Worth the chase: A trove of scoops, special reports

Breaking a big, high-impact story ahead of everyone else is every journalist’s dream. Reporters can also earn their spurs by doing heavy spadework and delivering comprehensive, big-picture reports on facets of the Filipino condition that demand urgent government action.

Since the newspaper’s inception, Inquirer reporters and correspondents have risen to the challenge of producing pieces by which journalism careers are often measured. Some of them are agenda-setting scoops that beat the competition. Others are deep dives that went behind the scenes, connected the dots and patiently followed paper trails.

The following are some of the most historic, notable works by Inquirer journalists across four decades:

The Tasaday hoax (1987)

On Oct. 21, 1987, the Inquirer published an exclusive report that quoted Zeus Salazar, then chair of the University of the Philippines Department of History, disputing the claim of the Office of the Presidential Assistant for National Minorities, led by businessman Manuel Elizalde, that the Tasaday was an isolated and distinct ethnolinguistic tribe dating back to the Stone Age.

International scientists concluded during a conference in 1986 that the Tasaday tale was an “elaborate scientific swindle.” The Tasadays piqued the interest of experts around the world when they were first presented as an isolated tribe. Elizalde, the self-proclaimed discoverer and benefactor of the Tasadays, ran in the 1971 Senate race two months after “discovering” them.

Alih alive (1989)

The Inquirer persisted in reporting that Rizal Alih, leader of a renegade group of soldiers and policemen who figured in the Zamboanga hostage drama in January 1989, had survived, contrary to official statements that he was killed by government troops during the siege.

Those reports led to the filing of murder charges against Alih and intensified efforts to find him. It was later revealed he had assumed a new identity after fleeing to Malaysia, where he was arrested and convicted for illegal possession of firearms. He was deported to the Philippines in 2006.

The Garchitorena scam (1989)

On May 15, 1989, the Inquirer broke the story on the shady Garchitorena land deal story. It was about how the Cory Aquino administration was almost conned to the tune of P60 million through an overvaluation of a virtually barren estate in Garchitorena, Camarines Sur.

The deal was revealed to be disadvantageous to the government. The paper continued to pursue the story, with then Inquirer reporter Beth Pango and photographer Boy Cabrido hiking more than two hours on a moonless night across rugged terrain and NPA country just for the story.

In June 1989, then Agrarian Reform Secretary Philip Juico resigned from the Cabinet, saying he wanted to spare Aquino from further trouble arising from the Garchitorena land issue.

Luxury car and massager for NHA chief (1989)

It was a series of stories based on documents sent to the Inquirer by the employees union of the National Housing Authority (NHA) in January 1989. Then Inquirer reporter Fe Zamora wrote of irregularities in the agency, like the grant to then general manager Raymundo Dizon of an over-the-budget Nissan Maxima luxury car as his service vehicle and the purchase of a “momi-momi” electric massage chair “for the use of the office of General Manager.”

The reports were later confirmed by the Commission on Audit. Unable to defend himself, Dizon was made to go on leave four months later. By June, a new NHA head had been appointed.

Orbos resignation amid Cabinet feud (1991)

On July 4, 1991, the Inquirer reported about the impending resignation of then Executive Secretary Oscar Orbos, allegedly because of a campaign by other Cabinet members to discredit him after he got the highest performance rating among them in an opinion poll.

The Dolzura Cortez story (1992)

