Electing a pope

A social media exchange on the outcome of the recent papal conclave caught my attention the other day. It went like this:

A: “Sayang, hindi Filipino ang napiling susunod na Santo Papa! (Too bad, a Filipino wasn’t chosen to be the next pope.)”

B: “‘Te, hindi ito Miss Universe, at hindi ikaw ang Holy Spirit! (Sister, this is not the Miss Universe pageant, and you’re not the Holy Spirit!)”

As amusing as this online conversation was, it touches on familiar sentiments many of us can easily relate to.

The impulse to root for someone we know—or someone who resembles us—is deeply human. We take pride when one of our own gains prominence on the national or world stage, whether in sports, science, the arts, politics, or religion. It’s as if their achievement becomes our collective triumph. Conversely, when our favored candidate doesn’t make it, we often search for explanations. Sometimes, these turn into sweeping judgments, attributing the loss not just to the individual’s shortcomings but to a perceived inadequacy in our own people or culture.

At times, we even cry foul. Drawing from experiences in other domains, we begin to suspect that our candidate was probably outmaneuvered, or worse, that the process was rigged. Such suspicions—of bias, favoritism, or exclusion—typically haunt, in particular, those involving international contests. Racial or regional prejudice is a common suspect.

In the case of papal elections, Catholics are told to trust in the guidance of the Holy Spirit. One can assume that this invocation carries deep meaning for the cardinal-electors. But being human, they are not immune to influences shaped by their backgrounds—national, cultural, or ideological. Some might believe, for instance, that the election of Cardinal Robert Francis Prevost, a United States-born prelate, was less about divine inspiration and more about realpolitik: that, in a time of global instability, the Church needs someone from the world’s most powerful nation.

Personally, I believe the opposite may have been true. That, despite his closeness to the well-loved Pope Francis, what might have worked against Prevost’s chances was precisely his American origin—the inescapable shadow of the world’s most imperial nation. His choice to speak in Italian and Spanish, not English, during his first public appearance from the balcony as Pope Leo XIV, tells a lot. It signals a wish to be seen not as a representative of the United States, but as the leader of a Church seeking humble, global engagement. (Prevost spent much of his religious life as an Augustinian missionary in Latin America and even took Peruvian citizenship upon becoming bishop of the coastal city of Chiclayo.)

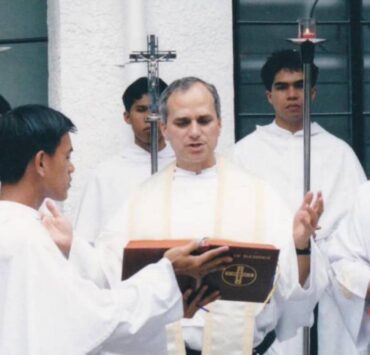

Because my brother, Cardinal Pablo Virgilio David of Kalookan, was one of the 133 cardinal-electors in the conclave, I followed the events leading up to it with keen interest. Still, not wanting to place him in a compromised position, I refrained from asking how the pre-conclave meetings—known as general congregations—were unfolding. Instead, I relied on regular updates from Zenit News, the Rome-based online magazine.

From these reports, I gathered that the pre-conclave discussions and informal conversations revolved around three clusters of questions: First, what is the current situation of the world? What are the urgent needs and signs of the times? Second, how is the Church responding to these realities? How does it understand its mission in an evolving world society? And third, what kind of leadership does the Church need now? Should the new pope emphasize strict fidelity to doctrine, or embrace a bolder engagement with the modern world, marked by openness to change?

From what I read—and from what I heard at the recent press briefing at the Pontificio Collegio Filippino in Rome, led by Cardinals Luis Antonio Tagle, Jose Advincula, and David—it seems these general congregations became enlightening moments for all in attendance. Any cardinal could speak; and many did, offering candid insights into their concerns and hopes. Some of these interventions, like the one by 93-year-old Cardinal Zen of Hong Kong, found their way into the press. Most, however, were intended only for the electors themselves. I read that Cardinal Ambo’s contribution left an impression. But out of fraternal respect, I have not asked him what he said.

One wishes we took our own national elections as seriously. That is, with the same degree of conscientiousness, reflection, and shared sense of mission—proceeding from an honest appraisal of where our country stands, where it’s headed, and what kind of leaders the times demand. Especially now, as we head into the midterms, we might learn something from a gathering of elderly men in red robes who, for a few solemn days in Rome, sought to read the signs of the times before casting their vote for the future.

—————-

public.lives@gmail.com

Anchoring UHC for the next generation