Learning from Vietnam

The battered Department of Education (DepEd) got another black eye last week following Sen. Sherwin Gatchalian’s revelation that a little over half of the P13.69 billion allocated for the senior high school voucher program (SHS-VP) did not go to the poor students for whom it was intended, instead going to those whose families could afford their education, resulting in “wastage and leakage” of government funds.

Introduced in 2015, the SHS-VP was designed primarily to help the poor and marginalized senior high school and at the same time address overcrowding in public schools by using the voucher—with the value ranging from P14,000 to P22,500—to enroll in participating private schools.

But as Gatchalian’s office found out, in school year 2019-2020, P7.3 billion or 39 percent of the P18.76-billion fund set aside for the educational assistance program did not go to poor students. It was even worse in school year 2021-2022 when 53 percent of the P13.69-billion allocation went to those who should not have qualified for the program.

Serious shortcomings

Given this trend, one could reasonably conclude that in the succeeding years, the share of nonpoor students enjoying the benefits that are not meant for them would likely be even higher, causing Gatchalian to sound the alarm.

“We need to correct this immediately,” said Gatchalian, chair of the Senate committee on basic education.

This is not just an issue of being “efficient,” however, but a case of injustice as the poor who need the assistance the most are not getting what are due them to improve their chances of having a better life through education, which is deemed a right and not a privilege in the Philippines.

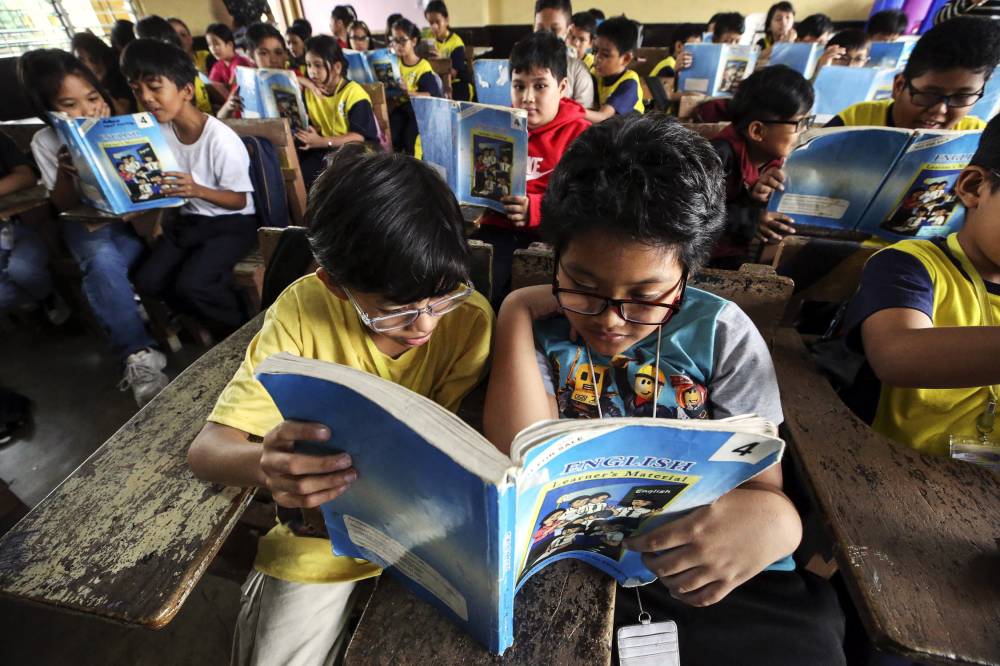

It was not the first time that DepEd had been called out for its serious shortcomings in implementing programs meant for the poor. The Commission on Audit had noted back in 2018 that DepEd had been granting subsidies to those who did not need them. Recently, Gatchalian also took DepEd to task for managing to procure only 27 textbook titles out of the 90 required for Grades 1 to 10 since the K-12 curriculum was introduced in 2013.

Litany of problems

Indeed, only learners in Grades 5 and 6 have all the textbooks they need for all of their subjects, according to the Second Congressional Commission on Education (EdCom II) in its Year One report, prompting Gatchalian to file a resolution seeking an inquiry into this latest addition to the DepEd’s litany of problems that have combined to pull down the quality of public school education in the Philippines.

The gravity of what ails the education sector is reflected in the Philippines being among the worst performers in the 2022 Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) among 81 participating countries, which indicates that our students today are ill-prepared and ill-equipped to compete in the real world.

Learn from Vietnam

In stark contrast, students in nearby Vietnam scored close to the average among the advanced countries that form the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, with its government committing time and resources for the students to score even higher in the next ranking cycle.

EdCom II went to Vietnam last week to learn from its success in the education sector, showing just how bad our education system had become that we need to learn urgently from our neighbors.

“We want to learn from Vietnam because its stage of economic development and level of education spending are not far from ours, and yet their learners are way ahead of ours,” said Gatchalian, who co-chairs EdCom II.

EdCom noted that Vietnam’s average Pisa score (468) was way above the Philippines’ (353), and this despite the former spending about the same amount in education as a share of gross domestic product, at 4.06 percent compared to the Philippines’ 3.6 percent.

Government’s top priority

By absorbing Vietnam’s best practices, the hope is that these government officials would be able to influence policies and craft reforms to dramatically improve the level of basic education in the Philippines.

But our policymakers and DepEd officials should not wait for the EdCom contingent to bring home Vietnam’s lessons. They should perform the very basic requirements, which is to ensure, for example, that the program meant for the poor will actually help the poor, and that money already set aside for the DepEd’s programs will be religiously and efficiently spent to achieve the intended results.

All administrations have said that improving education is the government’s top priority, thus the sector usually gets the highest allocation in the annual budget. The 2024 budget of P5.768 trillion is no different, with the education sector allotted the biggest share of P924.7 billion, an increase from 2023’s P676.1 billion.

The challenge therefore is to make sure that every single peso will go to the right programs and to the right beneficiaries. Hopefully, our DepEd officials need not to go to Vietnam to learn how to do this.