Deadly war on drugs, again

What many thought that the war on drugs by then President Rodrigo Duterte that resulted in thousands of deaths had ended with the election of President Marcos has been proven wrong in the wake of its revival in Davao City.

In late March, Davao City Mayor Sebastian “Baste” Duterte, the son of the former president, announced the renewal of the campaign against illegal drugs in the city in light of the increase in drug dealing in his area. He said he will use the same tactics his father used when he was city mayor and later president.

Four days after that announcement, seven suspects were shot dead by Davao City police in a buy-bust operation. They reportedly fought it out with the authorities and were killed in the process.

In line with the standing operating procedure of the Philippine National Police when there are fatalities in police operations, the police officers involved in that incident were relieved from their posts and disarmed pending the investigation of the circumstances that led to the suspects’ death.

Extrajudicial meansThe Commission on Human Rights had denounced the killing of the suspects as “… these acts constitute grave violations of fundamental human rights, particularly the right to life and due process, and are in direct disregard [of] the principles of justice and the rule of law.”

“The use of extrajudicial means undermine the rule of law and destroys the public’s faith in legal systems, hindering genuine efforts to address the root causes of drug-related problems in the country.”

The reason cited by the police officers to justify the shooting of the suspects, i.e., they fought back (or nanlaban), has a familiar (and tiring) ring. It was the same excuse used in similar incidents in the past when the elder Duterte was still in office.

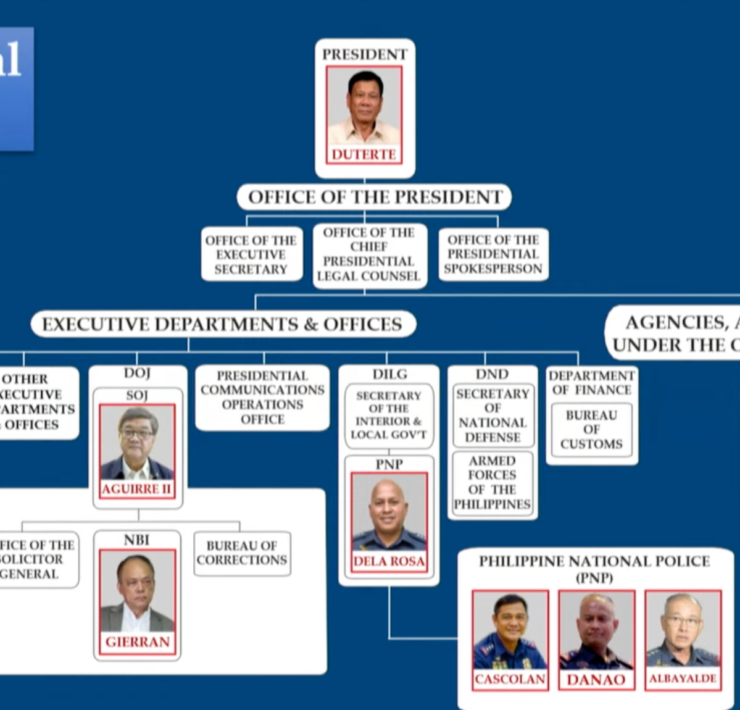

International Criminal CourtIn what looked like an uncanny coincidence, the killings happened when the International Criminal Court (ICC) is in the thick of its investigation of the death of thousands of Filipinos who were gunned down by the police during the Duterte administration for alleged involvement in illegal drugs activities.

It was as if Mayor Duterte was thumbing his nose on the ICC and publicly endorsing the strategy used by his father to stop drug addiction in the country despite its dismal failure.

The younger Duterte must have had a sense of hubris when he did that because he was in a place that, for decades, has been under the political control of his family and therefore, in his opinion, gave him “immunity” from accountability for his actions, regardless of their legal consequences.

He probably labored under the illusion that despite the end of his father’s term, the present administration would not dare question the effectiveness of the means the latter used in his war on drugs.

Besides, doesn’t Mr. Marcos owe his family a huge political debt for supporting his candidacy in 2022 by allowing her sister, now Vice President Sara Duterte, to be his running mate?

Drug dependenceMayor Duterte’s revival of his father’s mailed fist strategy differs sharply from the approach that Mr. Marcos wants to take in addressing that social problem.

In his State of the Nation address last year, he said his policy “… is now geared towards community-based treatment, rehabilitation, education, and reintegration to curb drug dependence among our affected citizenry.”

Without being blunt about it, the President was, in effect, saying that the tactics his predecessor used to end drug addiction in the country were flawed and did not accomplish their objective. Even the new chief of the PNP, Gen. Rommel Marbil, vowed that the anti-illegal drug campaign under his watch will “always go for the rule of law.”

Something must have been lost in the communication (or translation) of that message to Mayor Duterte. Or did he deliberately ignore it because it runs counter to what he had been brainwashed into believing about the drugs issue?

Unabated mayhemUnless Mayor Duterte has been living under a rock the past two years, there is a new sheriff in town who believes killing drug suspects will not minimize, much less, eliminate drug addiction in the country.

Local autonomy does not give him the right to pursue a course of action on the drug problem independent of that laid down by the national government. He cannot engage in another deadly war on drugs again under his own terms and conditions.

By his errant actions, he has given more reason for the ICC to intensify its investigation on the extrajudicial killings that happened during his father’s watch and to recommend the prosecution of the people who may have thought that the uniforms they wore gave them the license to gun down drug suspects.

Six years of unabated mayhem and disregard of human rights in the name of ending the drug problem are enough. The Marcos administration should not allow itself to be a carbon copy, by default, of its predecessor on this issue.