US record migration: Native students struggle

On a rainy Wednesday morning at Cherleroi High School, students shuffled between classes in small groups. “Hello, my Haitian friends,” one American student said as he passed Haitian girls walking in the opposite direction.

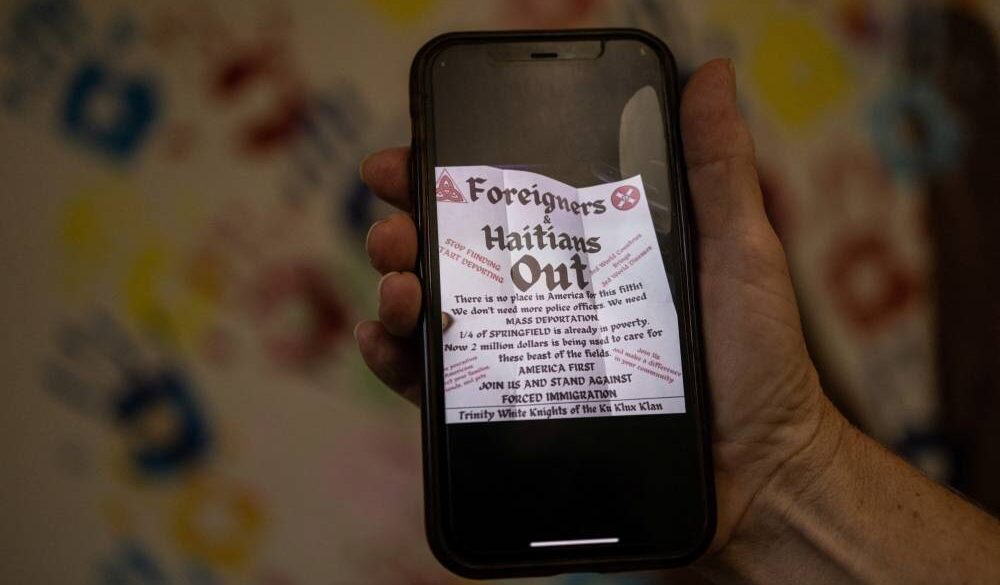

Julnise Telorge, an 18-year-old from Haiti in her final year of high school, said she feels safe in Charleroi—despite the time last school year when a white student bumped into her in the hallway and made a derogatory comment.

Telorge said the comment upset her and that she did not know why someone would say that. “I think because she doesn’t like Blacks,” she said.

School district officials said they were unaware of the incident.

The number of non-English speaking students in the 1,450-student Charleroi Area School District shot up to 220 currently from just 12 in the 2021-2022 school year, according to the district administrators. About 80 percent of those students are of Haitian descent, Supt. Ed Zelich said.

Like many of the Haitians arriving in Charleroi, the Telorge family were attracted by job openings at Fourth Street Foods, a plant packaging frozen breakfast foods located on a hill just below the school complex.

Telorge’s father, Julis, works at the plant where he earns $15 an hour, he said. He is applying for asylum.

About a third of the plant’s 1,000 workers are Haitian, according to its owner Dave Barbe, who said that there are not enough Americans in the area to do the work.

The school district has hired five new staff members, including three teachers specializing in English for nonnative speakers, as well as a part-time interpreter, Zelich, the superintendent, said.

He estimated the cost at $400,000 a year, a fraction of the district’s $30.7 million budget, but a cost the district has covered while it waits for possible reimbursement by the state.

And there are additional costs.

After parents of 37 children pulled their kids out of the school district this year to send them to the local charter school, the district was legally required to pay an additional $500,000 for transportation and the higher charter school tuition, Zelich said.

Beth Pellegrini, who attended Charleroi public schools herself as a child and served on the Parent Teacher Association, said she decided this year to send her three children to the charter school in part because teachers were too busy trying to communicate with non-English speaking students to give them enough attention.

Her 7-year-old daughter was struggling with math while her sons, who are older, have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

“My kids were all falling behind,” Pellegrini said. “It wasn’t just the immigrants, but it felt like the teachers didn’t have the time to dedicate to them.”

Joseph Gudac, the Charleroi school district business manager, said he expected the local school tax there would need to increase if the number of non-English speaking students keeps rising.

Making progress

The new dynamic in some American classrooms has challenged teachers to adapt, but it hasn’t been without strains.

In the United States, all children, regardless of their immigration status, have a right to a free public education. But the federal government pays for only a small fraction of newcomer educational services.

Smith, the Charleroi first-grade teacher, workshopped ideas with her colleagues on how to cope. She paired Haitian students with more advanced English skills with beginners, she said. She used more physical cues, pointing to get students to sit in their seats.