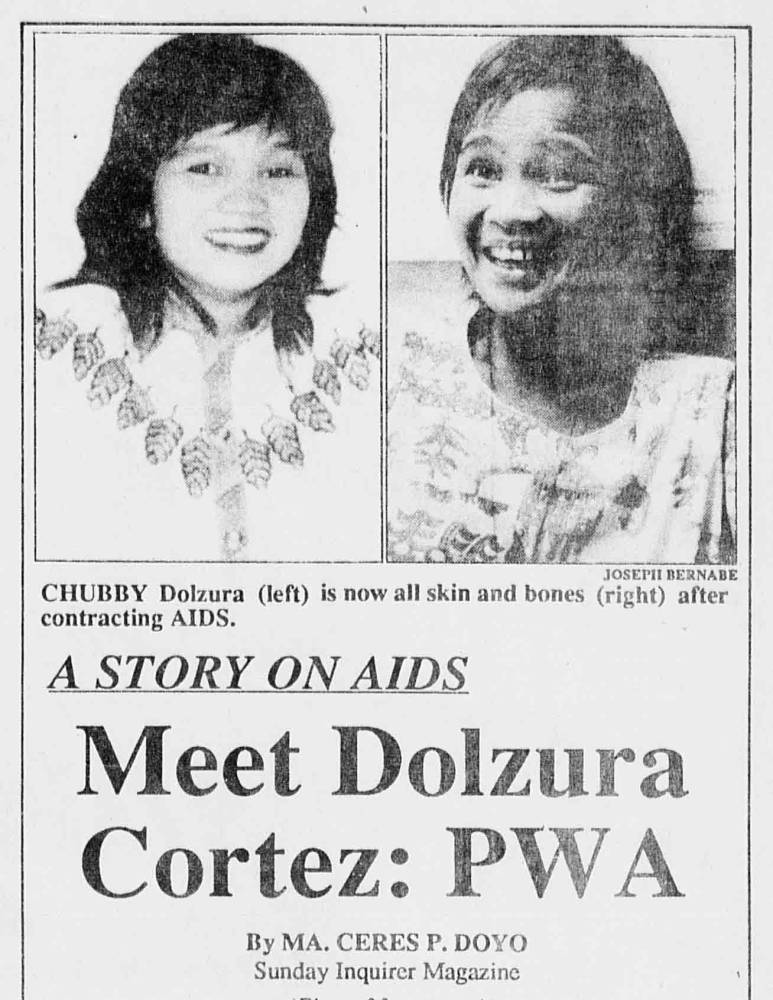

Dolzura Cortez was the first Filipino with full-blown Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) to come out and tell her story. Past interviews with Filipinos afflicted with AIDS had been on condition that no names were mentioned and no photographs were taken.

Cortez allowed not only the publication of her name but also her photograph. She also gave the Inquirer a photograph of herself before she got AIDS. Her before-and-after-AIDS pictures were revealing—they showed the readers how ravaging the disease could be.

Cortez’s story, serialized from Aug. 31 to Sept. 3, 1992, gave AIDS a Filipino “name and face.” It got tremendous response from readers and helped raise awareness of the global epidemic.

Big scandal in the Little Leagues (1992)

Shortly after the Zamboanga City Team won the Little League World Series championship, a six-part series running from Nov. 7 to 12, 1992 was published by the Inquirer, looking into their back story. Filipino pride was high then, but word was also going around that the boys were older than 12, the age limit for Little League baseball.

Digging up school and birth records, cemetery records, and interviewing neighbors and schoolmates, among others, resulted in hard evidence of name-switching, the use of imposter parents, and other details on how cheating was executed at every level of the Little League championship.

The story came at a painful price. Armand Nocum, who hailed from Zamboanga and who co-authored the series, faced death threats and was ostracized in his hometown as a traitor. He had to flee Zamboanga and ended up in Manila.

Embarrassed by the story, readers and advertisers boycotted the Inquirer, long before the Estrada-inspired boycott. The paper’s circulation and advertising dipped considerably. But after the Senate’s committee on Sports conducted hearings, the Inquirer story was confirmed. To date, with hard lessons learned, little league football has been scandal-free.

NBI move in Vizconde massacre (1995)

The Inquirer reported on June 17, 1995, that a breakthrough move will be made by the National Bureau of Investigation in the four-year-old Vizconde slay case. According to Inquirer sources, the NBI was set to file charges of multiple murder and rape against six people in connection with the 1991 massacre of the Vizcondes in Parañaque.

The Inquirer confirmed that there was a female eyewitness who said she was with the suspects, who were all high on drugs, when the crime happened. The names of the suspects were withheld, but a source described three of them as sons of a politician, a prominent businessman, and a military general.

In January 2000, the Parañaque Regional Trial Court convicted Hubert Webb, Antonio “Tonyboy” Lejano, Michael Gatchalian, Miguel Rodriguez, Peter Estrada, and Hospicio “Pyke” Fernandez and sentenced them to life imprisonment. Two other accused remained at large—Joey Filart and Artemio “Dong” Ventura. Police officer Gerardo Biong was convicted as an accessory to the crime and sentenced to 11-12 years in prison.

The Court of Appeals upheld the guilty verdict in December 2005. But in December 2010, Webb and his coaccused were acquitted by the Supreme Court and ordered released from jail.

Priest killer Manero released (2000)

On Feb. 2, 2000, the Inquirer reported on then President Joseph Estrada’s pardon of convicted priest killer Norberto Manero Jr. The report mentioned that Manero was part of the annual Christmas pardons the President gave and that he had already been out of prison since December 1999.

