Counting the corrupt

The survey data relevant to corruption in the Philippines come in various frequencies. Soon after the State of the Nation Address, I cited two data sources: (a) the quarterly rating of Filipino satisfaction with the national administration in fighting corruption, done by Social Weather Stations (sws.org.ph); and (b) the annual Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) done globally by Transparency International (transparency.org).

Fighting corruption is traditionally the second-worst subject (after fighting inflation) in SWS’ quarterly report card on satisfaction with the performance of the administration. The Philippine score of only 33, on a zero-100 scale, ranks it as 114th in corruption among 180 countries, in Transparency International’s latest annual report (“Can shaming stop corruption?”, inquirer.net, 8/2/25).

Counting corrupt politicians and public officials. A third source of data is the International Social Survey Program (issp.org), which SWS joined in 1990 and in the process did 35 ISSP surveys so far. In the 2016 ISSP Role of Government survey, the respondents are asked, firstly, how many politicians, and secondly, how many public officials, are involved in corruption. The ‘how many’ is answerable by choosing from: almost none, a few, some, quite a lot, and almost all. This is how people can be asked to count the corrupt.

In Filipino, the first question is: “Sa inyong palagay, mga ilang politiko sa Pilipinas ay kasabwat sa korupsyon?” It is answerable by choosing from: halos wala, ilan, kaunti, medyo marami, and halos lahat. The second question replaces “politiko” by “pampublikong opisyal,” and has the same answer-choices.

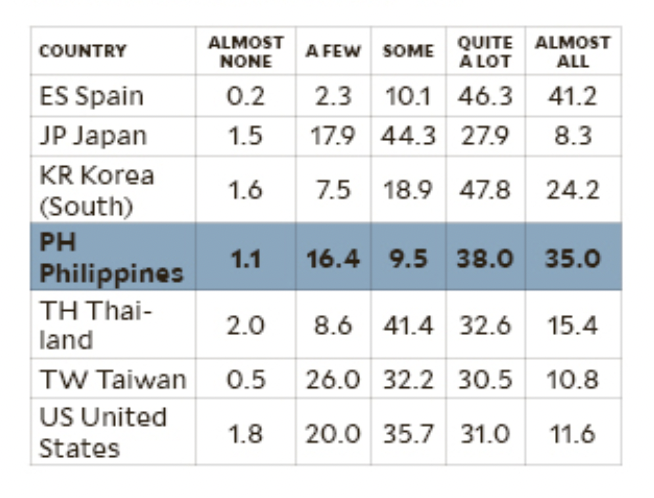

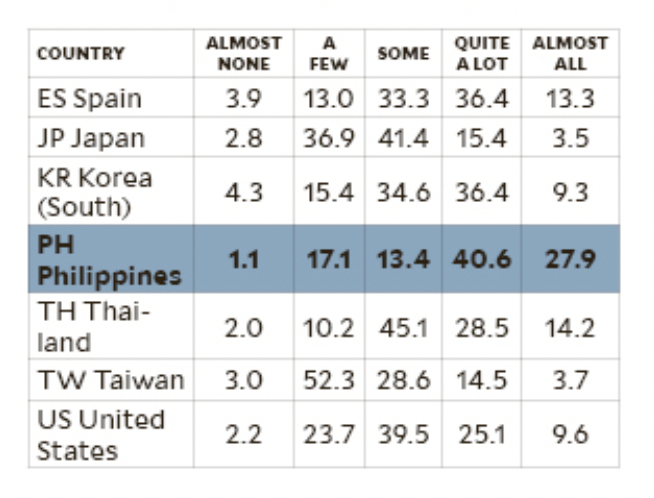

The ISSP survey results, in Tables A and B below, compare the Philippines to six other countries. They are in alphabetical order, using the international two-letter code; hence Spain is ES, for España. I included Spain and the US due to our historical connection. Japan, South Korea, Thailand and Taiwan are the only other East/Southeast Asian countries, among the 35 that did this survey. The numbers are percentages adding up to 100 horizontally, except for fractional non-answers.

Considering the most extreme answer, “almost all,” the most striking finding is in Table A, where Spain has the highest count of corrupt politicians, and the Philippines the second-highest. Then Table B shows the Philippines with the highest count of corrupt public officials, followed by Thailand and Spain. Thus, the depiction of the Philippines by the CPI as a relatively corrupt country is reinforced by the ISSP surveys.

Applying the ISSP findings to our present context, I suspect that we Filipinos are more disgruntled with corrupt senators and congresspersons than with corrupt public works engineers.

With the Philippines looking more similar to Spain than to the other Asian countries, I wonder if there is also a cultural factor operating here. There is also a large count of corrupt politicians in Chile and Venezuela, to cite other Latin countries having ISSP data. But our historical ties are closest to Mexico, which unfortunately did not do the survey (perhaps it was not yet in ISSP then?).

Our high frequency of being asked for a bribe. A third survey question in the ISSP survey was: “In the last 5 years, how often have you or a member of your family come across a public official who hinted that they wanted, or asked for, a bribe or favor in return for a service?” — answerable by: never, seldom, occasionally, quite often, and often.

Among the seven countries in the tables, the one with the highest proportion of “often” answers was the Philippines, at 6.8 percent, distantly followed by Thailand at 3.6 percent, with the other five countries all below 1.0 percent.

A. “In your opinion, how many politicians in [your country] are corrupt?” (%)

B. “In your opinion, how many public officials in [your country] are corrupt?” (%)

—————-

Source: International Social Survey Program (issp.org): national surveys of adults 18+ years old (except Japan, 16+). From ISSP Role of Government module V, fielded in 2016 (except Thailand, 2017); fielding of module VI is set for 2026.

Dr Mahar Mangahas is a multi-awarded scholar for his pioneering work in public opinion research in the Philippines and in South East Asia. He founded the now familiar entity, “Social Weather Stations” (SWS) which has been doing public opinion research since 1985 and which has become increasingly influential, nay indispensable, in the conduct of Philippine political life and policy. SWS has been serving the country and policymakers as an independent and timely source of pertinent and credible data on Philippine economic, social and political landscape.