Education reform: Old as history

The continuing deterioration in Philippine Education is crystal clear from the Philippines’ dismal scores in the Programme for International Student Assessment. We ranked 78/78 in 2018. We improved a bit in 2022, ranking 77/81 besting Uzbekistan, Kosovo, the Dominican Republic, and Cambodia. I am surprised that there seems to be no visible urgency on this national crisis, we go on with our days afflicted by traffic, and social media feeds infested with the incoherent rambling of the old man from Davao and gossip on Kris Aquino’s new beau. We should be more invested in the state of Philippine education because it is our hope for the future.

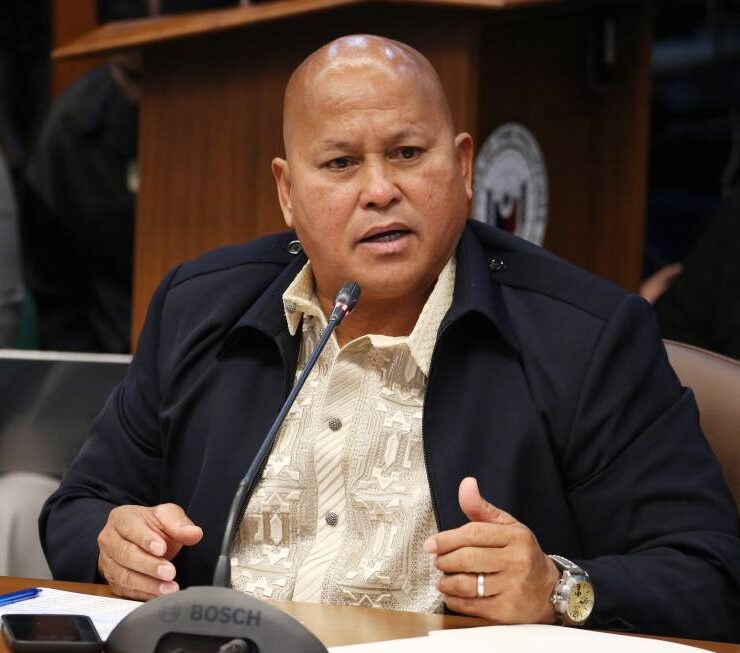

Freshly appointed Education Secretary Sonny Angara may be lucky that the shoes he needs to fill are small, but he is unfortunate that the challenges he faces are huge beyond imagination. Thank goodness he hits the ground running, armed with two road maps: the Year One Second Congressional Commission on Education (EdCom II) report (2024) and the report of the Congressional Commission on Education (EdCom I) (1991) that was chaired by his father, the late senator Edgardo J. Angara. Unlike the EdCom II report referenced in my last column, EdCom I did not indulge in self-flagellation in the face of the deteriorating state of education at the time, it moved forward with an agenda for reform. EdCom I recommended appropriate and well-considered legislation to provide structural change, it came complete with a budget and identification of potential sources of funding. It is time to re-read this now historical document from 1991 to assess how much of the reforms were actually implemented since, and whether these reforms improved things or made them worse.

Then and now, basic education lies at the heart of the crisis. In basic education, we see both problem and opportunity, the challenge is choosing the latter. EdCom I declared that the focus of all efforts should be on basic education because it failed “to teach the competence the average citizen needs to become responsible, productive, and self-fulfilling.” Two choke points in the delivery of basic education were: funding (“we are simply not investing enough in our education system”) and mismanagement (“Our education establishment is poorly managed”). Accepting budget constraints, the report declared “we must extract more efficiency and more productivity from both our education budget and our educational establishment.”

While basic education is a constitutional right, the first question was—is it universally accessible? The 1991 statistics showed that our educational system was one of the largest in the world, with one in four Filipinos in school. The Philippines even claimed 89 percent literacy in children 10 years and older. But a closer look revealed that all those rosy numbers did not apply to far-off rural areas and poor communities where drop-out rates were high and 26.8 percent of the functionally illiterate lived. In 1991, it was reported that 48 percent of elementary schools had no water, and 61 percent had no electricity! Has the situation improved? What about additions to basic utilities like stable internet connection?

Does our basic education deliver graduates who are, at the minimum, literate and numerate? Does our curriculum instruct beyond the minimum to form Filipinos: “who respect human rights, whose personal discipline is guided by spiritual and moral values, who can think critically and creatively, who can exercise responsibly his rights and duties as a citizen, whose mind is informed by science and reason, and whose nationalism is based on a knowledge of our history and cultural heritage”?

In 1991, it was already reported that only 55 percent of the competencies at each grade level were met, that six-graders only learned material equivalent to Grades 1-4. Madrasah schools were focused on Islamic instruction and Arabic, thus missing out on the basic curriculum intended for all Filipino students. Preschool and nonformal education at the time was inadequate for the population. Sometimes there were no roads to get children to school. We should ideally have elementary schools in every barangay and high schools in every town. If that can’t be met, could vouchers and subsidies herd the children into nearby private schools? It was recommended that mother tongue be used as medium of instruction in the elementary grades shifting to Filipino with English studied as a foreign language from Grade 3 to high school.

The current debate on the school calendar is not new. In 1991, the recommendation was to increase school calendar days from 185 to 200 and “granting provincial superintendents the authority to determine the beginning and end of the school year, taking into account the peculiar circumstances of each community.” Today, much remains centralized in Department of Education-Manila.

Solutions to many of our educational problems are as old as history. Before 1991, reforms were recommended in the 1925 Monroe Survey on Philippine education and the 1863 decree on educational reform. Reading and comprehension is not just for basic education students but for today’s policymakers who need to look back to move forward.

Ambeth is a Public Historian whose research covers 19th century Philippines: its art, culture, and the people who figure in the birth of the nation. Professor and former Chair, Department of History, Ateneo de Manila University, he writes a widely-read editorial page column for the Philippine Daily Inquirer, and has published over 30 books—the most recent being: Martial Law: Looking Back 15 (Anvil, 2021) and Yaman: History and Heritage in Philippine Money (Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, 2021).