The reaction to the news was swift and strong. With leaders of the Catholic Church leading the outcry, many civic and nongovernmental organizations protested the pardon. So intense was public disapproval that Malacañang was forced to cancel the pardon on the basis of a technicality—Manero’s failure to report to his probation officer within the prescribed period. He was returned to the Sarangani provincial jail that same month.

To avoid a repeat of the embarrassing incident, the justice department required the publication in newspapers of general circulation of the names of convicts who have been recommended for presidential pardon, parole, or clemency.

A murder case against Manero that had been archived was also resurrected, but this case was dismissed in 2002. He was released again in January 2008.

Fire truck deal

On March 13, 2000, the Inquirer broke the news about a questionable P304.9-million government contract for the supply of fire trucks that was awarded by the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) to a company represented by two close celebrity friends of then President Estrada—Nora Aunor and Paquito Diaz. The opposition senators had a field day grilling the DILG officials involved in the project’s bidding.

The exposé also came when then Interior Secretary Ronaldo Puno was up to his neck defending himself from charges by then Sen. Miriam Defensor Santiago that he was likewise involved in the anomalous purchase of firearms and handcuffs, and the award of a drug-testing contract to an unknown company.

Several weeks later, the contract was canceled and ordered rebidded by Puno’s successor, Alfredo Lim.

The Angara diary (2001)

Edgardo Angara was the head of a panel negotiating on behalf of Estrada for a peaceful transfer of power to Arroyo at the height of Edsa 2. His diary, published as a front-page series from Feb. 4 to 6, 2001, chronicled the collapse of negotiations with the Arroyo camp during the last two days of the Estrada presidency in January 2001.

The Supreme Court then used Angara’s account to vote, 13-0, on March 2, 2001, that Arroyo was the country’s legitimate President. The diary, the court said, provided “an authoritative window on the state of mind” of Estrada. It quoted liberally from Angara’s account and used it as the basis for its conclusion that Estrada had effectively resigned from his post.

The end notes of the high court’s decision cited at least 30 stories of various dates from the Inquirer while citing the Angara diary at least 15 times, especially on the section discussing whether Estrada had resigned.

The justices also voted 9-4 that Estrada had lost his immunity from suit. Later, still using Angara’s diary as basis, it dismissed Estrada’s motion for reconsideration.

The high court decision paved the way for the filing by the Office of the Ombudsman of plunder cases against Estrada, and his arrest, trial, and eventual conviction for plunder in September 2007.

Palace payola in paper bags (2007)

In an Oct. 14, 2007, Inquirer story, then Pampanga Gov. Eddie Panlilio revealed that a Palace staff member handed him a brown paper gift bag containing P500,000 after attending a meeting in Malacañang called by then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, with around 200 officers and members of the Union of Local Authorities of the Philippines also in attendance.

An Inquirer source also said that amounts of P500,000 were given to governors, while P20,000, P30,000, P50,000, P100,000, P200,000, P300,000, and P500,000 were given to city and municipal mayors so they would support the dismissal of the impeachment complaint against Arroyo.

The report kicked up a storm and led to a Senate probe aiming to trace the real source of the bundles of cash stuffed in envelopes and brown bags.

Human bone in Bataan Camp (2008)

An Oct. 15, 2008, exclusive report said that a fact-finding team had discovered what was suspected to be a human bone in an area where Bulacan farmer Raymond Manalo said he saw people being tortured by soldiers.

Also discovered on the site were personal effects believed to have belonged to University of the Philippines student Karen Empeño and a companion, Manuel Merino, both missing by then for two years.

The findings would bolster the campaign of the mothers of the two activists who were pursuing a case against Jovito Palparan Jr. The retired Army major general was called “The Butcher” by human rights activists because of the killings of rights advocates that trailed him wherever he was assigned. An arrest warrant against Palparan was issued in 2011, but he disappeared before it could be served. He was caught in 2014.

In September 2018, Judge Alexander Tamayo of the Bulacan Regional Trial Court (RTC) sentenced Palparan and former Army Lt. Col. Felipe Anotado Jr. and former Army S/Sgt. Edgardo Osorio to reclusion perpetua—20 years and one day to 40 years in prison—for the kidnapping and serious illegal detention of University of the Philippines students Empeño and Sherlyn Cadapan in 2006.

In October 2023, Palparan was acquitted in the kidnapping case involving Manalo and his brother Reynaldo.

Cebu rapist going to Spain (2009)

On Sept. 5, 2009, the Inquirer published a story detailing the Department of Justice’s approval of the transfer of convict Francisco Juan “Paco” Larrañaga to a penal facility in Spain, to serve the remainder of his life sentence by virtue of a Philippine-Spanish agreement on the transfer of convicted persons.

