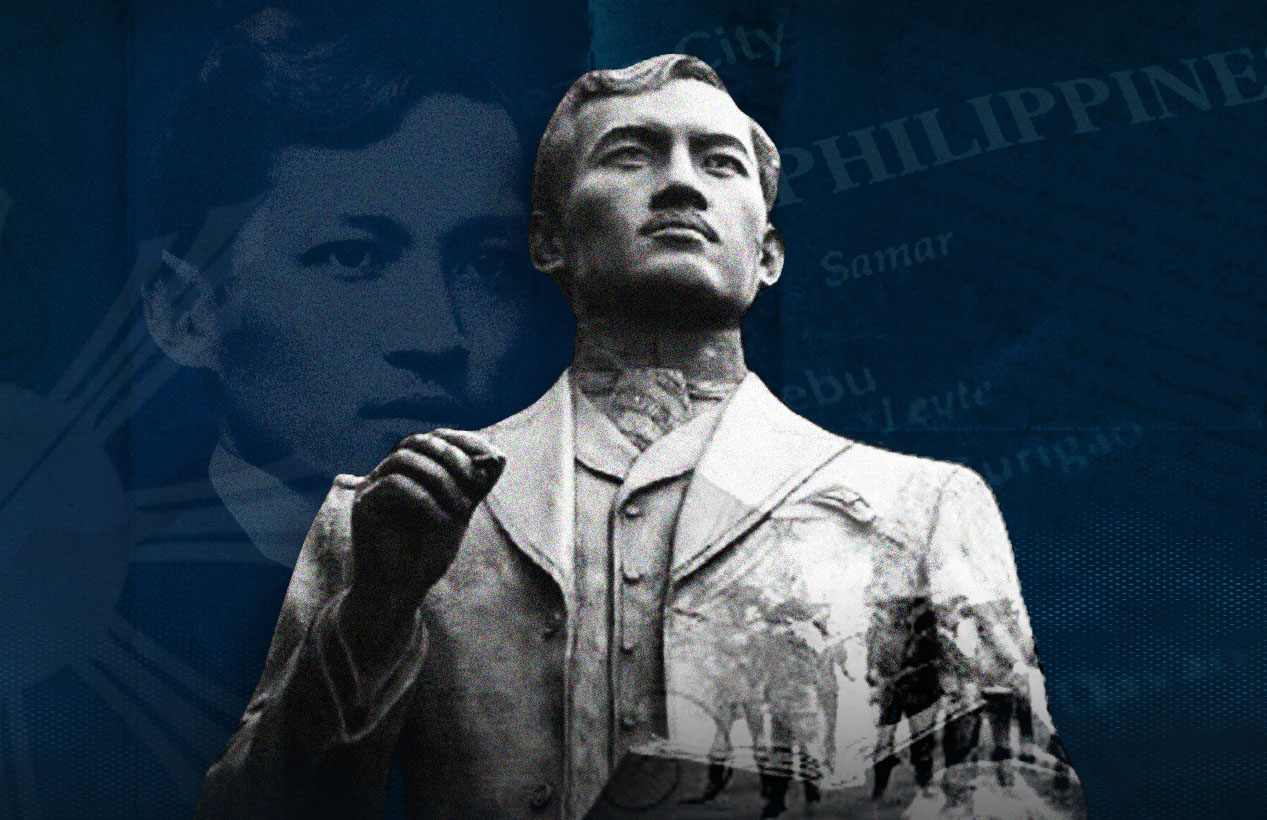

Jose Rizal: The Conservation Scientist

From my formative years, Jose Rizal happens to be a person I have always admired because the first time I learned about him was from a book my mother used to teach me how to read. Even now, 50 or so years later, I still have plenty of recollections regarding Jose Rizal I learned from that book. The story of the moth and tossing a slipper into Laguna Lake were two of his many tales I can’t forget.

In the book “Genius Intelligence: Secret Techniques and Technologies to Increase IQ” authors James Morcan and Lance Morcan described Jose Rizal as a gifted person with superior intelligence, a genius who was a polymath and a polyglot.

