Numbers that hardly matter

My research, as a social scientist on the subject of human well-being and the quality of life, has been highly involved with numbers. I think all aspects of life are measurable, and can be fitted with numbers, properly designed. But some numbers currently used to indicate the state of human well-being are poorly fitted for the task, and thus hardly matter to me.

The prime poorly-fitted number is the Gross National Product, including its growth rate. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals were adopted, in 2015, precisely to take the place of GNP as a development tracker. There was a recent slowdown of Philippine GNP, but it should not worry us. GNP is the aggregate value of what Filipinos produce; a growth of 5, 4, 3, or even 2 percent per year is more than enough to match our population growth of 1 percent per year (see “What for, GNP?” 10/11/25).

The GNP is not manageable by any institution in particular, mind you. It is the result of combined public and private efforts, including that of individuals. The government itself is directly responsible only for its own share of GNP, much of which is instrumental, i.e., for keeping internal peace, providing national security, and paying the bureaucracy, all of which are already counted in the value of private production that they make possible.

Only part of the government’s contribution to GNP is directly beneficial to the people. It has programs that directly fend off hunger and poverty among people at present, and protect the environment for the sake of people in the future. These all deserve separate numbers, many of which are being generated by surveys. (The loss of government funds to corruption is pure waste, of course).

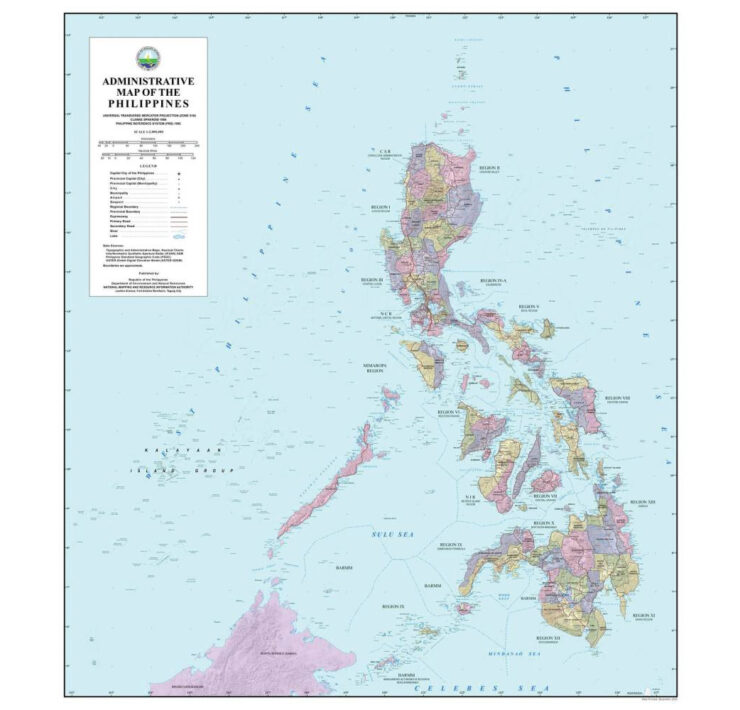

A cross-country comparison should not matter if it only promotes envy. One often hears it said that South Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam have “overtaken” the Philippines in terms of indicators like GNP per capita, internet speed, or public transport efficiency. Yet we Filipinos are not intrinsically worse off as soon as our neighbors become better off.

Do those who imply that it was authoritarianism that impelled other countries to overtake us, also consider what we Filipinos have achieved in terms of democracy (“Numbers about democracy,” 8/16/25)? Can they compare, like we can, the numbers of people that got better off and got worse off from the past, or the numbers optimistic and pessimistic about the future (see “How many Filipinos progress?,”9/6/25 and “No lack of optimism now,” 9/27/25)? A neighbor’s success is not inherently one’s failure; nor does one’s success signify a neighbor’s failure. We in Association of Southeast Asian Nations should examine each other’s numbers more closely, and learn from them.

Another number that is only peripheral to Filipino well-being is the exchange rate between the Philippine peso, and the US dollar. One currency is the means of buying our products; the other is the means of buying American products. An increase in the peso cost of a dollar does not, ipso facto, make us worse off; neither does a fall in it make us better off. Some of us are net buyers, some are net sellers, and still others are both buyers and sellers, of US dollars.

Movement in the peso-dollar exchange rate is affected by price inflation in the Philippines relative to the United States (US), which happens to be favorable to us at the moment. Our own annual inflation has recently been around 2 percent, whereas that in the United States is already 3 percent (see “Inflation edged higher in September, as tariffs raise some prices,” https://www.nytimes.com, 10/24/25).

Historically speaking, our current inflation is on the low side–which is also favorable vis-à-vis poverty and hunger–while the current US inflation is on the high side. The Trump administration’s misunderstanding of tariffs as taxes on sellers, rather than on buyers, works against the interest of American consumers in general and gives the dollar a tendency to depreciate against all other currencies.

Finally, the index of stock prices in the Philippine exchange is often cited by business pundits as a measure of economic health. Many are bewailing the drop in the stock price index this year. But the index directly concerns only those who own tradable stocks or have invested in mutual funds with a cash-in value. Such persons are very few among Filipinos–unlike Americans, a majority of whom own stocks (usually through their retirement accounts). In either country, the great bulk of such owners are in the topmost income classes.

—————-

Contact: mahar.mangahas@sws.org.ph.

Dr Mahar Mangahas is a multi-awarded scholar for his pioneering work in public opinion research in the Philippines and in South East Asia. He founded the now familiar entity, “Social Weather Stations” (SWS) which has been doing public opinion research since 1985 and which has become increasingly influential, nay indispensable, in the conduct of Philippine political life and policy. SWS has been serving the country and policymakers as an independent and timely source of pertinent and credible data on Philippine economic, social and political landscape.

Individual rights to one’s image