visayas Director Karina Rosa Tiopes says Duterte’s comments overlooked the evolving role of the bridge: “A tourist attraction is one particular site, a specific site wherein people go there because of aesthetic value, that they believe that, if it’s man-made, it’s an iconic structure that represents the place or tells a story of the place.”

“And in the parlance in the tourism industry, it is really accepted and known that San Juanico Bridge is indeed a tourist destination.”