Ambeth Ocampo’s writing about Jose Rizal fascinated me, and I have bought his book “Rizal without the Overcoat,” a collection of his column articles. This book reveals the unknown sides of the national hero. Ocampo’s effort was to present information on him as derived from original manuscripts and books rarely touched but shelved in libraries that would capture a more human side of Rizal and not just an iconic figure.

Among the various talents of Rizal, his role as a scientist captivates me the most because I also have a keen interest in biodiversity.

Surprisingly, many people are unaware of Rizal’s prolific work as a naturalist. While in exile in Dapitan, Zamboanga, he collected numerous specimens, ultimately leading to the identification of four new species that were named after him. These include the Draco rizali (flying lizard), Rachophorus rizali (tree frog), Spathomeles rizali (fungus beetle), and Apogonia rizali (flying beetle). I find it gratifying that these species bear his name, as it clearly links Rizal to these discoveries.

The Philippines is both a mega-diverse nation and a biodiversity hotspot, which faces many challenges to its species richness. As an archipelago with more than 7,000 islands, the country provides the right conditions for speciation. Hence, the Philippines has a level of endemism (species with a limited range, thus found only in the Philippines) considered the highest in the world per unit area. It is troubling how many species might have become extinct without identification and our knowledge.

Rizal was central to the discovery of four new species mentioned. Because of dedicated individuals such as him, we now have knowledge of the rich biodiversity that this country holds. During his time, the forests were still pristine and untouched, which meant that there were likely more species out there than we have currently cataloged but were lost with the rapid fragmentation of our forests.

Rampant logging, slash-and-burn agriculture, and land conversion for livestock raising, cash crops, or housing, among others, have drastically reduced the size of our forests since Rizal’s time. According to Karol Ilagan (https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/timeline-losing-saving-philippine-forests ), lush forests once blanketed more than 90% of the country’s total land area, spanning 27.5 million hectares before colonization began.

Further, this abundant forest cover steadily declined over the years. By the end of the American rule, only 15.8 million hectares remained. This further dwindled to 10.6 million hectares just before the declaration of Martial Law in 1972. When people marched at EDSA in the so-called People Power Revolution of 1986, the forest cover was significantly diminished to just 6.4 million hectares. This substantial loss has irreparably affected biodiversity and forms the basis for how much effort one needs to put into conservation. Now, with climate change, flooding, and water shortages hitting us in the face, there is a huge realization, although quite late, of the importance of the forest, and for that reason, measures are being taken to at least protect the remaining patches.

Convention of Biological Diversity

If Jose Rizal were alive today, he would probably be actively working towards determining the most critical areas for conservation efforts referred to as key biodiversity areas (KBA). We are signatory to the Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD) agreement, which aspires to protect thirty percent of our forest and thirty percent of the surrounding seas. Using his linguistic aptitude, Jose Rizal was likely able to broker for the country’s interests or was at the forefront of drafting the new global biodiversity framework, which was passed in Montreal, Canada, in 2023. I know that among the several languages he could speak were Spanish, English, and French; Arabic and Chinese are the official languages of the United Nations.

Employing modern techniques such as DNA analysis, Rizal could have potentially compiled and precisely described hundreds of species, expanding his expertise to include marine biology alongside his already extensive array of knowledge. It is worth noting that during his exile in Dapitan, Rizal indulged in collecting and studying various specimens of fish and shells, underscoring his deep-rooted passion for the natural world.

Regrettably, Rizal’s zeal for reforms and social justice led to his untimely death. He was convicted and sentenced to death for a rebellion he never participated in but inspired by his writings. Now, his name stands for heroism and pure altruism, being a source of inspiration for many generations to come. Some, however, may unscrupulously say, “Rizal is already dead,” as a reminder that trying to follow someone like him is futile or excessively sacrificial. Yet, Rizal’s memory reminds us that true heroism is beyond the grave, living perpetually in the spirit of men and women who seek selflessly to make our world a more livable place– our conservation scientists and practitioners.

Dr. Michael P. Atrigenio is an Assistant Professor at the Marine Science Institute of the University of the Philippines Diliman and the program head of the Professional Masters in Tropical Marine Ecosystems Management Program. He is also the President of the Marine Environment and Resources Foundation.