Larrañaga, a Spanish citizen and scion of the Osmeña clan in Cebu, and six others had been convicted of kidnapping, illegal detention, rape, and homicide in connection with the abduction and death of sisters Jacqueline and Marijoy Chiong.

The Chiong family strongly contested the decision, but in October 2009, Larrañaga was still able to leave for Spain.

Enrile’s Christmas gift (2013)

In January 2013, the Inquirer reported that then Senate President Juan Ponce Enrile gave 22 senators a total of almost P30 million just before Christmas. The cash gift allegedly came from the funds allotted for the Senate post vacated by then President Benigno Aquino III when he won the presidential election in 2010.

Eighteen of the senators each received P1.6 million, billed as “additional maintenance and other operating expenses” (MOOE), while the other four senators with whom Enrile did not see eye to eye got only P250,000 each. They were Senators Antonio Trillanes IV, Miriam Defensor Santiago, and Pia and Alan Peter Cayetano.

On June 5, 2013, Enrile officially resigned as Senate President, saying the hate campaign against him involving the additional MOOE budget had eroded public trust in the Senate and affected the senatorial bid of his son, former Rep. Jack Enrile. The younger Enrile lost the race for a Senate seat in the May 2013 midterm elections.

Napoles and the P10-B pork scam (2013)

The Inquirer’s pork barrel exposé started with a six-part series written by former Inquirer reporter Nancy Carvajal that first came out on July 12, 2013. The series laid bare the diversion of the Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF) of senators and House members amounting to some P10 billion in 10 years, orchestrated by a syndicate led by businesswoman Janet Lim-Napoles.

Carvajal first got wind of the corruption scandal from a top agent of the National Bureau of Investigation, who was part of the task force that rescued Benhur Luy, a Napoles associate turned whistleblower. Luy eventually became the Inquirer’s top source of evidence on the pork barrel scam. The NBI agent also trusted the Inquirer to publish the story despite an ongoing NBI investigation into the allegations.

It took a village to fact-check and scrutinize the affidavits documents on the scam, and come up with the investigative report and other pork-related stories. But the resulting series rocked the nation. Public protests led to the One Million People March in Luneta, and the Supreme Court would eventually invalidate the PDAF.

Then Senators Bong Revilla, Juan Ponce Enrile, and Jinggoy Estrada were imprisoned over plunder, graft, malversation, and bribery cases filed against them at the Sandiganbayan.

In the words of the late Inquirer editor in chief Letty Jimenez Magsanoc, the pork barrel scam became “one of the biggest stories in the 28-year history of the Inquirer, next only to the Edsa People Power Revolution in 1986.”

Twelve years later, cases related to Napoles’ pork barrel scam are still being tried. Enrile, Revilla, and Estrada were acquitted of plunder, and only Estrada has remaining graft cases.

Bangladesh cyberheist (2016)

The Inquirer reported on Feb. 29, 2016, that financial regulators were investigating a money-laundering scheme that brought into the country an estimated $100 million, stolen by unknown computer hackers from Bangladesh that same month.

The series of stories that followed revealed that $81 million stolen from the New York accounts of the Bangladeshi central bank were successfully wired to a Makati branch of Rizal Commercial Banking Corp. (RCBC), then later laundered in local casinos.

The incident, considered one of the world’s biggest cyberheists, placed the country in the global spotlight.

The Senate launched a Senate inquiry on the bank heist, and the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas slapped RCBC a P1-billion fine. The bank, which claimed the money laundering was the handiwork of the “rogue” Jupiter branch then led by its manager Maia Deguito, has since then strengthened its internal controls and revamped its senior management team.

In January 2019, Deguito was convicted of eight counts of money laundering by the Makati RTC, while five other RCBC officials are still facing money laundering charges. Casinos have since then been subjected to stringent reporting obligations under the anti-money laundering law.

Bangladesh Bank has been able to retrieve only about $15 million of the money stolen, mostly from casino junket operator Kim Wong.

Tokhang for ransom? (2017)

On Jan. 8, 2017, the Inquirer published an exclusive story on the abduction of Korean businessman Jee Ick-joo in Angeles City in October 2016 by police officers. The kidnapping happened at the height of the government’s antidrug campaign, “Oplan Tokhang.”

Days after the Inquirer report, the Department of Justice (DOJ) announced its findings that Jee was strangled by policemen in his own vehicle inside Camp Crame, headquarters of the Philippine National Police, hours after he was kidnapped. His body was then cremated and the ashes flushed down a toilet at a funeral home.

