IPs’ seat at the table

For generations, indigenous Filipinos have fought for a seat at the table where discussions are made on the policies that affect their communities and shape their lives.

The Supreme Court’s decision to side with Aeta leader Chito Balintay, who was previously disqualified by the Commission on Elections (Comelec) from running for governor of Zambales province on a technicality, is a step toward breaking this cycle of exclusion that has kept indigenous peoples (IPs) from public office for too long.

By ruling that Comelec’s disqualification of Balintay was unjustified, the high court reaffirmed that election rules are not supposed to serve as tools of disenfranchisement, especially for marginalized sectors and minority groups. Certainly, this ruling does not guarantee victory for Balintay at the polls, but it ensures, at the very least, that Zambales voters are the ones who shall decide his fate, rather than a mere bureaucratic hurdle.

That alone is a win for indigenous representation.

Late by only three minutes

During its full-court session last week, the high court found that the Comelec committed grave abuse of discretion in barring Balintay from filing his certificate of candidacy (COC), because he was late in submitting the complete requirements—by three minutes.

Balintay filed his COC on the last day of filing in October last year, just 25 minutes before the 5 p.m. deadline, but it turned out his application lacked a required fifth copy and documentary stamps. He rushed to complete the requirements, but by the time he came back, the deadline had already lapsed.

Under Section 37 of Comelec Resolution No. 11045, incomplete COCs shall not be accepted even if submitted on time. The poll body invoked this rule in disqualifying Balintay from challenging the incumbent Gov. Hermogenes Ebdane Jr., who is seeking his third and final term, in the May elections.

Based on a Supreme Court press briefer explaining its decision, the justices chastised the Comelec for its inflexible application of its own rules even when those same rules might no longer serve the interest of justice and fair play.

Elections are “not conducted under laboratory conditions,” the tribunal reminded the Comelec, adding that it should be able to make quick decisions in response to unforeseen circumstances that could “undermine or subvert the will of the voters.”

“Given these considerations, along with Balintay’s unique circumstances, the SC found that the Comelec’s strict application of its rules was unjustified, warranting the reversal of its decision,” the briefer said.

‘Democracy’ at work

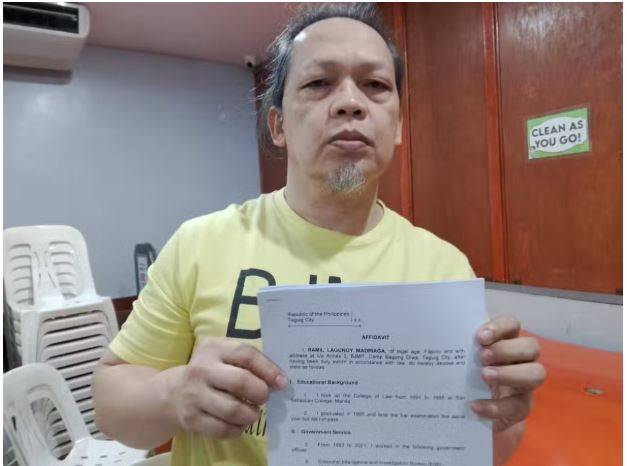

On the day the decision was announced, Balintay expressed his elation: “I am happy because I felt democracy [at work] through the Supreme Court’s support for me when it was just a temporary restraining order, and it is even more strengthened now.”

The Indigenous Peoples Rights Act of 1997 provides that “the State shall take measures, with the participation of the ICCs (indigenous cultural communities)/IPs concerned, to protect their rights and guarantee respect for their cultural integrity, and to ensure that members of the ICCs/IPs benefit on an equal footing from the rights and opportunities which national laws and regulations grant to other members of the population.”

Not expressly stated, but implied, is the right of IPs to participate in local or national governance.

In his case, Balintay is not an outsider to the bureaucracy in his home province. He served as an ex-officio board member of the Zambales provincial board and was the first provincial officer of the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples. He also represented the country’s IPs at several United Nations conferences in Geneva, Switzerland.

True democratic participation

Still, Balintay’s candidacy challenges the notion that governance is reserved for the well-funded and well-connected. It is also a fitting reminder that the struggle for indigenous representation is not just about the recognition of their culture and traditions but about ensuring that their communities have a say on policies affecting their lands and rights.

The Supreme Court ruling should not, however, be the end of the discussion. It should spark a wider conversation about the participation of indigenous peoples in mainstream politics and the systemic barriers that keep them in the fringes of society. How many other indigenous peoples like Balintay have been discouraged from leadership roles in public office as a result of these impediments?

True democratic participation means removing obstacles for those who have historically been sidelined in traditional politics. This is by no means an endorsement of Balintay, but a celebration of the chance afforded him to campaign and to present his platform to the people of Zambales. Regardless of the outcome of the election, the mere fact that an IP leader’s name will be on the ballot is in itself a breakthrough for a more inclusive democracy.