She incorporated repetition into her lessons, particularly around language.

Yet when the school offered to pay for teacher training, Smith did not want to take on another work assignment on top of her day job.

“That’s just one more thing that I have on my plate that I would rather not have,” she said, noting that she planned to retire in a few years. “They should be wanting to learn our language, learn our culture.”

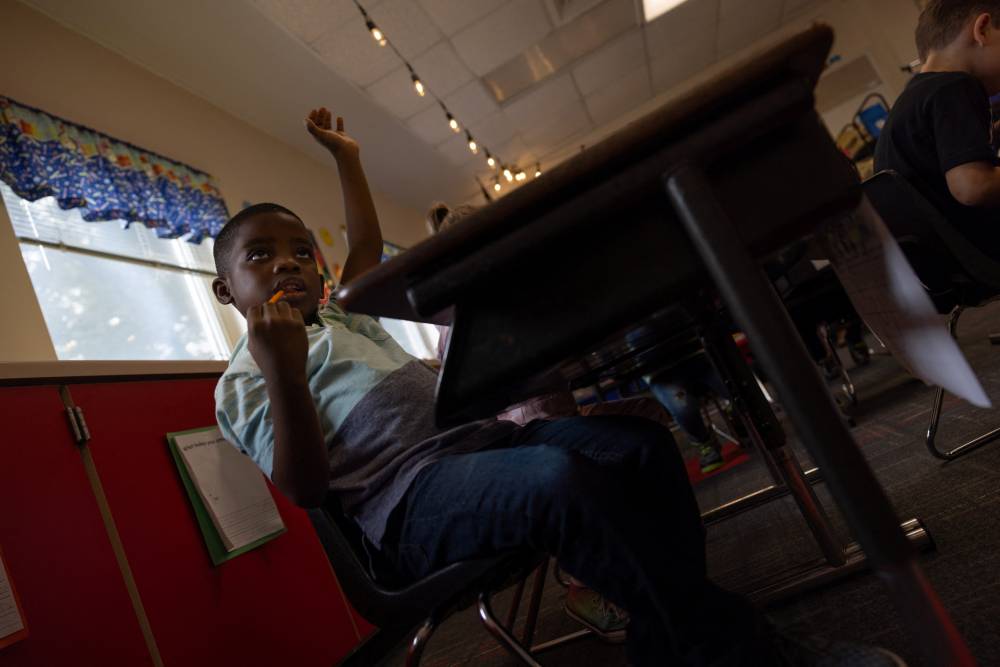

Despite the challenges, Smith said the situation has improved. While she has six English language learners out of 17 students in her classroom this year, they all attended kindergarten at the school and have a good working knowledge of the language.

During a class last month, she started the day with basics: roll call, sharpening pencils, reviewing the days of the week, and the Pledge of Allegiance to the American flag in the back corner of her colorful classroom.

The students followed the lesson and responded to cues. “They have already had a year under their belt,” she said. “So I can see that their progression has made a big difference.”

One Haitian girl in Smith’s class went from speaking no English when she entered school last year to receiving an award for academic excellence, according to Nelson, the assistant principal.

The girl’s mother died of breast cancer last year and Nelson and her husband are trying to adopt her.

“She is so resilient,” Nelson said.

Hopes for the future

When Haitian students at Charleroi’s high school need to talk to a teacher, they often go to Bridget DeFazio.

DeFazio, 40, started teaching French at the school in 2008. Her language skills suddenly became more sought after as dozens of Haitians, many of whom understood or spoke French, enrolled in the middle school and high school.

DeFazio and another teacher paid out of pocket for an ESL certification last year and she now teaches ESL classes in addition to French.

“Yeah, it has been challenging, but for me, a good challenge,” she said. “I mean, I’ve been here 17 years, so it was almost like a breath of fresh air for me, something new that I can try.”

When students walked into her ESL class last week, she greeted them in Haitian Creole.

The 10 students in her class took notes and answered questions as she ran through adjectives—smart, dumb, funny, happy, sad, shy—in a booming voice that filled the room.

“I’ve never seen kids more eager to learn,” DeFazio said. “At the end of the day, they are teenagers. They’re going to get into trouble, they’re going to be late for class, they’re going to test the limits. But when I pull them aside and talk to them, it’s, ‘OK, madame, we get it.'”

Reuters, the news and media division of Thomson Reuters, is the world’s largest multimedia news provider, reaching billions of people worldwide every day. Reuters provides business, financial, national and international news to professionals via desktop terminals, the world's media organizations, industry events and directly to consumers.