Malacañang later apologized to South Korea for the murder of Jee. Cases of kidnapping for ransom and homicide were filed against the erring policemen involved in the heinous crimes, but the alleged “brains” of the abduction and murder, former police Lt. Col. Rafael Dumlao III, remains at large.

Yasay: American, Filipino, or stateless? (2017)

Documents obtained by the Inquirer showed that then Foreign Secretary Perfecto Yasay took his oath as an American citizen in 1986, contrary to his claims before the Commission on Appointments (CA) that he never acquired US citizenship.

The story, which came out on Feb. 27, 2017, was one of the biggest scoops of the Inquirer that year.

Yasay said in his CA confirmation hearing that he had applied for naturalization, but never legally acquired American citizenship. But Yasay personally appeared before Vice Consul Kristy L. Haller at the US Embassy in Manila on June 28, 2016, to formally renounce his US citizenship.

Because of the Inquirer story, the CA rejected Yasay’s nomination, ruling that he lied to them about his citizenship.

Right-of-way woes in road projects (2019)

In January 2019, the Inquirer published a three-part special report on some big-ticket projects of the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) that were suspended or not accomplished due to right-of-way problems. The special report also featured stories of landowners who had yet to receive compensation from the government. Aside from poor planning, many of the problems of the department were traced back to corruption.

The special report led to the Senate scrutinizing not only the projects of the DPWH but also the entire budget of the department. At a House inquiry, lawmakers urged officials of the DPWH and the Land Registration Authority (LRA) to purge their ranks of people responsible for pulling off irregular payments for right-of-way cases.

Some landowners reported receiving compensation after the publication of the stories. Then Public Works Secretary Mark Villar also responded that they were dealing with the right-of-way problems as fast as they could.

WellMed/PhilHealth ‘ghost’ dialysis (2019)

The Inquirer’s series on the Philippine Health Insurance Corp. (PhilHealth) fraud, first published in June 2019, resulted in a Senate probe, closer scrutiny of the organization and its officers, and the National Bureau of Investigation investigating medical centers that may have defrauded PhilHealth.

PhilHealth is believed to have lost as much as P154 billion by paying fraudulent claims from 2013 to 2018. The Inquirer also reported on the fake PhilHealth receipts used to dupe overseas Filipino workers.

The owner of WellMed Dialysis Center, a private dialysis center in Novaliches, Quezon City, accused of defrauding PhilHealth by submitting claims for dead patients, was arrested days after the Inquirer reports were published.

The WellMed case also prompted then President Rodrigo Duterte to call for the resignation of PhilHealth officials.

Sangley airport deal (2020)

An exclusive report in the Inquirer on Jan. 30, 2020, raised questions about the selection process for Sangley Point International Airport (SPIA) in Cavite. According to sources quoted in the report, a Chinese firm had seemingly been “favored from the beginning.”

The Inquirer had reviewed documents identifying the project as among those under a cooperation agreement on China’s Belt and Road Initiative signed in Manila on Nov. 20, 2018.

The project documents also indicated ongoing talks with Chinese policy banks and state-owned enterprises to finance up to 98 percent of the SPIA. The July 2019 documents identified several of these companies as CCCC, China Airport Construction Group, and China National Import and Export Technology.

The short time frame and the apparent preference for Chinese lenders discouraged other proponents from joining the bid.

In January 2021, it was reported that negotiations for the P500-billion Sangley Point International Airport were scrapped, and the award granted to state-run CCCC and taipan Lucio Tan’s MacroAsia Corp. in February 2020 would be canceled.

Quality of basic education in PH (2023)

In 2023, the Inquirer highlighted in two separate reports the studies presented by the Philippine Business for Education (PBEd) that tackled the dismal quality of basic education being received by Filipino students, and the poor training of teachers in the Philippines.

The Inquirer made use of both studies as the main banner story in print, emphasizing the urgent issues bedeviling Philippine education. These stories, one released in February 2023 and the other in May 2023, raised pressure on government leaders and stakeholders to improve the quality of learning in the country.

Seeing the flood mess—a year in advance (2024)

In October 2024, 10 months before President Marcos drew attention to top public works contractors and began inspecting allegedly anomalous flood control projects, Inquirer reporter Krixia Subingsubing had released a two-part series on the dismal state of the government’s flood control measures in Metro Manila.

The report tackled the delays and struggles in completing flood control projects. It also expounded on engineering and social solutions that agencies needed to consider for long-term flood control plans. This special report encouraged the public to pay more attention to government projects that should have long been implemented to mitigate flooding woes being experienced in the nation’s capital and across the country.

Source: Inquirer Archives