Cleaning house without breaking the republic

The government of the day—the administration of President Marcos Jr. and Congress—is not the entire state. Its failures may expose flaws in the Constitution, but they do not necessarily undermine the viability of the constitutional state itself.

It is worth keeping this distinction in mind amid the growing calls questioning the Marcos government’s capacity to curb corruption. Even in the absence of political consensus, institutional stability can endure. In modern society, conflict is almost a ritual feature of democracy, pitting government against opposition within rules set by the Constitution—the anchor of stability from election to election.

Still, the deficiencies of governance cannot be ignored. Corruption today afflicts not just agencies involved in procurement but seems rooted in Congress and the budgetary process itself. It has seeped into the very organs meant to ensure accountability, including the Commission on Audit.

Mr. Marcos now faces a serious credibility crisis. From the evidence revealed in congressional hearings, while big-time corruption erupted during Rodrigo Duterte’s presidency, it flourished during the Marcos administration’s first three years in office. The young Marcos cannot escape responsibility for it. The kindest interpretation is that he underestimated its extent when he dared to address it in his State of the Nation Address last July. The harsher view is that he tolerated it until confronted by the sheer brazenness of ghost projects.

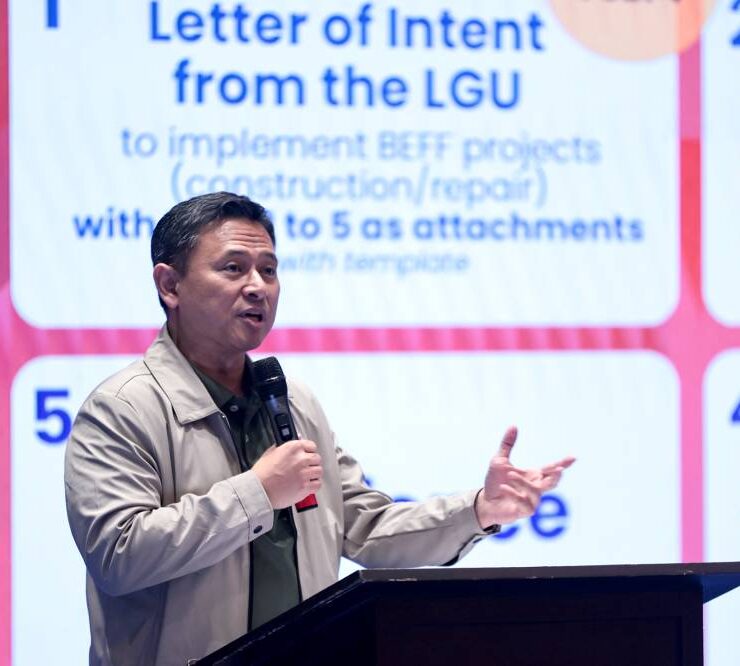

His main advantage is that he is president, able to act swiftly to stay ahead of the crisis. He began by overhauling the Department of Public Works and Highways, epicenter of the scandal, replacing the ineffectual Manuel Bonoan with the more visible and assertive Vince Dizon as secretary. He then created the Independent Commission for Infrastructure (ICI), a fact-finding body tasked to investigate corruption in public works.

The ICI has no prosecutorial powers, but its implicit purpose is to demonstrate that the government can investigate itself credibly and impartially. To do so, it must operate transparently—communicating regularly with a public weary of secrecy and conspiracies. While private hearings may be justified to protect witnesses and preserve evidence, the failure to provide prompt and regular briefings was a mistake. In the absence of clear updates, rumor and speculation fill the void. Even a brief, livestreamed media update every few days would reinforce public trust.

Another hopeful step is the appointment of a new Ombudsman—an office empowered by the Constitution to investigate and prosecute graft. Properly used, it can act on its own initiative and need not wait for formal complaints. Had it been more proactive, the ICI might have been unnecessary. Given the gravity of the scandal, speed is crucial. The quicker charges are filed, and trials commence at the Sandiganbayan, the better the chances of preserving the credibility of the constitutional order. The straight-talking former Justice Secretary Boying Remulla seems perfect for the role.

Asset recovery must also proceed without delay. The country has seen how sequestered or frozen assets quietly disappear when cases drag on. With stronger post-Edsa laws, it should now be easier to seize unexplained wealth. The government must show that corruption will no longer pay.

This reckoning began with high-profile figures, but the problem runs through every level and branch of government. The cleansing must be comprehensive. Much can still be achieved in the next two years if urgency is matched by resolve.

Yet the deeper reset can come only with the 2028 national elections. That will be the opportunity to confront the political dynasties that have long treated public office as hereditary property and government as a source of family income. These are the same clans that have corrupted the party-list system and perpetuated the politics of patronage. If the outrage now sweeping the nation is to mean anything, it must lead to their decisive defeat.

We have less than three years to turn this anger into a movement for renewal—one that reclaims the republic from those who mistake it for a cluster of fiefdoms. The process of building that movement has to begin with the self-questioning of our own everyday failures to recognize the difference between what is private and what is public, and to act ethically in conflict-of-interest situations.

—————-

public.lives@gmail.com