Searching for Baguio’s ‘soul’

BAGUIO CITY—As the Panagbenga Hymn echoed through Session Road last week during the Baguio Flower Festival parades, students in colorful flower-themed costumes danced through city streets, evoking fond memories for visitors of the summer capital.

Social media platforms like Instagram, Facebook and TikTok were flooded with posts from frequent tourists sharing their cherished experiences at this year’s flower festival. Yet, beneath Panagbenga’s colorful displays lie deeper stories that remain largely unknown to the public—and even to Baguio’s Generation X, who, according to old-timers, must understand their history and what is worth preserving.

Mary Anne Alabanza Akers, a United States-based urban planner and dean of the College of Environmental Design at California State Polytechnic University, highlighted this in her talk on Feb. 20 at the Baguio Museum, where she discussed the search for Baguio’s “soul.”

Akers pointed out that as Filipinos commemorated the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution on Feb. 25, many remained unaware of Baguio’s critical role during that pivotal moment in Philippine history.

Akers was referring to the pivotal 24-hour period when local opposition groups and activists gathered at the Baguio Cathedral to take a stand against the Marcos regime and protect a group of defecting policemen and soldiers who sought refuge there.

When word reached Baguio that then President Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and his family fled Malacañang, the news was marked by the ringing of the cathedral’s bell—a symbolic gesture of the people’s triumph. But the identity of the bell ringer remains a mystery.

“Who rang that bell?” Akers asked. Somewhere in a family’s archive or in the distant memory of someone present that day lies the answer, she added.

“I don’t know if your memories can access that moment when martial law was declared [in 1972]. I do. Every corner of Baguio was so silent,” Akers recalled.

She went on to highlight the importance of preserving Baguio’s lesser-known narratives.

Generational gap

She pointed out that while young Filipino-Americans actively advocate for social justice issues—such as their parents’ lingering trauma from martial law and the fight for Igorot identity—there is a generational gap between their efforts and the experiences of older Filipinos who lived through these turbulent times.

To bridge this gap, Akers has returned to Baguio to collaborate with like-minded friends and Baguio old-timers to collect and document these untold stories. These narratives, she said, will be shared with younger generations through personal interactions and digital platforms.

Several local historians and civil society leaders are already contributing to this effort. Becky and Huub Luyk, long-time residents and community stalwarts, have offered decades’ worth of newspaper clippings documenting major events in Baguio and the country. Huub shared that his wife had also accumulated a mountain of journals filled with her reflections.

Journalist and book editor Nonnette Bennett mentioned the untold details captured in her editorial projects, including works for a local cooperative and the late Baguio Bishop Carlito Cenzon. Bennett also facilitated a history-writing project undertaken by 10 barangays, preserving community stories for future generations.

Meanwhile, Baguio Museum Director Estela de Guia noted that a comprehensive record of Baguio’s oldest buildings has already been compiled into a book. Several members of the academe who attended Akers’ talk pledged to make their research papers accessible online—ensuring that even the average TikTok user can engage with Baguio’s rich history.

Colonial roots

Akers reflected on Baguio’s origins, which trace back to the American colonial period. In the early 20th century, the American government established Baguio as a hill station—a cool retreat from Manila’s tropical heat—on lands already home to a thriving Ibaloy community.

“Who are the fathers of Baguio? White men. Where were the women?” Akers asked, underscoring the lack of indigenous and female voices in official historical narratives.

The city was designed in the early 1900s by Chicago architect Daniel Burnham, proponent of the City Beautiful movement, and is considered a founding father. He was commissioned by William Howard Taft, the American Governor General of the Philippines who later became president of the United States.

A multinational crew built the iconic zigzag road that opened access to the summer capital which was overseen by Col. Lyman W. V. Kennon, another founding father who was criticized in America for overspending on the mountain road that is named after him.

Many Baguio students have been taught that the names of the city’s roads and parks were named after Baguio’s American founders. But since the 1990s, schools have also taught them about the original Ibaloy settlers who were displaced when the Americans developed the city. These Ibaloy leaders and their families have been honored with city streets being named after them, like Carantes, which is Baguio’s first “living street.”

Efforts, however, to correct this “imbalance” in the city’s history are underway.

Writer Linda Grace Cariño, a former communication professor at the University of the Philippines Baguio, said Ibaloy stories are now ready to be shared, thanks to the Baguio government’s cultural mapping project, which has documented indigenous customs, artifacts and oral histories.

Akers’ family has contributed to charting the future of Baguio. She is the daughter of the late Joseph Alabanza, the city architect instrumental in developing BLISTT—a metropolitan framework encompassing Baguio City and the Benguet towns of La Trinidad, Itogon, Sablan, Tuba, and Tublay. Long before a 2019 study confirmed that Baguio’s resources had exceeded their carrying capacity, Alabanza had already advocated for low-density development to combat overpopulation, deforestation and water shortages.

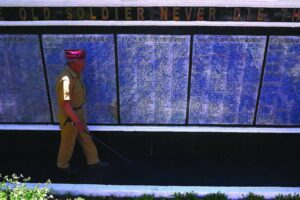

Akers stressed that reflecting on Baguio’s complex past should not fuel resentment toward colonizers or flawed leaders. Instead, she urged that these “places of memory” be viewed as “whispers of multiple histories and different social realities.”

While individual memories may seem small, she said, their collective social, economic and political impact is profound.

“Throughout the years, these places of memory and meaning made me understand —firsthand—lessons on inequality, colonialism and imperialism,” Akers said.